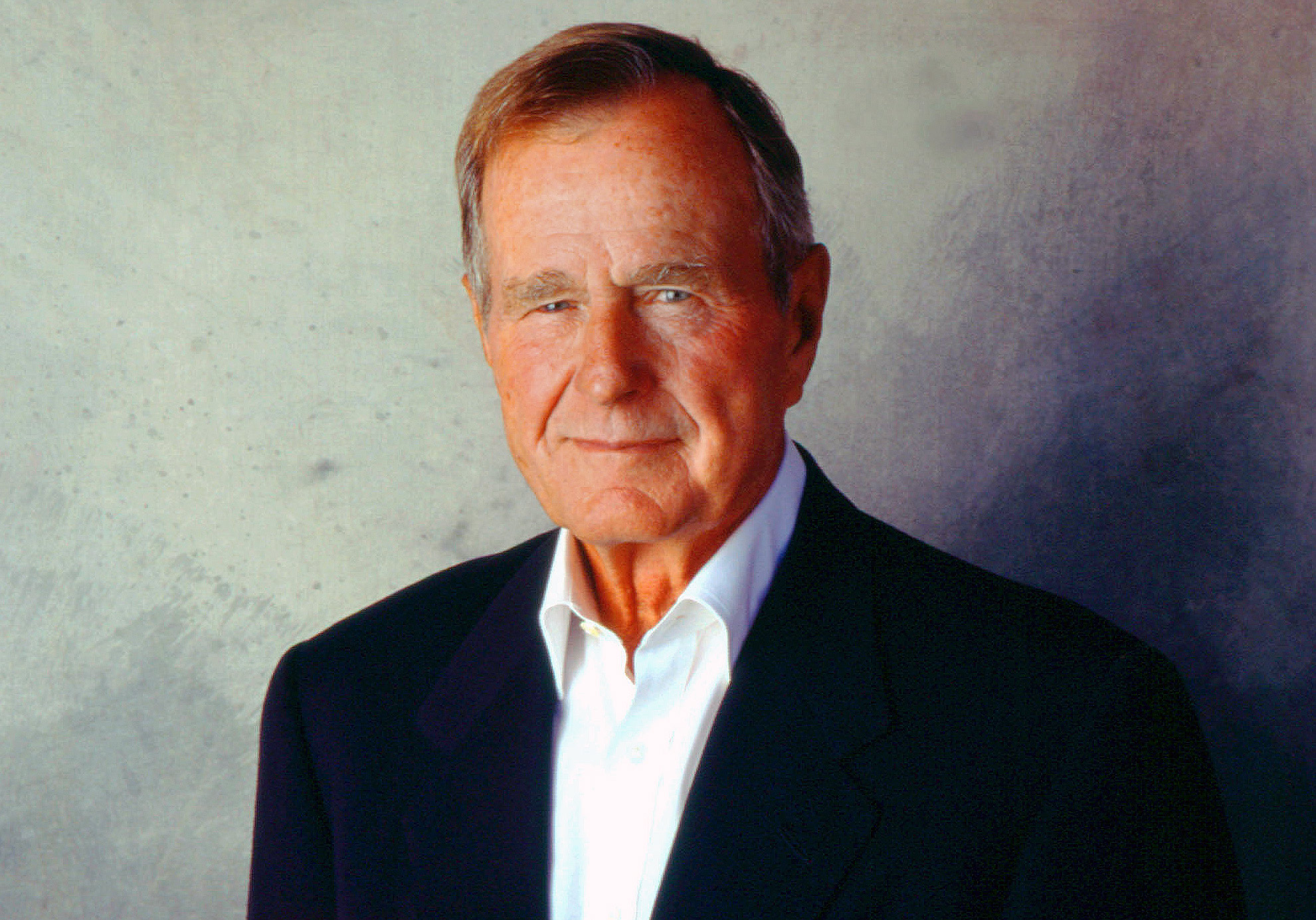

President George Bush died late last week. His funeral will take place in the next few days at the National Cathedral in Washington, before his family flies his body to College Station, where they will bury him on the grounds of his Presidential Library at Texas A&M University.

Bush lived a long life in public service. He served as a pilot in the second World War, as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, as the US Ambassador to the United Nations, as Vice-President under Ronald Reagan, and President himself from 1989 to 1993. Some have praised his temperament, his character, his devotion to service. Some have criticized his failures and his mistakes.

