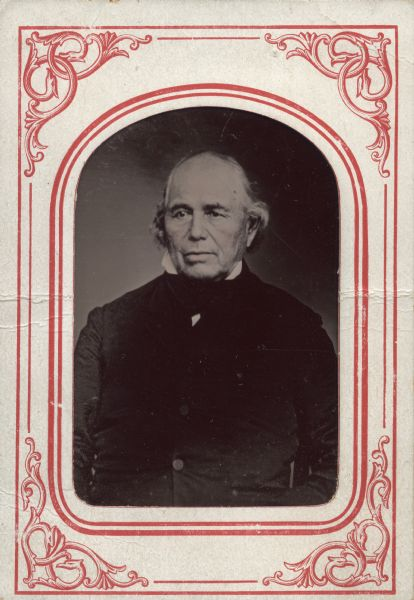

About ten years ago, I completed a biography of Eleazer Williams, who played an instrumental role in the history of Oneida dispossession in New York, and Indigenous dispossession generally. He was a fascinating figure. I discovered Williams while conducting research for the United States Department of Justice in the Oneida Land claim. The Oneidas claimed that the state of New York had violated the Federal Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts when it purchased Oneida lands. New York counter-sued the United States, arguing in essence, that if New York did indeed steal Oneida land, the United States had allowed that process to happen. I tell that story in great detail in Professional Indian: The American Odyssey of Eleazer Williams. Today, as I resume this series of posts about stolen land in New York, I will focus one of the most indelible characters in the story, at the end of his career, when he began touring the Northeast, claiming that he was the Dauphin, the long lost child of Marie Antoinette. Much of what is included in this post derives from some talks I gave based upon that book. This is a longer post than usual. I hope you find in it something of value.

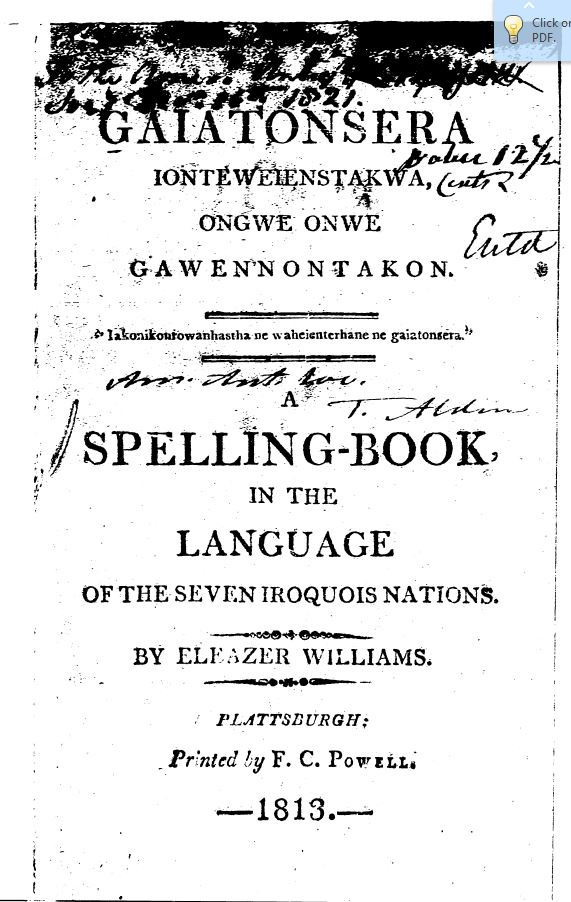

Eleazer Williams once had been well-known for his success as a missionary among the Oneidas in New York. Federal officials involved in the development and implementation of American Indian policy, and the land speculators in league with them who coveted Iroquois land, appreciated the assistance he gave them in “removing” the New York Indians to new homes in Wisconsin. For a brief period they too accorded him a great deal of respect. He was something of a celebrity in the 1820s, and knew personally several secretaries of war, commissioners of Indian Affairs, and Presidents of the United States. But that was in the past. By the end of the 1830s, Williams, the Mohawk great-grandson of that unredeemed Puritan captive Eunice Williams, had fallen upon hard times. The Oneidas who relocated to Green Bay at least in part at his urging cast him out of their community. They felt that he did not pay adequate attention to their religious concerns and they believed that he remained too close to those who clamored for the lands they had left.[1] Those Oneidas who remained behind in New York for the most part felt little affection for him as well. In addition to falling out of favor with the native communities he had ministered to, he was deeply in debt, hounded by those who sought to attach what little property he still had. And his marriage had grown cold. After the death of an infant child in the spring of 1838, Williams spent little time with his heart-broken wife. He advised her to accept that the child’s death was the will of God, that it was the Christian’s duty to carry on in the face of tragedy, but he could not fill the great void that remained. He had, it seems, little else that he could say to her, so he stayed away. He visited his unwelcoming home in Wisconsin only on occasion, and spent much of his time shuttling back and forth between the nation’s capitol where he continued to pursue various schemes in behalf of Indians he claimed to represent and for himself, and the Mohawk reserve at St. Regis (Akwesasne) where he hoped to revitalize his flagging clerical career by establishing a mission school and an Episcopal Church. It was on one of these journeys, in the fall of 1841, Williams claimed, when he first learned of his royal pedigree, that he was no mere Indian but rather the long, lost son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Writing the history of a man known by his most charitable biographers as a “charlatan,” and by others as “a fat, lazy, good for nothing Indian,” a traitor to the Kanienkehaka, and an “incubus” who “was the most perfect adept at fraud, deceit, and intrigue that the world ever produced” certainly presents many challenges.[2] Eleazer Williams, that distant descendant of an unredeemed Puritan captive, veteran of the War of 1812, missionary to the Oneidas, putative leader in the movement of the New York Indians to new homes in Wisconsin and, ultimately, a man who claimed to be the Dauphin was, among other things, a liar and a teller of tales. Sorting out truth from fiction in his unquestionably important life is simply not always possible. The purpose of this essay is to explore one part of this complicated life and Williams’s most notorious tale—that the humble missionary from Kanawake was no Mohawk but the child of a king and a queen—and the racialized debate it generated.

François-Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Marie d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville, left Buffalo on 13 October 1841 aboard the steamboat Columbusbound for Green Bay. Newspapers reported on Joinville’s progress. When the Columbus arrived at Mackinac, several days later, Eleazer Williams boarded. Williams learned from the captain, he claimed later, that Joinville had asked about him several times. His desire to meet Williams, it seemed, was relentless. When they finally met, one observer recalled, “the Prince received Williams with an embrace and went with him to his cabin where the two sat in close conversation until a late hour, about two in the morning.”[3] Whether Joinville sought out Williams because of the latter’s fame as a missionary, or because Joinville had heard that Williams, “skilled in Indianology and acquainted with the Northwest,” might serve as a useful tour guide, or because, as Williams claimed, of his ties to Joinville’s family, or not at all is in the end impossible to tell. Joinville’s secretary denied that the encounter took place and Eleazer Williams left the only account of the lengthy conversations that reportedly followed their meeting.[4]

