Today the new citizenship exam goes into place, with consequences for those who seek to become citizens of the United States. The new examination is different, to be sure. It is a quiz more than a test, assessing the applicants factual knowledge of arbitrarily selected bits of information about American history and the nation’s political system. The questions in Part A focus on “Principles of American Government,” those in Part B on “Systems of Government,” and those Section C on “Rights and Responsibilities.” Then follow a couple of dozen questions on American History divided into the “Colonial Period and Independence,” the “1800s,” and “Recent American History and Other Important Historical Information.” Finally, there is a small selection of questions on “Symbols” and “Holidays.”

There has been abundant criticism of the new exam. Widely viewed as part of Stephen Miller‘s plan to make American citizenship more difficult to attain, critics have asserted that the new test is more difficult, especially for those with limited English proficiency. As Maeve Higgins pointed out in the New York Times, the “potent administrative changes” put into effect by the Trump Administration, including those to the test, are “insidious.” “However innocuous some changes may seem, they illuminate the end goal: curbing legal immigration.”

These are, indeed, important critiques, not to be discounted. The Trump Administration’s hostility to immigrants and refugees is well documented and utterly undeniable. What bothers me, however, is the sheer inanity of the enterprise. Of course new citizens should know something of the country to which circumstances have led them to apply for citizenship. This is not the way to accomplish it. “Here are some questions with the answers,” the government says. “Memorize enough of these and, after all the other paperwork and expenses you have endured, you are good to go.” Memorization and regurgitation pose the final hurdle.

Yet however difficult the new quiz, I am willing to bet that an enormous number of American citizens would not pass. This morning I gave my students the quiz, randomly selecting 20 questions from the list of 128.

- 2. What is the supreme law of the land?

- 3. Name one thing the U. S. Constitution does?

- 6. What does the Bill of Rights protect?

- 9. What founding document said the American colonies were free from Britain?

- 15. There are three branches of government. Why?

- 25. How long is a term for a member of the House of Representatives?

- 29. Name your US Representative.

- 33. Who does a member of the House of Representatives represent?

- 34. Who elects members of the House of Representatives?

- 48. What are two Cabinet-level positions?

- 50. What is one part of the judicial branch?

- 69. What are two examples of civic participation in the United States?

- 77. Name one reason why Americans declared independence from Britain

- 80. The American Revolution had many important events. Name one.

- 83. The Federalist Papers supported the passage of the U. S. Constitution. Name one of the writers.

- 88.James Madison is famous for many things. Name one.

- 91. Name one war fought by the United States in the 1800s?

- 99. Name one leader of the women’s rights movement in the 1800s

- 114. Why did the United States enter the Persian Gulf War?

- 124. The Nation’s first motto was ‘E Pluribus Unum.” What does that mean?

My students did fine. They are readers and thinkers. College students do not deserve the critiques they get from so many of the oldsters. But look at the news. Listen to the rhetoric coming from our leaders in the Senate and Congress. We have constructed a country that allows civic illiterates who have little knowledge of what the Constitution says, what it means, and from whence it came to flourish in the nation’s public

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22005719/AP_20197105978754.jpg)

life. The permissible answers to the questions on the quiz, as is the entire endeavor to quiz would-be citizens in the first place, is ideological and intended to advance an uncritical patriotism. Senators represent the citizens of their states, the quiz says, not the people. So too with Congressional representatives, a notion that would have surprised the Founders. Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton all are “famous for many things.” Aspiring citizens should be ready to name one, as if knowing any of this quiz show data leads directly to meaningful and productive citizenship.

Native Americans show up in a couple of questions. If applicants are asked “who lived in America before Europeans arrived,” they had better be ready to say “Native Americans” or “American Indians,” and they need to know the name of at least one Indian tribe. This hardly prepares new citizens to comprehend America’s centuries-long history of dispossession and colonialism. At the same time one can correctly answer the question about the “many documents” that “influenced the U. S. Constitution” by mentioning the “Iroquois Great Law of Peace,” even if few historians actually agree.

