Discussions of diversity, equity, and inclusion on too many college campuses are shallow and ineffective when it comes to Indigenous people. For instance, Ricardo Nazario-Colón, SUNY’s Vice-Chancellor for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, recently sent out a memo to SUNY campuses across the state, with his thoughts on the importance of Native American Heritage Month.

“We should take this moment,” he writes, “to recognize the profound contributions, rich cultures, and interminable spirit of the First Peoples of this land.” Nazario-Colón wants to remind his SUNY colleagues “of the deep-rooted connections we all share with the Earth and each other.”

Some of your students will read this and ask, “who could possibly object to that?” Your Indigenous students are likely to ask, “Who’s We?”

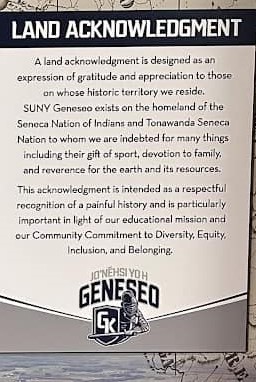

Dr. Nazario-Colón, like me, is an employee of a state that systematically stole Indigenous lands; dragged Indigenous children off to a boarding school that did not close until the late 1950s; sought to eradicate Indigenous languages, culture and religion; and attempted to destroy and dismantle the League of the Iroquois. New York could not have become the Empire State without a systematic program of Indigenous dispossession that at times explicitly violated the laws of the United States. SUNY, as an institution, resisted late until the last century the efforts of Haudenosaunee people to secure sacred objects squirreled away in its collections. Nazario-Colón implicitly accepts the monstrous logic of Justice Ginsburg’s Sherrill decision. Yes, we took your land, but it happened too long ago for us to worry about now.

Dr. Nazario-Colón hopes that “in our journey to deepen our own understanding and acceptance across differences” that we will strive to identify “the core values, emotions, and aspirations we all share.” Doing so, he believes, “fosters unity, solidarity, and a sense of common purpose.” That’s a nice sentiment, but it is far too limited, and Dr. Nazario-Colón has in effect written a perfectly tepid settler-colonial manifesto that fills every square on your DEI Bingo Card. We stole your land. We attempted to destroy your culture. We denigrated your religion. Our Founding Fathers invaded your homelands, burned your towns, raped your women, and murdered your children. We openly and enthusiastically forecasted your extinction and looked forward to your disappearance as a people. If New York had its way, its Indigenous population would no longer exist. But, Hey, let’s get along! Maybe we can even have some “Reconciliation”! But we will not talk about our lies, our crimes, and agreements we have broken. We will not talk about the corruption, deceit, bribery, and dishonesty employed by the State officials who extracted cessions of Indigenous land.

Let’s all get along. Let’s make sure we “see” each other. We may celebrate the “indomitable spirit” we tried to crush, but we will not do any of the heavy lifting, really, to make things right. “We want to learn about you,” Dr. Nazario-Colón suggests. “We want to treat you well.”

“We want our lands back,” Indigenous people might reply. We want SUNY to be a welcoming space for Indigenous peoples, with free tuition, room, and board, and a commitment to hiring Indigenous faculty. We want you to put up or shut up. There have been some exceptions—at SUNY-ESF for example, or with the University at Buffalo’s exciting Indigenous Studies program. But SUNY, as in institution, has shown little interest in any of this. It never really has, and most campuses, like mine, have administrators in charge of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging who do nothing meaningful about this issue.

The problem, of course, is bigger than Dr. Nazario-Colón. His message nevertheless reflects the emptiness and ineffectiveness of so much DEI rhetoric on college campuses, where too few people in too many positions of power at too many schools know way too little about Indigenous peoples, their histories, and their cultures. As a non-Indigenous scholar writing and teaching the history of Indigenous peoples, I find the result galling and offensive, especially on a campus like mine, where we are so closely connected historically to New York’s drive to dispossess and drive Senecas, Oneidas, and Tuscaroras out of the Genesee Valley. You might say that SUNY favors that sort of equity and diversity that costs it nothing, that they are bargain-basement crusaders too cheap to make a real difference. But it’s not about money. It would have cost Dr. Nazario-Colón nothing, after all, to do the work to write a message worth the time it takes to read. The real problem is that they have always been satisfied with gestures empty and performative. The real problem is that they have never adequately shown that they care.