On board the steamboat, Williams remembered, Joinville approached him with unstinting courtesy. Joinville asked Williams if he would “not be intruding too much upon your feelings and patience were I to ask some questions in relation to your past and present life among the Indians.” So said Williams, recalling in 1851 the exact words of a conversation a decade after it had taken place. He and Joinville spoke of the history of the French in America. They spoke about missions to the Indians, of their improvability, and of Christianity. Joinville was polite and interested, but had something else on his mind. At last he came to his point. The son of Louis XVI, Joinville told Williams, to avoid the terrible fate that befell his parents during the French Revolution, had been secretly carried across the Atlantic by Royalist sympathizers and deposited among the Iroquois in Canada. Thereafter he disappeared, and had not been heard from since. Sizing up Williams, Joinville believed that at long last he had found the Dauphin.[5]

Williams claimed that this startling news left him devastated, that “it filled my inward soul with poignant grief and sorrow.” He continued,

The intelligence was not only new but awful in its nature, to learn for the first time that I am connected by consanguinity with those whose history I had read with so much interest, and for whose sufferings in prison and the manner of their deaths, had moistened my cheeks with sympathetic tear. Is it so? Is it true, that I am among the number who are thus destined to such degradation–from a mighty power to a helpless prisoner of the state? From a palace to a prison and dungeon—to be exiled from one of the finest Empires in Europe and to be a wanderer in the wilds of America—from the society of the most polite and accomplished countries to be associated with the ignorant and degraded Indians?[6]

If it was God’s will that Williams be cast from his seat at Versailles to live with savages, Joinville in 1841 had something very different in mind. After finding the Dauphin at long last, he wanted Williams to disappear once again, but only after he signed a document formally abdicating any claims to the throne of France. Williams, with a dramatic flourish, refused. In his journal for this period, which he likely fabricated entirely, Williams reflected on this series of events. He was, he claimed, overwhelmed. On the last day of October he recorded that “I am [an] unhappy man, and in my sorrow and mournful state, I would often with a sigh cry out, like David, O my Father, O my Mother.”[7]

Though the Prince de Joinville later claimed that this conversation never took place, other observers in Green Bay, perhaps eager to claim some connection to royalty, recalled events that seemed to support elements of Williams’s story. According to a very elderly Wisconsonian named Mary Allen, her grandmother met with Joinville during his visit to Green Bay. The Prince, Allen said, asked for her grandmother’s opinion of Eleazer Williams. She said that she believed that Williams “had no Indian blood in his veins.” This answer may have confirmed what Joinville already believed, if Williams was right about their encounter. Then, according to Allen, she proceeded to tell Joinville a story that “staggered” the Prince. Her husband collected engravings, she said. One evening, she recalled, Williams leafed through the collection. Williams stopped at a face that seemed to him disturbingly familiar. Williams seemed stunned, agitated, as if he had seen a frightening ghost. Williams “arose to his feet, trembling from limb to limb; the cold perspiration was pouring down his face; he caught hold of my chair as a support.” It was a compelling act that Williams repeated on a number of occasions. Allen’s grandmother seems to have bought it in its entirety. Williams bade his hosts good night, with tears in his eyes. Allen’s grandmother looked at the engraving that had so struck Williams and found that it was “Simon the Jailer,” the sadistic torturer of the child Dauphin.[8]

Yet if Joinville’s message troubled Williams, and images of his tormenters haunted him, he did little about it at the time. Over the course of the 1840s he continued to struggle with the financial problems that had plagued him for over a decade. He still preached on occasion. Small fringe groups of Oneidas in New York and Wisconsin on rare occasions invited him to visit them. He traveled frequently, an Indian man-on-the-make in Jacksonian America.[9]

Despite these rare invitations to preach, Williams’s clerical career was in a shambles and, in 1848, after the “melancholy death of my reputed father” at Akwesasne, the Dauphin story re-emerged.[10] In February of that year, Williams wrote, he had learned that “a respectable French gentleman, by the name of Belanger,” had died in New Orleans, but not before he “revealed a secret” he had carried with him for many years. Belanger, Williams reportedly learned, had confided to his closest friends, on his deathbed, that the “Reverend Gentleman who bears the name Eleazer Williams . . . was really and truly the son of Louis XVI, King of France, and that he was the principal agent, under the patronage of the Royalists, in rescuing the Dauphin from the Temple in June of 1795, and whom, he had placed among the Iroquois Indians at the North.” In a strangely ambiguous note to his wife, written in September 1848, Williams wrote that “the long talk of my foreign descent, is now too true,” a fact that for him had “caused a great grief.” If he sent the letter, and if she received it, no response exists. Williams’s wife never expressed any interest in his claims to be the Dauphin.[11]

Once again, Williams was the original source of information on the role reportedly played by Belanger in his rescue from a French dungeon and secret placement in the wilds of Canada. Williams asked one newspaper editor to publish an essay he wrote stating that “an heir to the throne of Louis XVI is still living” and “that the youth [Belanger] had put among the Indians at the North was truly and really the son of Louis XVI.”[12] Williams met with the occasional reporter passing through Green Bay, when he was there, convincing one that his “appearance, manners, conversation, and mode of expression are not those of an Indian, but of a Frenchman,” and another that not only was he now “a chief of the St. Regis Indians” but that his features “were not only unlike those of an Indian, but were directly in opposition to them.”[13] He told friends in the Connecticut River Valley that he did “not know what to believe in regard to his origin,” and that he could not tell “whether he is the Dauphin or not,” but he did nothing to dissuade them when they “compared his features with the engraved heads of Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, and found a striking resemblance.”[14]

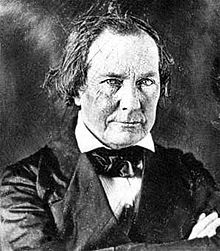

It was still a small story, spreading no further than the narrow scope of wherever Williams happened to be at the moment. Only after Williams met the Rev. John H. Hanson did a broader audience begin to wonder if there was indeed “a Bourbon among us.” A minister for a brief time at Waddington in St. Lawrence County, a short distance upriver from St. Regis, Hanson met Williams for the first time in the fall of 1851. With his assistance, one critic noted, Williams was transformed “from a secret, surreptitious pretender into an open vindicator of his royal parentage.”[15]

Their first encounter took place in northern New York on the Ogdensburg Railroad to Rouse’s Point, and then on a steamboat that carried them south along the shores of Lake Champlain. Hanson claimed a perfect familiarity “with the Indian lineaments and characteristics” and “after attentively comparing his appearance with that of his reputed countrymen,” wondered how “any attentive observer should ever have imagined him to be an Indian.”[16] Hanson asked Williams “if he believed the story of his royal origin,” and asked Williams what he remembered of his childhood. Williams, of course, claimed to remember nothing before the age of thirteen or fourteen when, after hitting his head on a rock after diving into Lake George, memories started coming back to him: Frenchmen visiting his “reputed” father in 1795 or 1796, for instance, and shedding “an abundance of tears” over the poor child who had suffered so much.[17]

