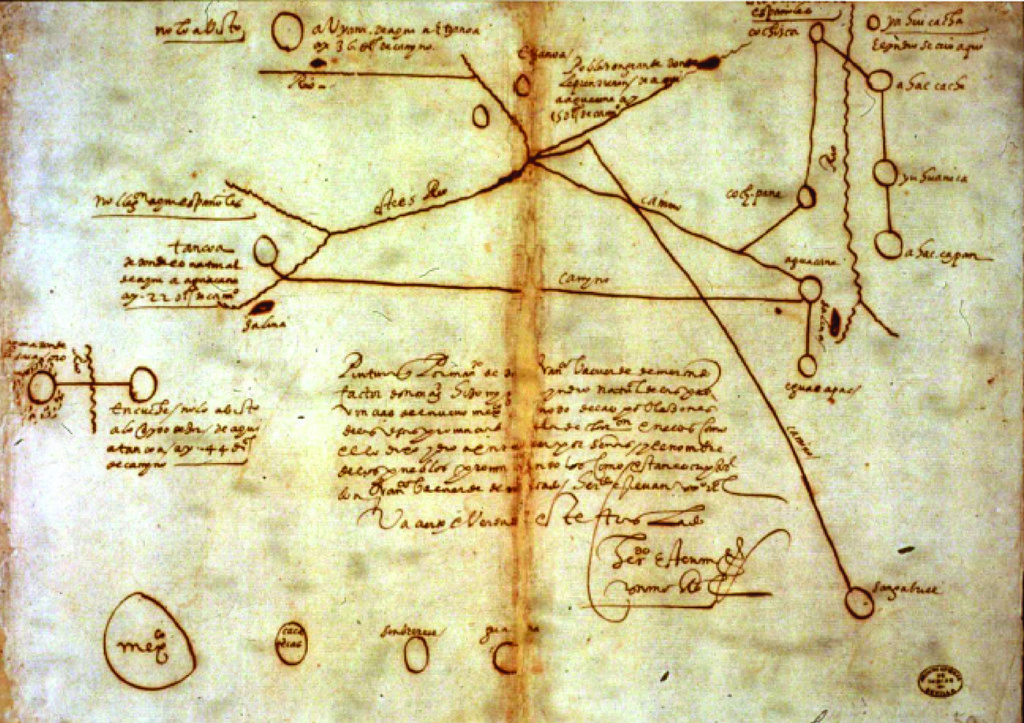

Donald Blakeslee, an archaeologist at Wichita State University, may have found with his students the site of Etzanoa, where perhaps 20,000 people lived along the Walnut and Arkansas Rivers in Kansas between 1450 and 1700.  Both Francisco Coronado in 1541, and Juan de Oñate sixty years later, passed through this part of what is now Kansas. I discuss both the Coronado and Oñate expeditions into the Great West in Native America, and I look forward to sharing Blakeslee’s work with my students. I read about investigations at Etzanoa in an article that appeared in the Wichita Eagle back in April and another piece, written by David Kelly, that appeared in the Los Angeles Times last week. I look forward to seeing more scholarship published soon.

Both Francisco Coronado in 1541, and Juan de Oñate sixty years later, passed through this part of what is now Kansas. I discuss both the Coronado and Oñate expeditions into the Great West in Native America, and I look forward to sharing Blakeslee’s work with my students. I read about investigations at Etzanoa in an article that appeared in the Wichita Eagle back in April and another piece, written by David Kelly, that appeared in the Los Angeles Times last week. I look forward to seeing more scholarship published soon.

As Kelly writes in the Times, as Oñate’s part explored the Plains in search of gold, slaves, and Christian converts,

they ran into a tribe called the Escanxaques, who told of a large city nearby where a Spaniard was allegedly imprisoned. The locals called it Etzanoa.

As the Spaniards drew near, they spied numerous grass house along the bluffs. A delegation of Etzanoans bearing round corn cakes met them on the riverbank. They were described as a sturdy people with gentle dispositions and stripes tattooed from their eyes to their ears. It was a friendly encounter until the conquistadors decided to take hostages. That prompted the entire city to flee.

Oñate’s men wandered the empty settlement for two or three days, counting 2000 houses that held 8 to 10 people each. Gardens of pumpkins, corn and sunflowers lay between the homes.

The Spaniards could see more houses in the distance, but they feared an Etzanoan attack and turned back.

That’s when they were ambushed by 1500 Escanxaques. The conquistadors battled them with guns and cannons before finally withdrawing back to New Mexico, never to return.

This, then, was an important site. The Plains may seem empty. Spaniards crossing them felt at times like they were lost at sea, the lack of landmarks baffling to them. But in the heart of the continent, an area beyond the interests of so many historians of the colonial period, stood a Native American city with influence, power, and wealth. American history looks much different, and much more rich, when we view native peoples as central to the story.

Between the first and second editions of Native America, I learned of the important work of Richard and Shirley Flint. We ate dinner together in Providence, all of us attending a meeting of editors working on Oxford’s planned edition of Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations. I read as much of their work as I could get my hands on. Their articles compelled me to revise significantly my coverage of Coronado. We live and learn. We read and revise. It is a part of our jobs with which historians are comfortable, but that I do not feel we always impart successfully to our various publics: that the record is never settled, that new evidence can and will be found and, sometimes, quite literally unearthed. With that new evidence comes the obligation to reassess what we thought we knew. It is challenging. It can be frustrating at times. But it is exciting, too. Every year the historians I know re-write lectures, revise their reading lists, reconsider assignments and discussion sessions in light of new scholarship and new discovery.

As for the site Blakeslee investigated in Kansas, much of it remains unexcavated and on private land. Talk is beginning about organizing tours, to increase public awareness and education about a city that may have rivaled Cahokia in terms of its power and regional influence. Done well, that offers an exciting prospect.