On October 7, 1968, Billy Van Tassel died in the Long An Province of South Vietnam. His unit operated near Tan Tru, an area characterized by hard fighting and heavy casualties. He was from Scarsdale, New York, and was two months shy of his twenty-first birthday. He was my second cousin, though I never knew him. He died fifty years ago today.

Because I am a historian, I tend to think a lot about the past. It’s an obvious statement, I suppose. History, I tell my students, is the study of continuity and change, measured across time and space, in peoples, institutions, and cultures. I try to teach my students to understand the significance of the past, to understand past events, and why they mattered. I try to persuade them to see the connections between events, even when at first they are not apparent. Sometimes those connections are incredibly difficult to find, but real nonetheless.

And there were many significant events in 1968. “Identify and give the significance of the Tet Offensive,” my friends and colleagues might ask. It began in January, a series of coordinated North Vietnamese attacks that made clear that the American government’s reports and bulletins about progress in the war were at best rosily optimistic, and at worst brazen lies. Or the assassination of Martin Luther King in April of that year, or Bobby Kennedy in Los Angeles two months later. Identify and give the significance of the Democratic National Convention, where Chicago policemen serving that city’s autocratic mayor bludgeoned anti-war protestors in the streets at the end of the summer.

Billy was one dead soldier, one of more than 16,500 American service members who died during that terrible year, one of the 57,000 Americans who died in all during the Vietnam War. Against that backdrop, his life may not amount to much. Many families suffered.

So what is it that makes an event significant? Does it have to change the world, disrupt the established order of things, ring in a new era, or carry some measurable consequence? I sometimes ask my students to identify the most significant historical events in their lives. They ask for clarification but I encourage them to do their best. They will mention the attacks on 9-11, though they are too young to remember them. They might mention the election of Barack Obama, though some of them are young enough that they do not remember that historic night either. They are so young. They will come up with a range of answers: Sandy Hook, Pope Francis, the tsunami in Japan, the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements, Donald Trump. I listen. Then I ask them again to tell me about the most important event in their lives. What events made you who you are? I suggest to them some possibilities: a first kiss or a first broken heart; the birth of a sibling, a marriage, or a death in the family, an act of cruelty or an act of kindness. Were there events in your life, I ask them, things that you experienced, after which nothing ever was the same? Billy Van Tassel’s death, I think, was one of those events.

I am trying to learn what I can about Billy Van Tassel. He was born in 1947. The Long An Province, where he fought, was a region where the Saigon government and the Communists vied for the control and allegiance of the local populace. If Jeffrey Race is right in his book War Comes to Long An: Revolutionary Conflict in a Vietnamese Province, that struggle already was over as early as 1965, when Billy was still a student at Fordham Prep, still running track, still studying Latin and Greek, still editing the school newspaper and the senior yearbook. He graduated in 1965. I have no idea what he did between then and his enlistment in 1968. His tour began on the Fourth of July, three days after the official beginning of the “Counteroffensive Phase V Campaign.” He served in B Company, 2nd Battalion, 60th Infantry Regiment, in the 9th Infantry  Division of the United States Army. He joined his fellow soldiers in fighting to recover territory lost earlier that year during the Tet Offensive. American forces came in, hard and heavy, and then the South Vietnamese arrived and began rooting out communist fighters. In Race’s view, the strategy could not succeed. They were separating fish from water, the American commanders said, removing the communist fighters from the towns and villages of South Vietnam. But the violence they deployed in this counteroffensive was too extreme, too indiscriminate, and it may actually have increased the number of militants.

Division of the United States Army. He joined his fellow soldiers in fighting to recover territory lost earlier that year during the Tet Offensive. American forces came in, hard and heavy, and then the South Vietnamese arrived and began rooting out communist fighters. In Race’s view, the strategy could not succeed. They were separating fish from water, the American commanders said, removing the communist fighters from the towns and villages of South Vietnam. But the violence they deployed in this counteroffensive was too extreme, too indiscriminate, and it may actually have increased the number of militants.