Hanson asked about Williams’s mother. Surely she could shed some light for him on the story of his royal descent. Of course Williams anticipated the question. It required little imagination to expect Hanson to ask him about his “Indian” family. Williams indeed had asked her several years after his encounter with Joinville, he told Hanson. When he met her at Kanawake, however, Williams “found that many of the Romish priests had been tampering with her, and that her mouth was hermetically sealed.” They threatened the elderly woman with excommunication should she reveal to Williams anything about his origins and so, Williams said, “my efforts to extract anything from her were unavailing,” and “her immovable Indian obstinacy has hitherto been proof against every effort I could make.” It was a masterful answer, or at least masterful enough to convince the entirely guileless Hanson, combining the vigorous anti-Catholicism popular in Protestant New York with stereotypes of the “stolid” and savage “sqauw drudge.”[18] Williams then told Hanson in detail of his meeting with Joinville a decade before, and of the death of Belanger in New Orleans.[19]

They spoke for some time as they sat on the deck of the steamship that carried them south along Lake Champlain. “You have been talking,” Williams told Hanson, “with a king tonight.” He invited Hanson to join him in the parlor downstairs from where they had been sitting. There Williams took from his valise some miniatures and a daguerreotype. One of the miniatures depicted his wife at the time Williams married her. In one of the few truthful things he said that evening, Williams recalled how he had left her alone in the west. He did not mention the child he left behind with her, or the wreckage left after the infant’s death thirteen years before. He did not dwell upon her. He moved on, showing Hanson another miniature that depicted his “mother,” Marie Antoinette. He showed Hanson the daguerreotype as well, in which he posed with “a broad band fastened by an ornamental cross passed over his shoulder as worn by European princes.”[20] And he showed Hanson an ornate dress that he carried with him, a useful prop that completely convinced the credulous Hanson, that Williams claimed had been worn by his mother. Indeed, Hanson recalled, he felt pleasure “in believing in the truth of the memorials of the past,” and he could not, he wrote, “envy the critical coldness of one who would ridicule me for surrendering myself, under the influence of the scene, to the belief, that the strange old gentleman before me, whose very aspect is a problem, was son to the fair being whose queenly form that faded dress had once contained.”[21]

Hanson knew little of critical coldness. That much was clear. And Williams was not finished. He gave Hanson a copy of what he claimed was his journal for the years 1841 and 1848. He showed Hanson the scars on his knees, over his left eye, and on the right side of his nose, marks entirely consistent he said with the illnesses and injuries the Dauphin reportedly suffered while imprisoned by Simon the Jailer.[22] Hanson listened to all that Williams told him. He looked at the evidence Williams presented and believed it all. But in the end the most compelling piece of evidence was, for Hanson, not Williams’s stories and fragmentary memories, but Williams himself.

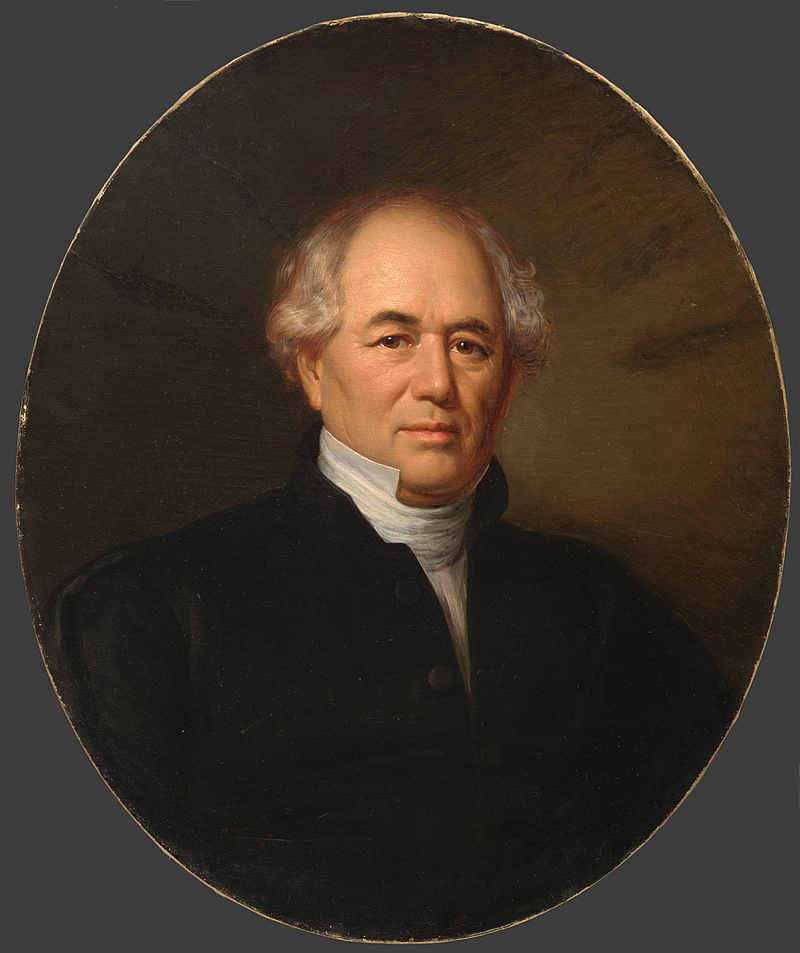

Hanson, as their journey continued, “proceeded to scrutinize more closely the form, features, and general appearance of Mr. Williams.” Hanson found him “an intelligent, noble-looking old man, with no trace, however slight, of the Indian about him except what may be fairly allowed for by his long residence among Indians.” He spoke Mohawk and English, which Hanson thought he pronounced perfectly, but he did not seem to be an Indian.[23] Williams’s “manner of talking,” Hanson wrote, “reminds you of a Frenchman, and he shrugs his shoulders, and gesticulates like one.” What Hanson knew about how Frenchmen shrugged, and the manner of their gesticulation, remains murky, but he was entirely convinced by Williams. Wrestling with the language he needed to describe what he saw in Williams, Hanson claimed that his friend had

the port and presence of an European gentleman of high rank, a nameless something which I never saw but in persons accustomed to command; a countenance bronzed by exposure below the eyebrows; a fair, high, ample, intellectual, but receding forehead; a slightly aquiline, but rather small nose; a long Austrian lip, the expression of which is of exceeding sweetness when in repose; full fleshy cheeks, but not high cheek bones; dark, bright, merry eyes of hazel hue; graceful well-formed neck; strong, muscular limbs, indicating health and great activity; small hands and feet, and dark hair, sprinkled with gray, as fine in texture as silk.

