And, Dear Reader, I feel some ambivalence about it. If you follow the news from Indigenous America at all, you likely heard about the report. It received widespread attention. Dr. Holly Kathryn Norton, the Colorado State Archaeologist, wrote the report for History Colorado, part of a state-mandated investigation of boarding school history in the state. Norton was assisted by a team of researchers. Norton and her colleagues focused most closely upon the Grand Junction Indian School, also known as the Teller Institute mostly in the state, and the Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School. The first was an off-reservation federal boarding school. The latter stood much closer to the reservation community it wished to serve.

Much of the coverage of the History Colorado report was written by people, I suspect, who did not read the report in its entirety. Had they done so, they might share my desire that Dr. Norton had been more thorough, energetic, and creative in the execution of this important work.

What the investigators did find will not surprise historians familiar with the long history of federal Indian boarding schools. The founders of the Teller Institute, for instance, had trouble finding qualified faculty, staff, and administration. The school’s first doctor was known for his “bad character,” even if Norton provided no specific examples demonstrating precisely how. The school’s first superintendent “used unethical methods of recruiting students, even by the standards of the day,” but, again, no evidence is provided for the reader to see precisely what he did.

Families described poor food, substandard buildings, filth and cold. The 600 students who attended the Teller Institute over the course of its twenty-five year existence, and their parents, found the school wanting in many ways. Norton points out that the Teller Institute was “plagued with runaways,” though those students stories are not told in the detail they deserve. Students at the Teller Institute did hard labor. They dug the cesspool that stood near the school, and they lived under the supervision of parsimonious administrators seemingly far more interested in the health of the institution than its students. In one particularly revealing story, a federal agent at Fort Defiance asked the Teller Institute superintendent to return Navajo students to their home. Their parents wanted them back. The superintendent reluctantly gave in, but provided the students with train fare that got them only as far as Durango. According to Norton, they had to ride bicycles to get them the final 150 miles home. Norton’s report would be so much more valuable with more stories of this sort. I want to learn about awful administrators, but also about the students and their families.

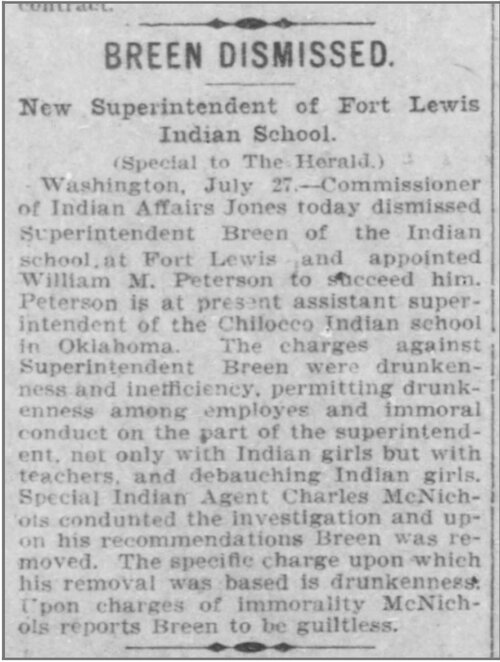

The Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School received students from its opening in 1892 until 1909. In total, nearly 1100 students passed through its doors, drawn from twenty different Indigenous communities and nations. Like the Teller Institute, it faced significant turnover in its administration. The superintendent who served the longest was the school’s most notorious. Dr. Thomas Breen oversaw Fort Lewis from 1894 to 1903. A serial abuser of women and girls, according to contemporary reporting in Denver newspapers, his tenure was one prolonged scandal. According to Norton, “the story of the Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School under Breen and the failure of the federal government to protect Native children is a microcosm of the deep neglect that was visited on the children by the government throughout the entirety of the school system”(67).

Again, this point is asserted rather than demonstrated. Throughout, the Colorado report is cursory in its coverage. The author makes reference to archival collections, but because she does not quote from them, her arguments are not well-supported and powerfully presented. We learn little about the tuberculosis outbreak at Fort Lewis, or the damage done there by infections of trachoma, even if we know, thanks to the fantastic work of Professor Michaela Morgan Adams, that parents forcefully resisted the boarding schools, advocated powerfully for their children, and served as powerful and compelling critics of institutions that failed to care for students.

Similarly truncated is the chapter that covers the “children who did not return home.” Ever since the discover of 200 unmarked graves outside a residential school in Canada, this has been viewed as the most important driver of new interest in the history of boarding schools, and efforts to uncover truth in the name of state’s achieving reconciliation. Thirty-one children died at the Fort Lewis school during the 18 years it was open, thirty-seven at the Teller Institute, a figure which included the daughter of the school’s carpenter, a teacher, and a former student.

Norton mentions that the surviving records for the schools are in poor condition. They are, presumably, difficult to read and work with. Nonetheless, I wish the History Colorado team had done more. Boarding schools were institutions, and the institutional component is the easiest part of their histories to research. Schools were bureaucracies, and they generated paper: records historians can use to reconstruct precisely how they worked. But they were also the site of dramatic moments in Indigenous peoples’ lives. Students who went to boarding school list among their most powerful memories seeing their parents crying, even though at the time they did not understand the source of those tears. Students unquestionably suffered from home sickness, loneliness, privation and abuse. The consequences of the treatment they received may continue to plague their families, a problem scholars now refer to as “intergenerational trauma.” But neither students, nor their families, stood by idly. They engaged these institutions, insisted that their children receive just treatment, and called for their return when they felt things were not going well. In our efforts to recount the history of boarding and residential schools we must make sure we place front and center the Indigenous peoples who survived those institutions the federal government dedicated to their destruction. We make choices about the stories we tell, and as scholars we need to own that. And because we want to persuade the millions of Americans who know nothing about these institutions to understand the injustices that happened there, and the ambivalent feelings many Indigenous peoples express about the boarding school experience, we need to tell these stories effectively and powerfully. We should not shy away from the darkness, and not hesitate to tell the stories of resistance and accommodation to these institutions in all their wondrous complexity.