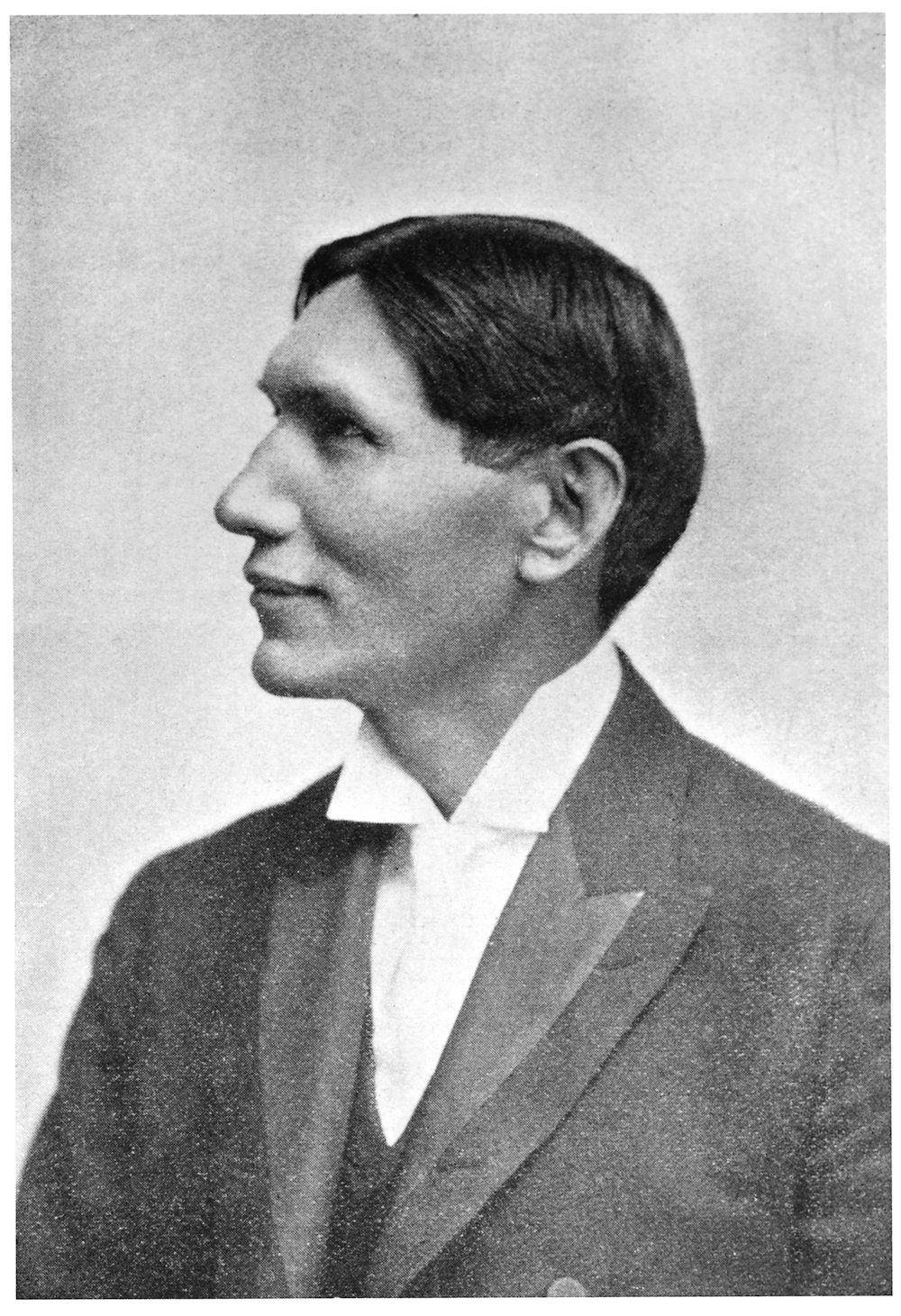

Shortly after the end of the First World War, a conflict which no historian has yet to show was fought for causes that would have justified the loss of a single human life, the great Dakota reformer, writer, and intellectual Charles Eastman hoped that the post-war world would better recognize the rights of the world’s “little peoples,” including Native Americans, “to plead for a better observance of their individuality and rights by the more powerful and ruling nations.” Eastman hoped that in the postwar world the imperial powers might admit “that every race, however untutored, has its ideals, its standards of right and wrong, which are sometimes nearer the Christ principle than the common standards of civilization.”

Eastman is a fascinating thinker. I wish I had more time each semester to expose my students to more of his work. As the newly appointed doctor at Pine Ridge nearly two decades before, he was one of the first people on the scene in the aftermath of the massacre at Wounded Knee. The experience affected Eastman deeply. He saw the mangled bodies, and did what he could for the small number who had miraculously survived the federal artillery and gunfire. When he reached the site of Big Foot’s camp, he “saw the frozen bodies of men who had been in council and who were almost as helpless as the women and babes when the deadly fire began.” Eastman struggled to keep his composure. All about him he heard the “excitement and grief of my Indian companions, nearly every one of whom was crying aloud or singing his death song.” He found a few survivors, all babies. All were adopted by white people. “All this was a severe ordeal for one who had so lately put all his faith in the Christian love and lofty ideals of the white man,” he concluded, “yet I passed no hasty judgment, and I was thankful that I might be of some service and relieve even a small part of the suffering.”

A Santee Sioux, Eastman was born in 1858. His father had participated in the uprising in Minnesota and fled after the Santees’ defeat in 1862. Federal troops captured Eastman’s father and imprisoned him at Fort Snelling. Nobody told the boy. Eastman believed that his father had been among those hanged in the aftermath of the uprising. All these are stories that I tell in Native America.

With his grandmother, Eastman joined those who fled from Minnesota out onto the Dakota prairies and from there to southwestern Manitoba. There Eastman lived what he described as a beautiful life. But then his father appeared, a decade after his capture. The father had converted to Christianity during his captivity, taken up farming near Flandreau, South Dakota, and had come to believe firmly in the value of an American-styled education. He determined to prepare his son to live in a nation dominated by white people. He sent the boy to the Santee Normal School, a boarding institution that taught crafts and trades but also instructed its mostly Sioux students to read and write in their own language. From Santee, Eastman moved on to Knox College, Dartmouth, and, finally, the medical school at Boston University.

Eastman represented a new generation of well-educated native people, familiar fully with both their own culture and the norms and values of white society. Born after the reservation period had begun, they had lived their entire lives with at least some awareness of federal efforts to dismantle their culture and their traditional ways of living. They wrote and spoke English, and emphasized that native peoples had much to contribute to the United States. They hoped to establish a place for native peoples in modern American society. They saw themselves both as Americans and as representatives of an assertive Indian “race.”

After the war, he wrote in the pages of the American Indian Magazine his hopes for the future.

The world is tired, sick , and exhausted by a war which has brought home to us the realization that our boasted progress is after all mainly industrial and commercial–a powerful force, to be sure, but being so unspiritual, not likely to be lasting or stable. On the other hand, being so powerful it might have been expected to be destructive and therefore cruel. The intellectual development connected with it has been largely heartless and soulless. The education of the child has subordinated his higher instincts to the necessities of business. Christ has been preached in vain, since his most unmistakable and unequivocal declarations are directly opposed to our excess of materiel development, social injustice and the accumulation of wealth.

Eastman lived until January of 1939, just as the world was preparing to tear itself into pieces once again in an effort to defeat the horrid racist violence of Hitler’s odious regime. There is a sadness and a disappointment that runs through his writings that is sometimes difficult for me to shake.

Hard reality. The “christianity” of manifest destiny