Not knowing the answers to these questions has not kept many Americans from participating in politics, with disastrous results. Most Americans, after all, according to a Woodrow Wilson Foundation study from 2018, would fail the old version of the test. Americans who do not know what the Constitution says, for instance, are in a poor position to challenge the machinations of a party or party leader intent on taking from them the rights that Constitution protects. The last four years ought to convince you that we are indeed in a crisis. Too many Americans, too ignorant of their country’s history (or any history for that matter), and functionally illiterate about how the American constitutional system ought to operate, make fit tools for tyrants.

There is evidence that the Trump administration is intent on wrecking the place on the way out, like an angry tenant evicted from an apartment who wants to get back at the people who turned him out. That includes the issue of immigration, as the Trump administration rushes to complete more of its silly border wall, and to put new restrictions in place like this ineffective test. But what we need are fewer restrictions on immigration. Hell, drive through the Midwest, and the Plains states, and you can see the massive depopulation, desolation, and devastation that might be reversed by immigration. A taco truck on every corner would be far more economic enterprise than many of the small emptying towns of America’s broken heartland have seen in a generation. What

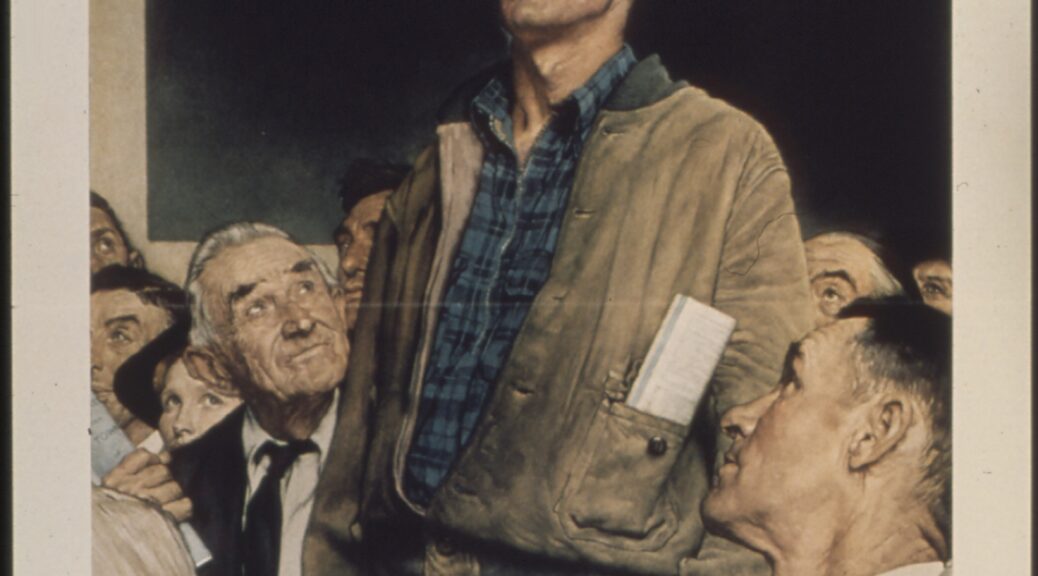

we need is more discussion of making citizenship productive, informed, and meaningful. Americans long have viewed citizenship as a mold into which immigrants must be pressed. Native Americans, too, who formally became citizens in 1924, were prepared for “rights and responsibilities of citizenship” in the same rote, heavy-handed manner as immigrants today. Citizenship is seen as a bar one must clear, an objective achieved, not as something one lives, breathes and does. Citizenship does include both rights and responsibilities, as the new exam suggests. One of those responsibilities is active and informed engagement in the body politic, to nurture a sense of duty and selflessness, and to think of the nation before the stock portfolio. We are in this together. “It takes all of us,” as the lettering on the back of the football players’ helmets reads. Citizenship is not an entry pass to a country, not in a thriving democracy anyways. It must be a way of life.