In Williams’s carriage, his demeanor and in the shape of his body, Hanson found his most compelling evidence that he had indeed encountered a European of highly-elevated status. Williams, Hanson believed, was no Indian and he may well be the Dauphin.[24]

Hanson laid out his argument in an essay that appeared in Putnam’s Magazine early in 1853. Reciting the tales that Williams earlier had told him, Hanson argued that the Dauphin did not die during his imprisonment in 1795, that he was carried to North America “to the region in which Mr. Williams spent his youth,” that Eleazer Williams was not an Indian, and therefore he was in fact Louis XVII.[25] Hanson, according to the New York Times, asserted that his evidence was “irresistible” and that he stood willing to stake “his reputation as a man of common sense and common discernment on the issue.”[26]

A number of critics were willing to take that bet. Putnam’s, one pointed out, liked to publish sensational stories, though few of them were as absurd as Hanson’s.[27] Williams, another pointed out, was eight years too young to be the Dauphin and, besides, his mother, who certainly knew better, gave a deposition in which she stated that Eleazer Williams was her fourth child, and “that her son Eleazer very strongly resembles his father Thomas Williams; and that no person whatever, either clergymen or others, ever advised her or influenced her, in any manner, to say that he was her son” (which of course Willaims and Hanson said was evidence that clergymen and others had done just that).[28] Some were willing to concede that Eleazer Williams was not an Indian but, rather, “the best of human kind.” Still, he was an imposter.[29] Those who believed that Williams was an Indian on occasion felt sorry for him. “The true pity,” wrote one observer of the controversy, “is that Mr. Williams has permitted his confidence to be diverted from his truly honorable ancestry, and from the high office to which he has been ordained, to dream of descent from vulgar kings.” The passive verb was important: as an Indian, Williams could not possess the requisite sophistication and cunning to compose so complicated a tale. Williams should be proud of his descent from Eunice Williams.[30]

Hanson responded to his critics, gathering additional evidence, challenging his critics’ claims, exposing their biases. But he also took Williams for examination by an impartial panel of medical experts in New York City, an omen of where this debate was headed. Hanson’s doctors found that Williams was neither crazy nor an Indian, though nobody had suggested publicly that he was the former. One physician concluded that Williams had “a lofty aspect, strongly marked outline of figure, obviously European complexion, and,” consistent with the illnesses of the imprisoned Dauphin, “a slight tinge of scrofulous diathesis.” Another found that

The physical development of Mr. Eleazer Williams is that of a robust European, accustomed to exercise, exposure to open air, and indicative of the benefit of a generous diet, and a healthy state of the digestive organs. He might readily be pronounced of French blood. His general appearance and bearing are of a superior order: his countenance in repose is calm and benignant; his eyes hazel, expressive and brilliant, and his whole contour, when animated, indicates a sensitive and improvable organization . . . . There are no traces of the aboriginal or Indian in him. Ethnology gives no countenance to such a conclusion. The fact is verified by anatomical examination, and no unsoundness of mind or monomania has been manifested by any circumstance evinced in communication with him.

Hanson included this and other medical testimony in his lengthy biography of Williams, The Lost Prince.[31] Indeed, Hanson had Williams examined also by Dr. H. N. Walker of Hogansburg, New York. Walker told Hanson, in a letter published in The Lost Prince, that Williams had “no ethnological connection with the St. Regis Indians, nor with any other Indians I have ever known.” If indeed Williams was an Indian, “it is in the absence of all those ethnological signs discernable in form, features, texture of the skin, hair and other similar tokens well-known to the profession, which, as far as my observations and information extend, are considered decisive.”[32]

As this debate unfolded in newspapers and magazines, Williams himself struggled to re-establish his clerical career. Deeply in debt, his efforts to obtain pensions for his service and his father’s service during the War of 1812 had produced nothing. Neither had Williams managed to obtain payment on promises made him in the 1838 Buffalo Creek Treaty due for the assistance he had provided the Ogden Land Company in its efforts to eject the New York Indians to new homes in the west. And claiming to be the Dauphin did not yet carry with it any sort of paycheck.[33]

Williams, in 1849, hoped to return to Wisconsin with the support of the Episcopal Church to minister to the Oneidas, but the relocated Indians wanted nothing to do with him. “We are persuaded that while among us,” wrote several Oneida chiefs, “his aim was not to benefit us but to destroy us as a nation.” Williams, they wrote, “watched over us more like a wolf ready to seize upon and devour us than as a shepherd whose care would be to protect and shield us from danger.” Williams, the chiefs made clear to the Episcopal establishments in both Wisconsin and New York, was not welcome. He was a liar who would say anything to benefit himself. He openly disrespected the church and “laughed” at it “as a cold and lifeless body incapable of imparting more than the form of godliness to its members.” They did not consider Williams “worthy to serve as a minister of the Church in any place.”[34]

Williams, and a small number of non-native allies, mounted a defense against these charges, asserting that they stemmed from the hard feelings of his clerical rivals and factionalism among the Oneidas. There are elements of truth in each of these claims, but his arguments left the diocesan officials unmoved. [35] Jackson Kemper, bishop in the western diocese, viewed Williams as an incompetent and self-aggrandizing missionary who had neglected his duties and mismanaged church resources. Kemper, in announcing to Williams that he could not consent to his return to service in Wisconsin, told him that “I have often deeply mourned that a clergyman of your talents and attainments should have utterly wasted the best years of your life.” Find something else to do, Kemper wrote, in a diocese where you are welcome.[36]

And that is what Williams did. Through his secretary, Williams informed the Standing Committee of the Episcopal Diocese in New York that he intended to resume his work at St. Regis. Lest they think of this as a run-of-the-mill mission enterprise, the Committee learned that “at this moment there is a great interest taken in the welfare of your humble missionary, among some of the most respectable characters in America, England, France and Austria.” Williams’s project at St. Regis, his secretary suggested, was a mission worth supporting.[37]

Before the Episcopal Diocese of New York could support Williams in his effort to establish a school among the Mohawks, however, its leaders needed to sort out what happened in his relationship with the Oneidas and whether he was worth backing financially. Protestant missions struggled at St. Regis, and many in the community—“the most venal and heartless set of beings in human shape, ever debauched by a low-bred priest”—maintained ties to the Catholic Church.[38] The letters preserved in Williams’s file in the archives of the Episcopal Diocese of New York reveal the lengths he went to in order to gain its support. By 1851 he had, he said, “established a school in the eastern part of their reservation, where the Indian Children to the number of 22 are taught in the rudimental books of the English education.” With church support, he could establish the Protestant Episcopal Church amongst the Mohawks. But he needed money. He described his hardships. He requested letters from supporters to speak for his efforts.[39] He attempted to refute the many charges made by his critics.[40] Ultimately, these critics relented, as long as he did his work in New York and not in Wisconsin. Jackson Kemper recommended that the New York diocese “try him again, for he has talents.” Kemper had heard of Williams’s claim that he was the Dauphin. He knew these beliefs were “unfounded,” and did not know why Williams was making these claims, but Kemper thought these “notions relative to France” will “neither injure him nor impair his usefulness.”[41]

Williams won from the Episcopal Diocese of New York its blessings to carry on his work among the Mohawks. He remained, however, in a straitened condition, constantly short of money, and he received little by way of a stipend.[42] According to A. G. Ellis, Williams’s protégé at the Oneida mission in the early 1820s and, much later, his harshest critic, Williams conjured the Dauphin tale “to give him notoriety, to repair his damaged fortunes, and enable him to re-enter those high circles in which he has for so many years failed to appear.” Williams clearly used the Dauphin story in a calculated and deliberate manner to resuscitate his moribund clerical career.[43]

Williams wrote letters. In a rare note addressed to his wife, with whom he seldom communicated, he announced that he was returning to St. Regis. He asked her whether he should continue to serve as “a humble missionary or a king, in a splendid court and at the head of a mighty empire.” She does not appear to have cared what he did. He did not present the Madam R. V. Hotckiss, a wealthy evangelical reformer, with a choice. “Although royalty and a family title may be connected with your correspondent, and these may sound high with the men of the world,” he wrote, he “would view his station to be sufficiently honorable, when it is said to be an Indian missionary.” He would set aside his claims to the throne and return contentedly to his mission, which he could do more easily and with more effectiveness if she contributed to the funds he had collected “for the building of the church.”[44]

