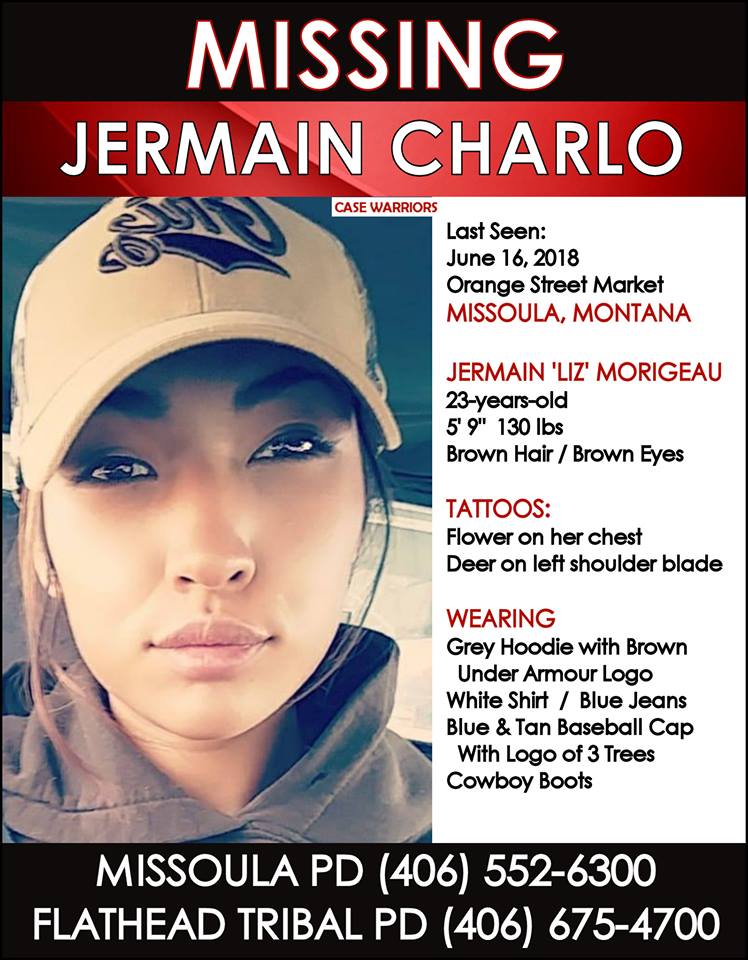

Sometimes I feel like a am teaching America’s original sin. I have felt that way a lot recently. Over the past week I have listened to the first six episodes of Connie Walker’s excellent new podcast, “Stolen: The Search for Jermain.” She focuses on the disappearance, and also the life, of Jermain Charlo, a 23-year-old woman from the Flathead Reservation in northwestern Montana who disappeared from Missoula in the summer of 2018.

During the final year of the Trump Administration, the President designated May 5th as “Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives Awareness Day,” and he established by executive order “Operation Lady Justice,” a task force given the charge to work toward solutions to this incredibly difficult problem. Crimes against humanity are taking place, and even the buffoons in the Trump Administration had to act, even if it was nothing more than an attempt to lure Native American votes in advance of the election. It did not work. Just this week, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the formation of a special unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs. to investigate crimes against Indigenous women. Native American women are murdered at a rate more than ten times the national average.

The national media widely reported on Haaland’s announcement, a refreshing change. More Americans are becoming aware of the pain and grief the #MMIW crisis is provoking in Native American communities, on reservations and off. As Connie Walker pointed out in an interview on NPR, “this issue of violence against Indigenous women and girls isn’t a new issue. This is something that has been going on for decades . . .centuries, even.” What has changed in recent past, Walker continued, is “there’s a growing awareness of this crisis, and there’s a growing awareness about the impacts of that violence on the lives of Indigenous women and girls.”

I worry that this crisis will not hold the attention of the American people for long. Solving this project is one that demands empathy and historical understanding. Both have been in remarkably short supply of late. There are no easy solutions, and it is difficult to truly discern the true scope of the problem. It has been going on for so long.

It was there at the inception. It was present when Christopher Columbus sailed into the Caribbean, his eyes scanning for those things that he hoped would make him a wealthy man. He found no gold, no silver, but he did see a young girl, swimming in the sea. “They should be good and intelligent servants, for I see that they say very quickly everything that is said to them; and I believe that they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me that they had no religion.” In 1495, Columbus enslaved over 1600 Indians, and sent home to Spain “the best males and females.”

Columbus saw a girl,

Splashing in the waves.

He couldn’t find gold.

So he started taking slaves.

It never stops. It rings in your ears as you read this history. The Queen of Paspahegh, captured with her children by the English after they burned her town and wiped out the Algonquian soldiers who defended it. The English officer in charge allowed his men to throw the children into the James River, and to amuse themselves by blowing out their brains in the water. The Queen of Paspahegh, traumatized land grieving her murdered children like so many Indigenous women, was led away from the English fort and stabbed to death in the woods by an executioner too weary to burn her. Algonquian women who surrendered during King Philip’s War in New England, trafficked and sent to death in West Indian Slavery, or torn limb from limb by English dogs of war. The mutilation of Indigenous women’s bodies at Sand Creek and at other sites of genocidal violence. The story has not stopped. Indigenous women go missing, and they die.

