Late last month, Douglas J. Lucia, the Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Syracuse, expressed the hope that he might meet with the pope to discuss the 15th-century papal donation granting the Catholic powers the right to colonize the Americas. He wanted to obtain “a public acknowledgment from the Holy Father of the harm these [papal] bulls have done to the Indigenous population.”

Bishop Lucia’s announcement was greeted favorably. Doing away with the papal bulls would be an important symbolic gesture. But that’s all it is. The Catholic Church has destroyed the lives of millions of Indian people and justified the destruction of many, many more. Lucia’s action does not begin to address the historic and continuing damage his church has caused Indigenous peoples across the American continents, and across parts of seven different centuries.

Though significant, the papal bulls were hardly the worst crime committed by agents acting in the name of the Catholic Church, and we’re making too much of the resulting “Discovery Doctrine.” The French who settled what came to be known as Canada, after all, did not care what the Pope told the Iberians. The English, who described the Pope as the “Anti-Christ” and the “Scarlet Whore of Babylon,” could not have cared less what he told Spanish and Portuguese monarchs. The English, in fact, were remarkably unintellectual about colonization, a process they viewed as a fait accompli, the only justification needed that it might make them rich and provide an opportunity to stick it to their abundant Catholic enemies. The entire history of European colonization in the Americans involved Europeans ignoring each other’s New World claims. Were there no papal donation, there is little reason to believe that English and French colonization would have followed a different course. The most enlightened English colonizers believed that Indigenous peoples just might have the capacity to abandon their savagery and become like them. They were often shouted down by other colonists who saw Indigenous peoples as “errors of nature, of inhumane birth/ the very dregs, garbage, and spawne of the earth.” People with beliefs like that could kill Indians and dispossess them with a staggering brutality.

If we want to understand the Indigenous past, we should spend less time talking about what white people did or did not do and focus instead on the native peoples who confronted their would-be colonizers. What the pope said did not matter to them one bit, and let’s not underestimate the longevity of Indigenous power on this continent. The Jesuits who first attempted to plant a mission at Onondaga Lake in the 1650s, for example, despite their high hopes, realized too late that they served merely as hostages who insulated the Onondagas from French assault and attracted Catholic Wendats to enter the Longhouse through its smoke hole and settle under the Tree of Peace at Onondaga. When the Jesuits were no longer useful, they realized their lives were in danger. They constructed the boats they used to flee in the one place they knew Onondagas would never see them: inside of their church. Three centuries after the papal donation, Haudenosaunee peoples, including Onondagas, entered into a treaty at Canandaigua that recognized their right to the “free use and enjoyment” of their lands, over which the United States neither claimed or exercised any real power at all.

Though Chief Justice John Marshall’s racist opinion in Johnson v. McIntosh in 1823 made use of what has come to be known as the “discovery doctrine” in a flawed and lazy effort to bring some order to a chaotic process characterized by viciousness, avarice and deceit, and though his toxic ruling has had a devastating effect on the field of American Indian law since 1823, his sloppy historical work was a justification for dispossession, and not its cause.

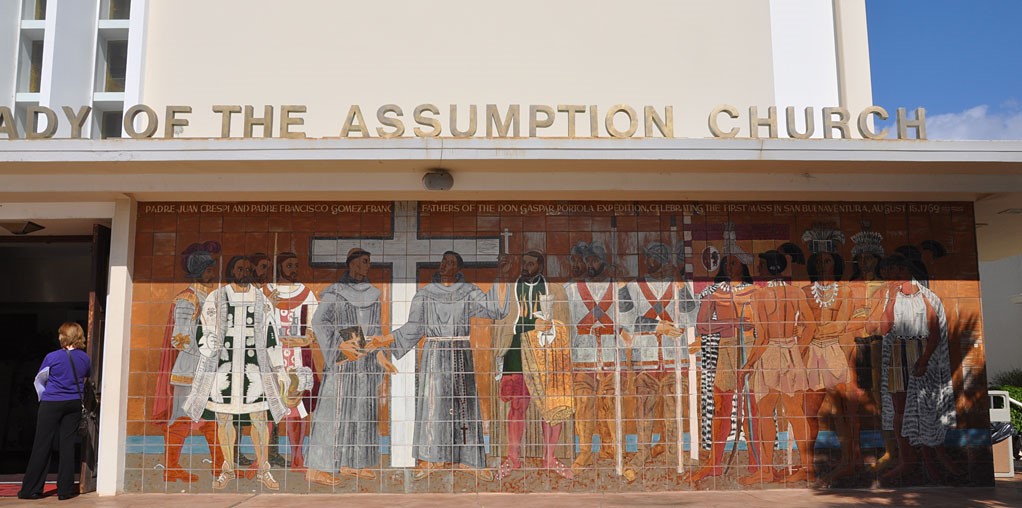

And from the Pueblos sexually mutilated on the order of Franciscan priests in the seventeenth century, to those Indigenous Californians enslaved in missions founded by the sainted Father Junipero Serra, to the children who have died in the century past in Canadian residential schools, and the ongoing occupation of the sacred site at Mount Graham, the sins of the church in which I was raised are great.

Indigenous peoples have faced efforts to take their souls, steal their lands, burn their homes and eradicate their culture. Catholics and other Christians have for much of their history sanctioned and engaged in these genocidal policies. But native peoples always resisted. Maybe Bishop Lucia deserves praise for calling out the historic conduct of the Catholic Church. But for an adequate penance it is going to take much more than the empty symbolism of repealing an ineffective legal doctrine that nobody in early North America during the first three and a half centuries of European colonization cared about at all.

This essay appeared originally in the Syracuse.com on July 19, 2021.