He spoke frequently, visiting churches throughout the northeastern United States. He toured to raise money to support himself and his missionary enterprise, to pay for the construction of a church that he would never build and the publication of the Book of Common Prayer in Mohawk, a task that he did complete in 1853. The faithful and the curious came out to see the Dauphin on tour. They responded with alacrity, according to most accounts, to Williams’s call for donations. Indeed, Williams reported to his old antagonist Jackson Kemper that “my appeal to the churches in your Atlantic cities has been responded well to my satisfaction.”[45]

We do not have a complete record of what Williams said to these audiences, but by piecing together a number of accounts, along with fragments found in Williams’s papers, it is possible to arrive at some sense of how he constructed his appeal. Certainly he spent some time describing the state of his mission. “I have from 18 to 25 scholars,” he told one audience, “who have made a good progress in the first rudiments of an English education.” Some philanthropists had provided funding but he could do so much more with additional support. He had yet to build the church, he said, and the inadequacy of his schoolhouse was made clear during the brutal northern New York winters. With students eager, and their families supportive, all that was required was the assistance of Christians to bring this mission to fruition.[46]

In Troy, New York, Williams preached on Titus, Chapter 1, verses 2 and 3. He spoke to his audience about the hope of eternal life, God’s precious gift to mankind. And then, according to the Troy Daily Traveler, Williams “proceeded to address his hearers in behalf of the American Indians.” Employing the well-worn image of the vanishing American, Williams appealed to the consciences of his audience. The Indian, he said, was once “the sole possessor, the undisputed Lord” of a “vast domain” which included “the broad lands which you now enjoy.” The Indians’ losses would be the white man’s gain. When “the broad Atlantic bore upon its bosom . . . the ships of another nation, freighted with the subjects of a foreign prince,” the Indians met them “upon the beach,” where the newcomers stood helplessly, with “the ocean behind, and the vast wilderness before them.”[47]

The newcomers came with the “avowed object” of reclaiming “the savage from heathenism to Christianity—to bring him from the darkness of barbarous life, to the light of Christian truth.” It had not worked out very well. “Mark the history of the succeeding years,” he said, “to see the Indian fading away before the aggressive march of the white man,” the “moral and physical degradation to which he was led.” It was the white man who bore responsibility. It was he, Williams continued, “who pressed the accursed bowl to his lips,” he “who added the vices of civilized life to those of savage existence,” and he “who had proclaimed the gracious design of bringing the savage people to the light of glorious gospel” while robbing the Indian “of the possessions, and for the products of his toil gave him in return the worthless beads and tinsel trappings, which swelled the coffers of the white man’s cupidity and avarice.” All of Native American history, Williams told his audience, was “a history of wrong.”[48]

Williams kept moving. He preached in Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and spent a considerable amount of time in Philadelphia. He made his appeal for financial support in many churches. Philadelphians, for instance, might have heard him preach “in several of our city churches” and audiences everywhere he went were “much impressed with the modest and forcible way in which this veteran missionary presented the claims of a much injured people upon the sympathies of American churchmen.”[49]

Yet many of those who attended his presentations and dropped their coins in the collection plate were drawn in more by Williams’s claim to be the dauphin than by a desire to support missionary activity among the Mohawks at Akwesasne. Certainly those who promoted Williams’s appearances employed the story “of the Lost Prince” and “a son of the late Louis XVI” who was now “an humble missionary among the Indians, our red brethren of the forest,” to generate interest in their churches. Reverend Williams, the Middletown, Connecticut Sentinel and Witness reported early in 1855, was “believed to be the son of the unfortunate Louis XVI and his equally unfortunate Queen, Marie Antoinette.” That a humble missionary like Williams, “descended from the race of kings, of more than three score in number, should, in the providence of God, in a foreign country be an ambassador of the King of Kings, to the feeble and scattered remnants of those who were once themselves, the lords and kings of an immense domain, is certainly a consideration fraught with material for reflection and interest.”[50] But Williams himself appears to have said little about his parentage, and this frustrated some of those who came to hear him preach. They wanted him to address specifically where he stood on the question of his asserted royal identity. Williams clearly had used the notoriety to generate interest in his missionary activity. However, as the Washington, D. C. Daily National Era pointed out in the spring of 1854, “Mr. Williams either does or does not profess to believe that he is the son of Louis XVI.” He should take a stand and do so publicly. “If he does, he should say so; if he does not, he should not permit any one, whether to give him or his mission éclat, or for whatever purpose, to place him in an equivocal position before the world.”[51]

Some in those audiences found the notion that Williams was the dauphin entirely unbelievable. But they did not base their skepticism on the obvious problems with his story: Williams was too young by a few years, lacked any evidence to support his ties to the French, and could never provide any evidence to account for its utter implausibility. Instead, they focused on a variety of “racial” characteristics that to them seemed to demonstrate that Williams was an Indian or, at best, a half-breed, both of which of course disqualified any claim that he might be the Dauphin.

Williams conducted his missionary appeal at the tail end of a period where race science had come to define native peoples of the “American race” as inferior to “Caucasians.” Though the environmentalism of earlier eras did not disappear entirely during the Antebellum era, it certainly had come under attack. Charles Caldwell, for instance, after examining the heads of the members of an Indian delegation visiting the nation’s capitol, asserted that “the native bent” of white people was towards civilization, while with Indians, the reverse was true. “Savagism, a roaming life, and a home in the forest, are as natural to them, and as essential to their existence, as to the buffalo or the bear. Civilization is destined to exterminate them in common with the wild animals among which they have lived, and on which they have subsisted.” The only hope for their survival was cross-breeding with white people. “By the requisite means, half- and quarter-breeds and those having still less of the Indian in them, may be educated and rendered useful members of civil society.”[52]

These pseudo-scientific inquiries led rather mechanically to lists of characteristics that defined the different races. Samuel George Morton, an enthusiastic collector of human skulls, the measurement of which formed the basis of his science, concluded that American Indians were intellectually and physically inferior to Caucasians.[53] If Caucasians, for instance, possessed “naturally fair skin,” hair that was “fine, long and curling and of various colors,” with a skull “large and oval” and a face “small in proportion to the head, of an oval form, with well-proportioned features,” a “brown complexion, long, black, lank hair, and deficient beard” marked “the American race.” In Indians, Morton wrote, “the cheek bones are large and prominent, and incline rapidly toward the lower jaw, giving the face an angular conformation.” The Indians’ “upper jaw is often elongated and much inclined outwards, but the teeth are for the most part vertical. The lower jaw is broad and ponderous, and truncated in front.” The teeth are also very large, and seldom decayed,” Morton continued, “for among the many that remain in the skulls in my possession, very few present any marks of disease, although they are often much worn down by attrition in the mastication of hard substances.” Their hair was always straight and black, and among the Indians, “no trace of the frizzled locks of the Polynesian, or the wooly texture of the negro, has ever been observed.”[54]