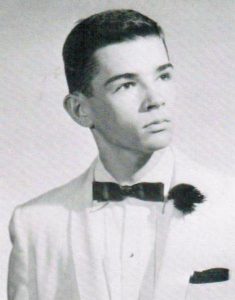

I know nothing of Billy’s experience in Vietnam. He wrote letters home to his mother. I would like to see those letters someday. He asked her to send him magazines about cars, I am told. He was really into cars. I know nothing about the men with whom he served, the battles in which they fought, the horrors they may have experienced, though I hope to learn more. I have found a directory of men who served in the 2nd Battalion during the war, and from that I can piece together a list of names of men who fought in B Company, Billy’s unit. To track those men down, I suspect, will take a lot of detective work, running down a lot of leads. I have found photographs online taken by men who fought with B Company in 1968, but I did not see Billy in any of them, though all I know of his appearance comes from his yearbook photo. War, and the passage of time since someone snapped that senior yearbook photo, might have changed his appearance. I believe there is a lot I still can learn about his brief time overseas, but I am not certain of the strength of the connections he forged while overseas. He died three months after he arrived in Vietnam, “small arms fire” given as the cause of his death. Three months. The semesters at the school where I teach are longer than that. He was a sergeant, promoted posthumously, so maybe he did really well in basic training, or gained a promotion on the battlefield. I wish I knew. There are people out there who know, but I do not know who they are.

Billy Van Tassel volunteered. He was not drafted. That is what the family says. That blows my mind. He went to Vietnam in 1968, well after things seem to have t urned south. He arrived in Vietnam as the anti-war movement at home grew in strength, and after that opposition caused President Johnson to decide against seeking reelection. He arrived in Vietnam after many officials in the Department of Defense had concluded, if we are to believe the Pentagon Papers, that the war could not be won. He volunteered, turning down scholarship offers to Fordham University and Boston College. Despite his family’s pleas that he attend college, he decided to enlist.

urned south. He arrived in Vietnam as the anti-war movement at home grew in strength, and after that opposition caused President Johnson to decide against seeking reelection. He arrived in Vietnam after many officials in the Department of Defense had concluded, if we are to believe the Pentagon Papers, that the war could not be won. He volunteered, turning down scholarship offers to Fordham University and Boston College. Despite his family’s pleas that he attend college, he decided to enlist.

Everyone I spoke with thought that a number of factors went into his decision. “He felt it was a just war at the time,” one of his cousins told me, and he wanted to serve his country. He wanted to do his part. He may have wanted to impress his father, who had served in World War II.

William Van Tassel, Sr., served with the 774th Bomber squadron, 463 Bombardment Group, in the 15th Air Force in North Africa and Italy. The elder Van Tassel entered the service late in 1942. He was thirty-eight years old. He went to Utah for some training, according to his discharge papers, and then to the Mediterranean theatre. The 463rd was a heavy bomber group, flying B-17 “Flying Fortress” planes.

Billy’s dad was classified as an Air Operations Specialist 791, which meant that his job required that he assist

“in the administration of the Army Air Force Operations Office. Supervise or assist in the preparation and maintenance of individual flight records and related reports, preparation of operating orders authorizing flight missions, check lists for periodic instrument tests, and aircraft damage and accident reports, and issuance of flying clothing and personal equipment to aircraft personnel and passengers.”

He also would have supervised or assisted

“in the dispatching of air planes by preparing flight routes and logs of position reports of outgoing or incoming aircraft, obtaining clearances and information as to weather conditions and communication with other stations regarding flights from station and course of transient aircraft.”

This means that it is not likely that he served on board an aircraft. I am trying to learn more, but a letter from the director of the National Personnel Records Center to my uncle’s congressman indicated that his service records were housed “in the area that suffered the most damage” in a fire that took place at the St. Louis facility in July of 1973. “The fire destroyed the major portion of records of Army military personnel for the period from 1912 through 1959, and records of Air Force personnel with surnames Hubbard through Z for the period 1947 through 1963.” Much of what I might have found out there, as a result, is gone, burned up. Even if he were not in combat, maybe seeing so many younger men leave and not return over the course of the two years he spent there had an effect. Casualty rates for bomber crews were high. Everyone agrees that the war changed him, that he was never the same again. He had “combat fatigue.” The kids used to joke that he was not always with it, that he was a “dead head.” Before the war he was “outgoing and personable,” but afterwards, he stopped speaking. He sat at family gatherings, content to hold a baby on his lap, but largely uncommunicative other than that. Family members believe he suffered from what today we might call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