I am ambivalent about much of this. I agreed with few of his policies, and was disappointed by his many shortcomings, but I also can see the merits in viewing him as one of the most consequential one-term presidents in American History. While I imagine I would have agreed with him on few issues, I expect he would have been an interesting and interested conversationalist, a man who stands in stark contrast to the current occupant of the White House.

This is the final week of classes at Geneseo, and in my Native American survey course, we will be discussing some of the accomplishments of Bush in the realm of Indian affairs as I rush to do as much as I can to bring us up to the very-near present.

In June of 1991, President Bush issued a special statement on Indian policy. He would continue the policies of the Reagan-Bush years by “recognizing and reaffirming a government-to-government relationship between Indian tribes and the Federal Government.” This relationship, he continued, “is the result of sovereign and independent tribal governments being incorporated into the fabric of our nation, of Indian tribes becoming what our courts have come to refer to as quasi-sovereign domestic dependent nations.” This relationship “has flourished, grown, and evolved into a vibrant partnership in which over 500 tribal governments stand shoulder to shoulder with the other governmental units that form our Republic.” Referencing the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, an important piece of legislation that allowed tribes to “contract” with the federal government to run programs on their reservations, Bush pointed out that “an Office of Self-Governance has been established in the Department of the Interior and given the responsibility of working with tribes to craft creative ways of transferring decision-making powers over tribal government functions from the Department to tribal governments.”

Recognizing the problems that would lay at the heart of the Cobell case, President Bush planned to establish within interior an office responsible for “insuring that no Departmental action will be taken that will adversely affect or destroy those physical assets tat the Federal Government holds in trust for the tribes. He took pride, he said, “in acknowledging and reaffirming the existence and durability of our unique government-to-government relationship.” Bush make clear that he could not monitor events in every native nation, and that he could not “deal directly with the multiplicity of issues and problems presented by each of the 510 tribal entities in the Nation now recognized by and dealing with the Department of the Interior,” he would do what he could. He concluded by stating

The concepts of forced termination and excessive dependency on the Federal Government must now be relegated, once and for all, to the history books. Today we move forward toward creating a permanent relationship of understanding and trust, a relationship in which the tribes of the Nation sit in positions of dependent sovereignty along with the other governments that compose the family that is America.

That is certainly not a ringing endorsement of tribal sovereignty and at best a qualified statement acknowledging native nationhood. Still, Bush’s presidency was a consequential one for native peoples. During his four years in office, the United States Supreme Court decided the important religious freedom case of Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith adversely for the Native American drug treatment counselor who originally brought the case, and Duro v. Reina, which expanded upon the logic of Oliphant by barring tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-member Indians.

Bush can not be blamed for the actions of the Supreme Court, of course, and he ought to be acknowledged for some o f the legislation that he signed. In November of 1989, he signed the National Museum of the American Indian Act, which would “give all Americans the opportunity to learn of the cultural legacy, historic grandeur, and contemporary culture of Native Americans” through the construction of a American Indian Museum on the National Mall. He signed legislation establishing a joint federal-state Commission on Policies and Programs Affecting Alaska Natives and, later, an act establishing an “Advisory Council on California Indian Policy.” He signed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 “to promote the development of Indian arts and crafts and to create a board to assist therein,” in establishing standards of authenticity for Native American arts and crafts. And most importantly, President Bush signed the very important Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which required that any entity receiving federal funds identify and offer to return to native peoples the human remains they housed in their collections.

f the legislation that he signed. In November of 1989, he signed the National Museum of the American Indian Act, which would “give all Americans the opportunity to learn of the cultural legacy, historic grandeur, and contemporary culture of Native Americans” through the construction of a American Indian Museum on the National Mall. He signed legislation establishing a joint federal-state Commission on Policies and Programs Affecting Alaska Natives and, later, an act establishing an “Advisory Council on California Indian Policy.” He signed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 “to promote the development of Indian arts and crafts and to create a board to assist therein,” in establishing standards of authenticity for Native American arts and crafts. And most importantly, President Bush signed the very important Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which required that any entity receiving federal funds identify and offer to return to native peoples the human remains they housed in their collections.

George Bush, like many historical figures, was complicated. Historians can accept that. He lived a long life. He served his country. He did some important things, and he did things that were destructive. There is no need to rush to judgment about the meaning of Bush’s career. I will try to get my students to assess these policies this week, add them up, and decide how significant they were for America’s native nations.