Morton could read the skulls and deduce more than mere physical characteristics. “The bold physical development of the American savage,” he wrote, “is accompanied by a corresponding acuteness in the organs of sense.” Indians were “vigilant,” a product of “the constant state of suspicion and alarm in which the Indian lives.” They spoke “in a slow and studied manner, and to avoid committing himself he often resorts to metaphorical phrases which have no precise meaning.” They employed subterfuge against their enemies, who they pursued relentlessly. The Iroquois especially, Morton said, “possessed all the other Indian characteristics in strong relief.” They “paid little respect to old age; they were not much affected by the passion of love, and singularly regardless of the connubial obligations; and they unhesitatingly resorted to suicide as a remedy for domestic or other evils.” The Iroquois, he said, “were proud, audacious, and vindictive, untiring in the pursuit of the enemy, and remorseless in the gratification of their revenge.”[55]

So Williams’s critics seldom dismissed his claims on the basis of their implausibility, or because they thought that the missionary was deluded or insane or nuts, but because in racial terms Williams did not seem to evidence any of the characteristics they associated with noble European birth. The author of a piece that appeared in the New York Herald, for instance, who wrote under the pseudonym St. Clair and who claimed to have met Williams several years before, argued that “no man acquainted with our aboriginal race, and who has seen Mr. Williams, can for a moment doubt his descent from that stock.” Williams was an Indian, and “his color, his features, and the conformation of his face, testify to his origin.”[56] A. G. Ellis said that he was “unquestionably a half-breed Mohawk Indian, having all the distinctive features of the race: the black straight hair, the black eyes, the copper color, and high cheek bone; and all who knew him when young remarked this.” Years later, Ellis would suggest that Williams was “dark enough for a ¾ Indian.”[57] C. C. Trowbridge, who knew Williams in Wisconsin, laughed at the Dauphin story. Williams “had all the peculiarities of a half-breed Indian, as undoubtedly he was . . . .If he had been otherwise, mentally or morally, his hair and complexion would have stamped him as of mixed savage and civilized blood.”[58]

Science came readily to the assistance of those who doubted Williams’s claims to be the dauphin. Peter A. Browne, for instance, a race expert in Philadelphia who could “ascertain the race of an individual by the hair upon the head, with as inevitable certainty as a phrenologist can determine character by bumps,” concluded from his examination of Williams that “there is a difference in the diameter of the hairs of Mr. Williams,” and that “some are oval, some cylindrical,” and that “therefore he is a cross of Indian and white” and “consequently he is not the Dauphin.”[59]

Many others disagreed, but they too framed their views in terms of Williams’s racial characteristics. Hanson asserted that “there are certain characteristics of the Indian race which are all but indelible, and appear after the lapse of centuries, even on the cheek of beauty.” Hanson looked at Williams closely and knew him well. “When the fact of origin has died into a tradition,” he wrote, “you can mark the red blood coursing with a duskier hue beneath the mantling blush brought from other climes, and imparting fixity and palor to its softness. Skin, hair, craniological formation in the closer degrees of affinity, present ready and infallible tests.”[60]

And so it went. A correspondent from a New York French-language paper, the Courier de Etats Unis, found that Williams did not look like an Indian and that with him, “the forehead and the lower part of the face show a great analogy to certain physiognomies of” the Bourbons. Williams reminded the writer “entirely of Louis XVIII, whose countenance has remained perfectly fixed in our memory.”[61] Another New Yorker reported that although Williams’s complexion was “rather dark,” having “become somewhat bronzed by exposure,” his features were “heavily moulded, with the full Austrian lip, eyes dark hazle, and hair, dark, fine, and curling, somewhat sprinkled with gray.” Williams was of medium height, full-chested, broad across the shoulders, “and inclined to emboument, which is a well-known characteristic of the Bourbons.” A correspondent from a Troy, New York, newspaper concluded that some thought Williams was of mixed racial descent, but he could find no evidence of that himself. In Williams’s features “we could trace no works of the Indian. They are decidedly European.”[62]

Artists, familiar with the Bourbons, thought Williams looked about right to be a part of the family. Hanson spoke with M. B. H. Muller, a pupil of David and Gros. According to Hanson, Muller “was at once struck with the remarkable likeness to the royal family of France, and identified the color of Mr. Williams’s eyes, bright hazel, with those of the Dauphin, having frequently seen authentic portraits of him in France.”[63] Chevalier Fagnani, another artist living in the United States and who was familiar with the Sicilian and Spanish Bourbons, observed that “the upper part of the face is decidedly of the Bourbon cast, while the mouth and lower part resembles the Hapsburgs.” Fagnani also thought that many of Williams’s physical gestures “were similar to those peculiar to the Bourbon race.”[64]

While in Philadelphia in the spring of 1854, Williams subjected himself to medical examination once again. The doctors—this time from the Pennsylvania College of Physicians, the Jefferson Medical College, and the United States Navy—found that Williams possessed scars consistent with those received by the Dauphin, as Hanson had claimed. Further, they found that

his skin, where it has not been exposed to the weather, is that of a pure white man. His hair is of a silken fineness and curls freely. His hands and feet, his wrists and ankles are very small, indicating an ancestry unaccustomed to any hard use of their bodily organs. His countenance and reception are peculiarly benign and gracious—totally free from the reserve and austerity of the Indians.[65]

This was another point that some of Williams’s audiences raised. Not only did he look like a European and unlike an Indian, but he did not act in ways that Indians were believed to act. In Williams’s “mental likeness,” one newspaper reported, “there is something closely allied to the best Bourbon traits,” though the paper gave its readers no sense of what those traits were. In Camden, New Jersey, Williams impressed the group who had gathered to meet with him after his missionary appeal. “Much to our surprise,” one observer wrote, “we found him easy in manners, free and agreeable in conversation, with the polished bearing of a gentleman accustomed to refined and cultivated society.” In no way, they wrote, did Williams “resemble the Indian, but in zeal for their spiritual interests and temporal welfare; and we venture to say, that of a hundred intelligent and observant men, familiar with the Indian character, visiting him without any previous intimation of his being of Indian extraction, not one would have even the most remote thought of his being of any other than European origin.”[66]

And then it was over. As Williams traveled through the Northeast, preaching in several cities, newspapers reported on his progress. He preached at every Episcopal church in Philadelphia and in many other Protestant churches as well. Church-goers and the curious assembled to hear him speak. Many of them asked themselves the same question: was he or wasn’t he? Was Eleazer Williams the son of the King of France or an Indian from the Northern wilds? Was he white or red, civilized or savage? As those in the audience contemplated these questions, they looked closely at Williams. They watched his behavior, studied his comportment. They measured his color, his features, his hair, against what they believed to be the identifiers of “white” and “red.” They considered and calculated the fraction of Indian blood that flowed through his veins.