He worked with my grandfather selling tires after the war. A lot of people worked for my grandfather. When my grandfather moved his family to California, William found work cleaning up the courts at a tennis club. His wife Cecelia, my grandfather’s sister, worked as a secretary in the Manhattanville College library. Sometimes they needed help making ends meet. I am told she was friends with Jean Harris, who later was convicted of the murder of Dr. Tarnower, of Scarsdale Diet fame, and may even have visited her in prison.

A damaged man returned from a horrific war, whose son signed up for an unpopular war, and fought there for three months before somebody shot him. The family’s suffering continued. Billy’s sister, Mary Ann, died four years later. She ran a stop sign in Newburgh, New York, right in front of the town hall. It was a sunny afternoon in January of 1973. She hit another car, and her vehicle flipped. The Newburgh newspaper has a photograph of people trying to save her, but you can see the resignation in their faces. There was nothing they could do. Her neck was broken, and she died twenty minutes after the accident.

People seem to expect a lot from historians, when they pay attention to historians at all. They have questions, and they want answers. Sometimes they want reassurance, for us to tell them the course they are following, as nations or as individuals, is right or justified. But some questions have no answers. Or, perhaps, there are questions that historians cannot answer in their role as historians. That uncertainty can be unsettling for some, when the past can provide no path forward and the past, itself, cannot be known. How much can we really know about what happened before us? We learn the facts, and collect what strikes us as relevant. We gather the evidence. We know where to look. But those interior worlds—why did the person we are studying do this or do that? Why did that person make one choice before another? What were they thinking, and what did they feel? Were they happy, sad, fearful, or full of regrets? And what and how does it matter anyways?

