A couple of news stories centered on Montana caught my attention this past week. The Missoulian ran a series of well-reported stories on the state’s foster care system, Addicted and Expecting: How Montana’s Lack of Resources Impacts Mothers and their Children. Montana, a state that is struggling like many others with the opioid crisis, has become the “child removal capital of the United States.” This at a time when research on best practices suggests that adequately funded and accessible drug treatment programs for troubled parents produces better outcomes than placing their children in a foster care system characterized by neglect, abuse, and poor conditions.

The history of state foster care systems and Native American children is a distressing one, and the problems continue, most notoriously in South Dakota. Steven Pevar, whose ACLU handbook I use in my American Indian Law course, has written extensively about the problem. In Native America, I write about this history, and the events that led to the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978. It is a subject that catches the attention of my students, and I have written on this blog about continued assaults from the political right on the ICWA.

The Missoulian devoted one article in the series to conditions on reservations where drug treatment programs are in especially short supply. The figures presented by Lucy Tompkins, who reported this piece for the paper, are staggering. In Browning, way up in the northwestern corner of the state on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, “44 percent of pregnant women tested positive for opioid use, according to a 2017 health assessment by the Blackfeet Tribal Health Department and Boston Medica l Center.” (The full report is available here).

l Center.” (The full report is available here).

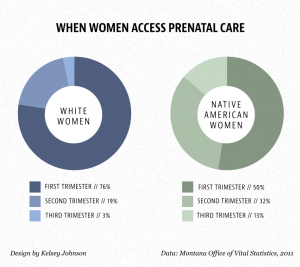

Furthermore, in Montana’s Lake County, which includes part of the Flathead Indian Reservation, almost half of the infants born “were at risk for neonatal abstinence syndrome, the medical term for a dangerous set of withdrawal symptoms in drug-dependent infants including tremors, convulsions, and high-pitched crying.” Add to this that far fewer Native American women receive pre-natal care during the first trimester of their pregnancies than non-native women, and you have the ingredients for significant crisis in Montana’s native communities.

It is easy to provide students with facts and figures illustrating economic, social, and health disparities in native and non-native communities. One must be careful about doing this in order to avoid the sort of “sympathy porn” produced by “journalists” like Dianne Sawyer a couple of years back. (The reservation students’ response to Sawyer’s piece is fantastically effective: If you have not seen it, you can watch it here). It is always worth mentioning to our students what native nations and native peoples are doing on their own to construct solutions to the challenges they face and, indeed, that the problems reservations face may be different in degree but not necessarily in kind from those facing many small towns and rural areas in the United States.

The Washington Post ran a story that offers a moving depiction of reservation life that avoids the cliches and stereotypes and pitfalls into which Dianne Sawyer blissfully stumbled. It’s a profile of Mya Fourstar, a talented fifteen-year-old basketball player  at Frazer on the Fort Peck Reservation in the northeastern part of the state. Fourstar wants to play college basketball, either Division I at Gonzaga or somewhere else, but it’s tough both on and off the court. It is a story students will appreciate, I believe, as they confront their own challenges.

at Frazer on the Fort Peck Reservation in the northeastern part of the state. Fourstar wants to play college basketball, either Division I at Gonzaga or somewhere else, but it’s tough both on and off the court. It is a story students will appreciate, I believe, as they confront their own challenges.

Reservation basketball in Montana is huge. I learned that during the four years I lived in Billings. It was covered on the local television news, and in the pages of the Billings Gazette. It was an exciting, run-and-gun style of basketball, with some incredibly talented players. But it was difficult to recruit these kids to play in college. “They won’t leave home,” I remember a guy in the athletics department at the college where I taught saying. Given the treatment native students faced on my campus, I did not find this surprising at all, though I was then only beginning to grasp the complexity of the challenges these young people faced.

Reservation basketball offers a revealing and, for students, an interesting way to teach about conditions on reservations in the United States, a way to humanize a story that too often is phrased in generalities and statistics that provide by their nature a limited perspective. There is a wealth of material out there for students to read, watch, and think about. There is this CNN story about basketball on the Fort Belknap Reservation, for instance, and you will find many more if you look; news stories like this and this and this and this and this and this, from the now defunct Indian Country Today Media Network, that capture something of the strong feelings reservation basketball can generate; blog posts like this that describe the importance of reservation basketball and others that provide fascinating historical background. And, of course, there is Larry Colton’s book on Crow basketball.

There are, I suppose, as many ways to teach non-Indian students about life in Indian country as there are college professors teaching the subject. What we have to do as instructors, in addition to imparting knowledge and information, is break down and dismantle the stereotypes and uncritical assumptions that serve as the lenses our students look through as they read and write and learn about Indians. There is plenty of bad news out there, and so many of the images to which students are exposed highlight themes of suffering, tragedy, and inevitability. It is worth talking about how limited most discussion of Native American issues actually is. Reservation basketball, like lacrosse in Haudenosaunee communities in New York and Canada, allows a window into a world that is not nearly as remote as our students are led to believe.