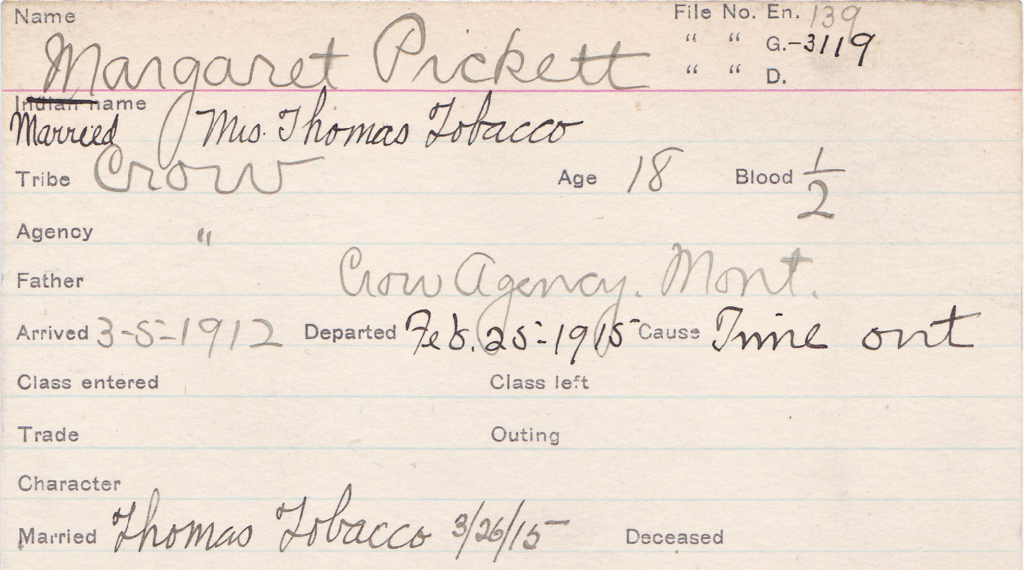

Margaret Pickett, from Crow Agency, Montana, was Julia Peña’s roommate at Mrs. Jacobs’ place. Maggie, as she was called, stayed with Mrs. Jacobs from June until late in August in 1913. Born two decades after the defeat of George Armstrong Custer’s force at the Battle of the Greasy Grass, or Little Bighorn, Margaret was eighteen years old when she arrived at Carlisle in March of 1912. She would remain a Carlisle student for just under three years.

There’s a lot going on in Maggie Pickett’s student file. While she was at school her mother, and her only surviving parent, died of a “paralytic stroke.” In April of 1914, her aunt, Mrs. Little Daylight, requested that Carlisle send Maggie home to the Crow Reservation. She needed help. “My husband died last month,” she wrote, “and I have not been well since then after all my hardships and sorrow.”

O.H. Lipps was Carlisle’s superintendent. He told Mrs. Little Daylight that Maggie “desires to do whatever she can to be of assistance to you.” Prior to sending Maggie home, however, Mrs. Little Daylight must obtain the permission of the reservation agent, a petty tyrant named Evan Estep. He reported to Lipps that “I am inclined to think there is a sinister purpose behind the scheme to get Maggie to come to them.” Estep thought Maggie had been doing well at school and he hated the idea “to have her come here and go back to the old Indian life.” Furthermore, Estep said, “She has no people here.” Her mother and father were dead, and her brothers had all left the reservation. For these reasons, Lipps decided to refuse Mrs. Little Daylight’s request.