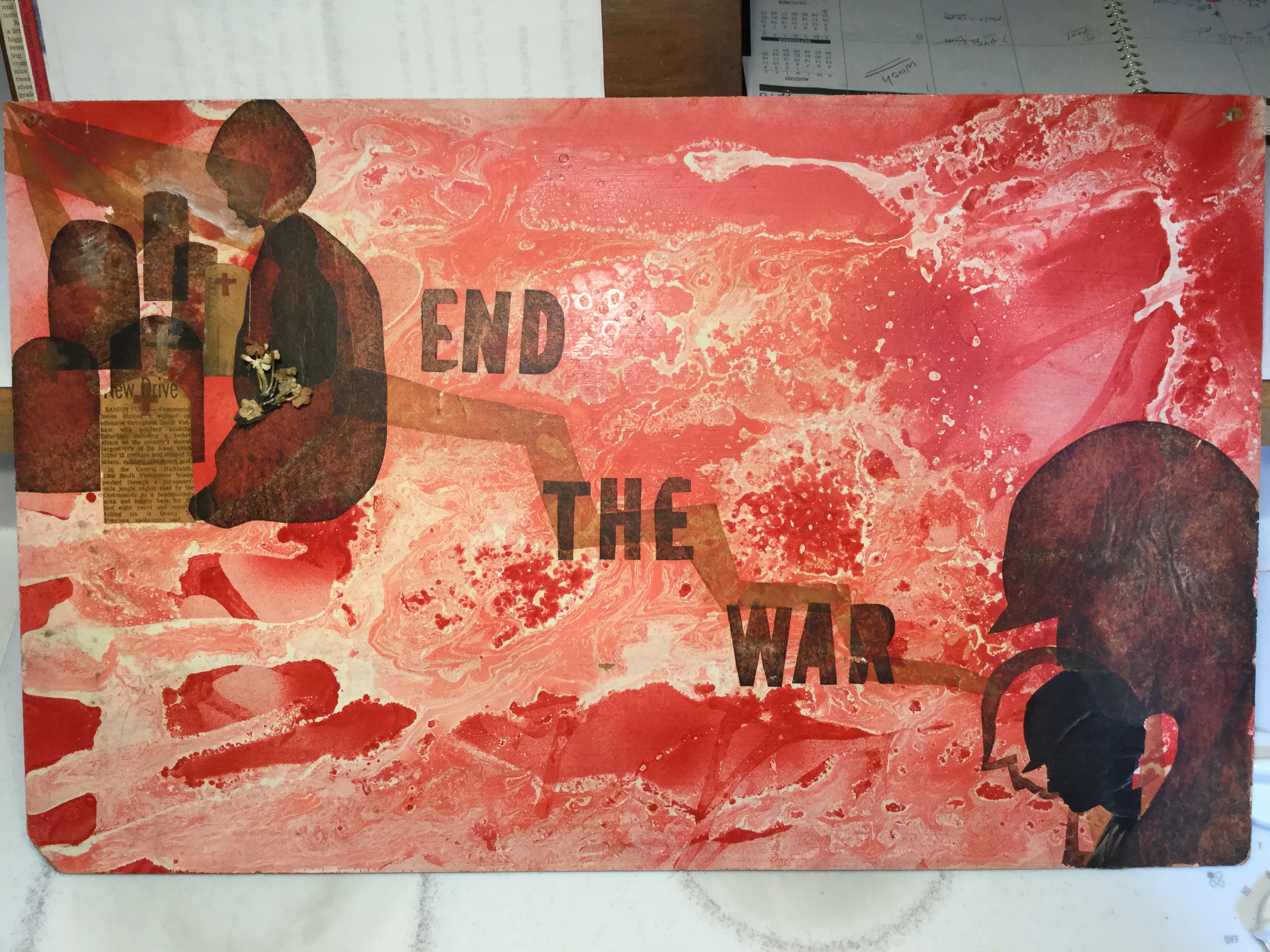

There used to be a poster that hung in the garage of the house where I grew up. My sister remembers it, too. My mom made it when we both were kids. Red and white paint, smeared violently together, with the silhouettes of soldiers and gravestones, and in black block letters across the top, “End The War.”

My dad did not know what happened to it. He thought that maybe he had tossed it. Then we asked my mom. No, she remembered. They still had it. They dug around in the closet of what once had been my sister’s room and they found it.

It has been at least three decades since I last saw that picture, but with the exception of some dried flowers on one of the dark tombstones, it was exactly as I remembered it. It left an impression. I have always wondered why.

The death of Billy Van Tassel made my mother angry. She had opposed the war before Billy’s death, but had not involved herself in protest or anything like that. My sister and I were young. We grew up in a house where I was never allowed to play with guns. That, too, my mom said, was a product of Billy’s death. My own visceral hatred of America’s gun culture? It could have more proximate origins, of course, but the seeds might have been planted long ago.

So many questions. Some I cannot yet bring myself to put on paper. Uncomfortable questions, and certain uncertainties. Historians, I suspect, understand this. We tend to accept the messiness of the past, the inconsistencies we cannot explain, the questions we cannot answer, the riddles for which we lack the last clue. Aware completely that there always will be questions we cannot answer, onward we go anyways, searching for answers. Until we can’t any longer.

Military service records for Vietnam veterans are open to immediate family—fathers and mothers and siblings and children. Billy Van Tassel has no one. His father and mother died long ago. His sister is gone. The National Archives will open his records seventy-five years after his death, a quarter of a century from now. So I talk to those with whom I can speak. I gather what I can find. But there is much I can never know.

Billy’s death must have been a shattering event. And like shattered glass, the cracks spread outward. For some they cut deep and left scars. For the rest of us things were different to be sure, but it is sometimes difficult to see how, and to measure the weight of this event across the span of half a century.

History—the real history of our everyday lives—works like that. We are the things that we remember. We are the things that we forget. We need to be honest about this. We are the product of facts and tales, truths and fables, the things that we know to be real and stories that we take on faith alone. Perhaps we do so foolishly, or because of needs or inclinations long buried or barely recognized. We are what we know and, truth be told, what we can never know.

We head nevertheless into the libraries or the archives. We search about on the internet. Burdened with questions, we head out tired but relentless, searching for answers that may not exist.