Montana, where Jermain Charlo went missing, must be among the worst places for this.

I lived for four years in Montana. I taught at Montana State University at Billings, in a hellhole of a history department. Students from the Crow Reservation were the largest minority on campus, and occasionally a faculty member let them know that they were an unwelcome minority as well. I think about some of the Indigenous women who took my classes there, and the struggles they confronted. I think of the casual racism I heard in Billings, on campus and off.

I think about my students in Geneseo as well. I imagine that many of them, when they lived at home, went out at night with their friends. Your parents are not idiots, I told them. They know you may be out having a good time. They know that sex and alcohol and drugs might be involved. They have to trust that you will make the right decisions. Even when we parents do not trust you to make the right decision, we have to, I said. You go out and you come home later than you said you would, and your parent might be angry, they might ask you lots of questions, they will pester you. You might see this as the ultimate buzzkill, or as disrespectful. It might bother you that your parents do not seem to trust you, or that they worry so much. I have children, so I share with my students one thing I know for certain: that when you get out of your parents’ sight, they worry. When you are not where you said you would be when you said you would be there, no matter how old you are, they will worry because they are afraid. We are afraid. Really. Because there is nothing worse than thinking that something bad happened to your child, or that somebody hurt your child. So, imagine, I tell them, the scene in your house if you did not come home. Imagine the scene without you in it. Imagine your parents planning your funeral or, perhaps, for years wondering what happened to you. I think if you asked your parents, “What’s the worst thing that could happen to you?” they would say that something terrible happened to my child, or that someone hurt my child. I know I would say that. I ask my students to imagine what it would do to your parents to lose you.

Because all the evidence suggests that thousands of Indigenous families in Canada and the United States experience this “worst thing.” Savannah Grey Wind’s family, for instance. Savanna was eight months pregnant. Her neighbor in a Fargo apartment complex lured her inside, hit her on the head, and while she was still alive, ebbing in and out of consciousness, cut the baby out of her womb. Together, Brooke Crews, that neighbor, and her boyfriend, cleaned up the blood, disposed of the clothing, and wrapped up Savannah’s body in plastic sheeting before dumping her body in the river, where kayakers found her some time later. They attempted to raise the baby as their own, before the authorities arrested them. The baby is how with her father.

Or Mildred Old Crow, who disappeared in November of 2020. She was eight years old. Her body was found in February of 2021. Her guardians had been charged in tribal court for endangering the welfare of a minor. Eight years old. Native Americans make up 7% of Montana’s population, according to one set of figures, but they comprise a full 25% of the missing persons in the state. In February of this year, accordig to another source, there were 167 active missing persons cases in Montana. 53 of them, or 31%, were indigenous.

Just a month before the discovery of Mildred’s body, authorities found the body of Selena Faye Not Afraid on the Crow Reservation. She was

sixteen. She died of hypothermia, exposure, after walking away from a broken down car. It was January in Montana. It was viciously cold. Why did she leave? What caused her to leave?

And Kaysera Stops Pretty in Places. She was eighteen, played basketball and ran cross-country. She performed in school plays at Hardin High School and wanted to act. She had been at a house party, but disappeared. She was found several days later, by a passerby, who discovered her body behind a woodpile in the backyard of a different house. Nobody knows how she got there, and her cause of death is “undetermined.”

It is difficult teaching this subject. Sometimes it can grind you down. It is difficult, I found, to listen to parts of Connie Walker’s podcast. This is an enormous problem, but I am a historian. Nothing is inevitable, I tell my students. Every things has causes. This is not a force of nature or an act of God. These are criminal acts by individuals committed against Indigenous women and girls. It does not have to be this way. At least, that is what I believe. Why are so many Native American women and girls missing? Though there is still by all accounts a shortage of evidence as to the scope of problem, everyone acknowledges that the problem is substantial. It is causing devastation and grief. You can read the tributes on Selena’s page at the Dahl Funeral Chapel. You can listen to the voices of Jermain Charlo’s friends and family members in “Stolen.” It is right before your eyes. The government has slowly started to respond.

Were these young women white, and had they disappeared from the suburbs, this problem would already have been solved. It only gets us so far to point out that truth. These are often crimes committed on the margins, on remote reservations or in American cities where, if you want, you can feel as isolated and alone as if you were walking in the woods. None of them disappear without a trace. There are clues, incomplete, but enough of the picture is complete to suggest that a solution to the puzzle is near. And there are the people left behind: Jermain had two children, but also the sisters, friends, parents and relatives, concentric circles of grief, radiating outward like ripples on the surface of a pond.