Interest in Williams and his past faded. As the country hurtled toward Civil War, there may have been other things to worry about than whether an Indian preacher actually had a claim to the throne of France. Williams returned to Akwesasne. His health, he said, stood “in a precarious state” owing to the poison that he claimed someone had secretly administered to him during his stay in Philadelphia. This was of course make-believe, as was the assassination attempt he appears to have staged at a Washington, DC boarding house a couple of months before his death in 1858.[67]

A small number of short trips excepted, like his final trip to Washington where he once again tried to obtain a pension for his service and that of his father during the War of 1812, Williams spent his few remaining years at Hogansburg. He lived, it seems, off of the small sum he had raised during his speaking tour, but he remained poor. His house was a hovel, sparsely-furnished, ill-equipped to combat the cold of winter. If he continued to keep his school—and the evidence that he did is less than clear—it was a small-scale and occasional operation. Catholicism retained its influence over Mohawk Christians at St. Regis, and Williams never succeeded in building the Episcopal Church he asked his audiences to support.

It has been, with historians, something of a commonplace to identify Williams as a man living “between Indian and white worlds,” and this chapter in his fascinating life, more than others, has provided evidence that Williams sought acceptance from White America. His climbing is what alienated so many of the people who knew him and so many of the historians who have studied him since. As John Demos pointed out, Williams, as the Dauphin, rejected his earlier career as a savage who had progressed and become civilized and Christianized. “Far from starting ‘savage,’” Williams seemed to be saying now “he has been born at the absolute pinnacle.” Circumstances had kept him down and now he wanted only what was legitimately his in the first place. “It was,” Demos concluded, “by any standard a bizarre turn of affairs, and, for many in the world of ‘civility,’ an unacceptable one.”[68]

Perhaps, but Eleazer Williams did not see himself as living ambiguously between two worlds. He saw himself as a catechist, a missionary, a leader, and an advocate for native peoples. He saw himself as a man wronged by many who had not appreciated all that he had attempted to do for them. His critics would have accepted these labels for him at times, but they would have added to this list a dishonest man, a faithless guardian, a charlatan and a bad debt. Williams always saw himself as an Indian, even as he used the Dauphin story to generate interest in his mission. He never doubted who he was.

Williams moved not through a hazy borderland between Indian and white worlds, but through many of the different worlds of the Iroquois in the first half of the nineteenth century. Kahnawake; the River towns and the clerical community in the Connecticut River Valley; the extended Williams family in New England; the American military during the War of 1812, and the missionary arms of the Episcopal Church. He spent time in the divided Oneida community in central New York; worked with missionaries, Ogden Land Company investors, and the United States Department of War. He ministered to the Oneida community established in Wisconsin, helping out as he could as New York Indians became pioneers. He negotiated with Menominees and Winnebagos, for the New York Indians and for himself, and interacted with the habitant communities and military officers at Green Bay—all before he reached the age of thirty. Late in his life he found himself a celebrity and the subject of a debate over his claim to be the Dauphin that found its origins in the racial science and pseudoscience popularized in the first half of the nineteenth century. If some Americans believed that Indians might be improved and through education might become productive citizens of the republic, others associated with “the American Race” certain fixed characteristics that they either did or did not see reflected in Williams’s face and in his manners. Williams himself said little directly about the debate. Others did that for him. He played his part in small gatherings, but allowed his audiences to wonder. It was all good so long as they contributed. The Dauphin, for Williams, was little more than a character he played, with some limited success, in the years before the American Civil War.

[1] Williams’s leadership role in the relocation of the Oneidas to Wisconsin has been overstated by previous historians, especially by William’s one-time protégé and eventual biographer A. G. Ellis. This story can be traced most effectively in Ellis’s “Advent of the New York Indians into Wisconsin,” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2 (1856), 415-449, but beware Ellis’s considerable hostility towards Williams. Laurence M. Hauptman has briefly criticized Ellis’s positions in a number of his more recent publications. See Hauptman and L. Gordon McLester III, Chief Daniel Bread and the Oneida Nation of Indians of Wisconsin,(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), 9-10; Hauptman, “The Gardener: Chief Daniel Bread and the Planting of the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin,” in Seven Generations of Iroquois Leadership: The Six Nations Since 1800, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008), 90-91; but not in Hauptman, Conspiracy of Interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 27. Ellis’s work has been relied upon too heavily. Ellis noted that a number of New York Indians, including Hendrick Aupuamut and Solomon Hendricks had contemplated removal well before Williams became involved. Ellis also pointed out that the Ogden Land Company placed enormous pressure upon New York Indians to leave the state for new homes anywhere in the west. Ellis’s own presentation, in other words, provides a careful reader with the evidence needed to call into question many of his assertions.

[2] Geoffrey E. Buerger, “Eleazer Williams: Elitism and Multiple Identity on Two Frontiers,” in Being and Becoming Indian: Biographical Studies of North American Frontiers, ed. James Clifton, (Chicago: The Dorsey Press, 1989), 115 (Charlatan); William Ward Wight, Eleazer Williams: Not the Dauphin of France, (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1903), 27-28 (fat, lazy); David Blanchard, Seven Generations: A History of the Kanienkehaka, (Kahnawake: Kahnawake Survival School, 1980), 278-82 (traitor); Gen. A. G. Ellis, “Recollections of Rev. Eleazer Williams,” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 8 (1879), 344, 347 (incubus and adept).

[3] Letter from Henry Caswell, dated 10 October 1857, reprinted from the Green Bay Historical Bulletin, 1 (Oct-Dec 1925) and included in the Papers of Eleazer Williams, microfilm edition, State Historical Society of Wisconsin (Hereafter EWP), Reel 1: 281.

[4] “Visitors on the Frontier,” Henry S. Baird Papers, W. S. Mss, V, Box 4, Folder 8, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, (Madison, WI); Wight, Williams, 1.

[5] Eleazer Williams, Journal Fragments, EWP, Reel 4, frame 334.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Eleazer Williams, Journal, EWP, Reel 4, frame 371; Wight, Williams, 2. J. H. Hanson, the chief proponent of Williams’s claims to be the Dauphin, responded directly and preemptively to address suspicions that Williams may have written his diary at a later date, fabricating entirely the story of his encounter with Joinville. See Hanson, The Lost Prince: Facts Tending to Prove the Identity of Louis the Seventeenth of France, and the Rev. Eleazer Williams, Missionary Among the Indians of North America, (New York: G. P. Putnam and Co., 1854), 375.

[8] Mary H. Allen, “The Lost Prince: A Reminiscence of 1830,” The Critic, (April 1900).

[9] “An Episcopalian,” to Rev. Dr. Milner, 7 March 1843, EWP Reel 2, frames 173-1074; Mary Williams to Amos Lawrence, 18 August 1842, EWP Reel 2, frames 167-169; Oneida Chiefs to Eleazer Williams, EWP, Reel 2, frame 178; Oneidas in New York to Eleazer Williams, 2 October 1848, Ibid.

[10] Eleazer Williams to Mr. Ostrander, October 1848, EWP Reel 2, Frame 198ff.

[11] Buerger, “Eleazer Williams,” 132; Eleazer Williams to “My Correspondent in Europe,” August 1849, EWP Reel 4, Frame 606; Eleazer Williams to Mary Hobart Williams, EWP, Reel 2.

[12] Eleazer Williams to Dear Sir (Rev. J. Leavitt ?) 18 March 1848, EWP, Reel 2, Frame 592ff; See also the letter dated August 1849 from Green Bay, EWP, Reel 2, Frame 606.