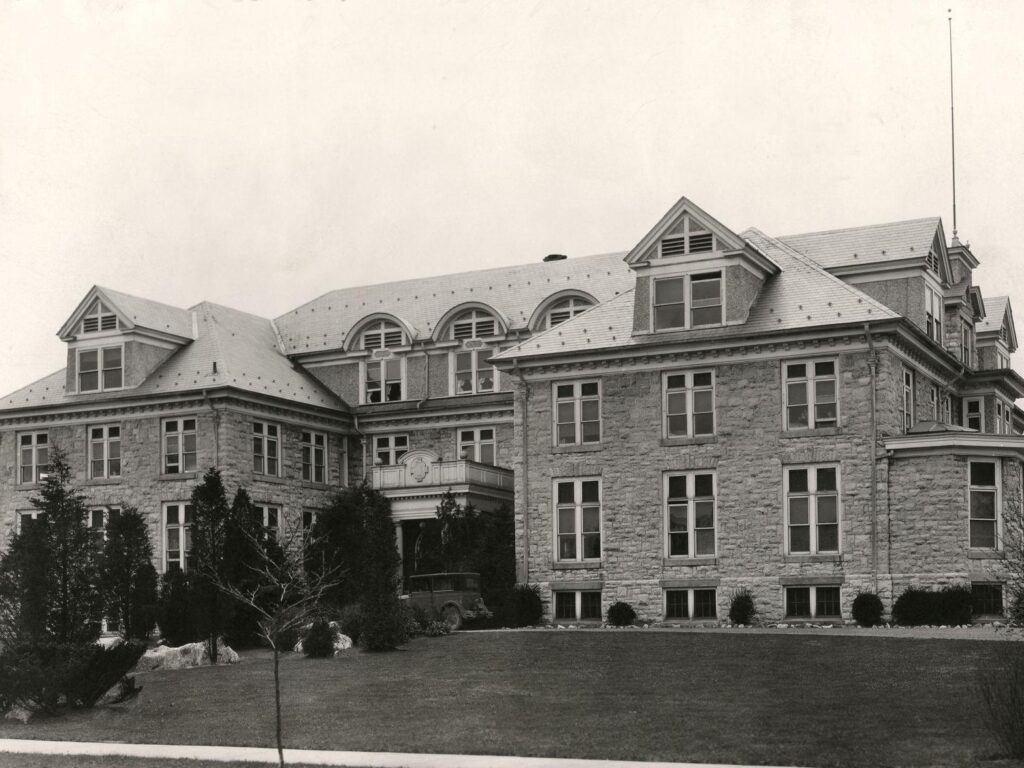

That was April of 1914. One month later, Maggie began working at Todd Hospital in the City of Carlisle. She was learning to be a nurse. She would stick it out at Carlisle, but she wanted Estep to know that she would like to return home, and help her people, as soon as a position opened up on the reservation.

Lipps was impressed by what he heard about Maggie’s work, so he recommended her to Estep in January of 1915. “It is Margaret’s desire to do something for the people at her home in a capacity similar to that of a Field Matron.” She was young for so important a job, Lipps admitted, but her nurse’s training worked in her favor and “She is competent, energetic, and willing.”

Perhaps Maggie asked Lipps to enquire once again about opportunities at home because conditions at Todd Hospital had become unbearable for her. Mrs. Wile, the “Chairman of the Board of Managers” at the hospital, reported that Maggie “had not been doing as well as they knew she could do.” Maggie, Mrs. Wile reported, “was not on good terms with the head nurse, Miss Kruger,” and one other nurse on the hospital staff. They accused her of writing a threatening letter to that nurse, and said that Maggie “received boys from the school as visitors.”

Maggie defended herself. She told Lipps that she did not threaten anyone. She was going to report the nurse for some type of misconduct. She said that, yes, boys from the school visited her, “but it was only as any lady would receive calls.” These letters were exchanged during the third week of February in 1915. Things moved quickly. My the 28th of February, Maggie was at last on her way home to Crow Agency.

Whatever the reason for her departure, Maggie’s supporters at Carlisle had high hopes for her success. She seems quickly to have disappointed them. Within a month of her arrival in Montana, Maggie married Thomas Tobacco. Estep sent word of the ceremony for inclusion in the Carlisle Arrow. In a separate note addressed to Lipps, Estep shared his thoughts more freely. “There is certainly ample room,” Estep wrote, for Maggie “to do some ‘up-lift’ work on her husband, who is a long-haired worthless piece of humanity.” Thomas had been in and out of jail, and Maggie had made a mistake in marrying him. “I believe she hit bottom the quickest of any returned student I ever knew,” Estep wrote, “but if she was to hit it at all I suppose she had just as well go the limit and have it over.”

Estep is an unlikable bigot. He was determined to control the Crows on the reservation even after it was clear he lacked the power to do so. His disdain for the people whose lives he supervised is transparent. Lipps, however, valued his insight. He passed Estep’s note along to have read to the Carlisle girls during the evening prayer meeting. “There was not a more promising girl at Carlisle last year than Margaret,” Lipps wrote. “She frequently assured me of her ambition to be an example of worthy imitation and a force for the up-lift of her people.” He had expected her to return to Carlisle in the fall, continue her studies, and work at Todd Hospital. “I am grieved and disappointed by the way she has turned out.” Maggie, he had hoped, would “prove that the Crow Indians, who are proverbally [sic] a bad lot, were not all bad or worthless.” That Maggie “has yielded to he first temptation,” he concluded, “should be an example to the other girls.”

I am not certain that Maggie knew how much she disappointed Lipps. Three weeks after her marriage, she wrote “to inform you that I have started in to do four ourselves.” Her husband was the son of Tillie Eagle, an ex-Carlisle student. She asked that Lipps send her the money in her school bank account. She was not coming back to Carlisle.

Lipps set her the money, but he could not help but mention the marriage. “When you left here you seemed to be sincere in your desire to continue the same ideals that made you one of the most promising girls Carlisle has had enrolled.” Her marriage to Tom Tobacco while wearing Indian dress “was so prompt a dropping of your ideals that I cannot understand at all.”

No more letters appear in Maggie’s file until February of 1917, almost two years later. “I am getting along nicely and hope every body their [sic] at Carlisle are the same.” She mentioned the cold weather, and the Crow delegation in Washington, fighting attempts to allot the reservation (You can read about those efforts in Chapter 8 of Native America. Maggie said she had some bad news. “Our home was filled with grief over the death of our dear little baby girl the 20th of January.” She was less than a month old when she died from pneumonia. “Mr. Lipps,” she wrote, “I think that days was the saddest days of my life.” She signed her letter “Mrs. Thomas Tobacco.”

Maggie Pickett was training at Todd Hospital to become a nurse. She had wanted to return even before she began working at the hospital. Conflict developed with the other nurses. She went home, married, had a child. She does not show up much after 1917. Her husband Thomas still got in trouble on occasion, but he also was a leading member of the Peyote religion at Crow. She was criticized by Lipps, most harshly behind her back. She worked at making a living on the reservation. She buried a child. But still she took the time to write to Carlisle to wish her fellow students well.