[13] Boston Herald, 24 October 1849; Alfred Cope, “A Mission to the Menominee: Alfred Cope’s Green Bay Diary (Part I), Wisconsin Magazine of History, 49 (Summer 1966), 318. I have not found Williams’s name on any list of Akwesasne chiefs.

[14] Christian Watchman and Reflector, 6 March 1851.

[15] J. H. Hanson, “Have We a Bourbon Among Us?” Putnam’s, February 1853; Wight, Williams, 30; Journal of the Proceedings of the Bishops, Clergy and Laity of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, Assembled in a General Convention, (New York: Daniel Dana, Jr., 1847), 247.

[16] Hanson, Lost Prince, 337-338.

[17] Ibid., 187.

[18] Hanson, “Have We?”

[19] Hanson, Lost Prince, 340-342.

[20] Hanson, “Have We?”

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] A. G. Ellis said that Williams spoke English with an accent typical of other Mohawks who had learned English as children. See Ellis, “Recollections,” 323.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Hanson, Lost Prince, 383.

[26] “A Bourbon Really Among Us!” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, 24 September 1853.

[27] “The Iroquois Bourbon,” Southern Quarterly Review, July 1853.

[28] “Rev. Eleazer Williams, Christian Enquirer, 12 February 1853. In reality, Williams was only three years too young to be the Dauphin. “Summary,” National Era, 19 May 1853.

[29] Review of Hanson’s Lost Prince, in Putnam’s, February 1854.

[30] “Eleazer Williams,” Christian Inquirer, 26 February 1853.

[31] Hanson, The Lost Prince, 395-397.

[32] Ibid., 397.

[33] Eleazer Williams to “Rev and Dear Sir,” 17 April 1853,” EWP, Reel 2, Frame 625. On the Buffalo Creek debacle, see Laurence M. Hauptman, Conspiracy of Interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999).

[34] Eleazer Williams to Rev. William Berrian, 28 February 1849; Elijah Skenandoah, Cornelius Stevens, Neddy Atisquette, Adam Swamp, Thomas King, Henry Powlis, Daniel Williams, Jacob Cornelius and Daniel Bread to Bishop Jackson Kemper, 1 June 1849, both in the Eleazer Williams file, Archives of Episcopal Diocese of New York, New York City (hereafter AEDNY).

[35] H. G. Woutman to Benjamin Haight, 29 October 1849, AEDNY; Woutman to Standing Committee, Protestant Episcopal Church, 25 December 1849, AEDNY; Henry Addison (at the order of Eleazer Williams) to Dr. Haight, 5 July 1850, AEDNY; Eleazer Williams to the Standing Committee, 5 December 1851, AEDNY.

[36] Jackson Kemper to Eleazer Williams, 5 May 1849, AEDNY; Kemper to Dr. William Berrian, 5 May 1849, AEDNY; Kemper to Berrian, 19 June 1849, AEDNY.

[37] H. G. Woutman to Standing Committee in New York, 25 December 1849, AEDNY; Eleazer Williams to the Standing Committee, 5 December 1851, AEDNY.

[38] Cincinnati Weekly Patriot, 21 May 1853, Clipping in EWP; Eleazer Williams to William Berrian, 29 June 1850, AEDNY; Letter to Rev. Dr. Haight from [illeg], 29 November 1851, AEDNY; Eleazer Williams to Haight, 14 April 1851, AEDNY.

[39] Eleazer Williams to Rev. John McVicker, 25 November 1851, AEDNY; John G. Newton to Standing Committee, 16 December 1851, AEDNY.

[40] Eleazer Williams to Dr. Haight, 5 July 1850, AEDNY.

[41] Jackson Kemper to Dr. Haight, 23 August 1851, AEDNY

[42] These financial difficulties date back to at least 1840. See the leases Williams signed in the summer of 1841 to lands in Wisconsin (perhaps to support his wife and child there) to Joseph Allen and Augustine Lavine, EWP, Reel 2, frame 0161; Eleazer Williams to Bishop Onderdonk, 12 July 1841, EWP Reel 2, Frame 0548; Lien filed against Williams by John Last, EWP, Reel 2, Frame 0170 and Eleazer Williams to William J. Eustis, 3 January 1844, EWP, Reel 2, frame 0562.

[43] Ellis quoted in Syracuse Daily Star, 17 March 1853, clipping in EWP Reel 7.

[44] Eleazer Williams to Mary Hobart Williams, April 1854, EWP, Reel 2, Frame 630; Eleazer Williams to Madam R. V. Hotckiss, EWP, Reel 2, Frame 619; New York Church Journal, 29 September 1853.

[45] Eleazer Williams to Reverend Jackson Kemper, 29 September 1853, EWP, Reel 2, frame 635.

[46] Eleazer Williams, Letter dated 4 august 1852, in undated and unidentified newspaper clipping, EWP, Reel 7.

[47] Troy (NY) Daily Traveler, 23 July 1855.

[48] Ibid. Williams gave a similar address, at an earlier point in his career, as an Indian, in that he described the efforts of “the man from the East . . . to extirpate us from the face of the Earth.” (Emphasis Added). See EWP, Reel 7, frames 2-3.

[49] Clipping from The Banner of the Cross, 1 April 1854, EWP, Reel 7.

[50] Sentinel and Witness, (Middletown, CT), 9 January 1855, in EWP, Reel 7.

[51] Washington, D.C. Daily National Era, 2 March 1854, Clipping in EWP, Reel 7.

[52] Charles Caldwell, Thoughts on the Original Unity of the Human Race, 2nd ed., (Cincinnati: J. A. and U.P James, 1852), 80-81; Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 117-118; Bruce Dain, A Hideous Monster of the Mind: American Race Theory in the Early Republic, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), vii.

[53] Dain, Hideous, 197-198; Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny, 127; Robert E. Bieder, Science Encounters the Indian, 1820-1880: The Early Years of American Ethnology, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 19??), 70-75.

[54] Samuel George Morton, Crania Americana; Or, a Comparative View of the Skulls of Various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America, (Philadelphia: J. Dobson, 1839), 5, 67.

[55] Ibid., 74, 191.

[56] “The Eleazer Williams Humbug,” New York Herald, Undated Clipping, EWP, Reel 7, frame 0181.

[57] Syracuse Daily Star, 17 March 1853; A. G. Ellis to Lyman Draper, 19 January 1880, EWP Reel 7, frame 0054.

[58] C. C. Trowbridge to Lyman Draper, 24 September 1872, EWP, Reel 7, Frame 0047.

[59] “Have We A Bourbon Among Us?” The Daily Dispatch, 29 August 1854.

[60] Hanson, Lost Prince, 395.

[61] Undated clipping, EWP, Reel 7.

[62] “The Bourbon Question,” Clipping from 1853, in EWP, Reel 7; Troy (NY) Daily Traveler, 23 July 1855, EWP, Reel 7.

[63] Hanson, Lost Prince, 393.

[64] J. K. Bloomfield, The Oneidas, (New York: Alden Brothers, 1907), 210.

[65] Newspaper Clippings, EWP, Reel 7.

[66] Clipping from the Literary Repository of the Camden Young Ladies’ Institute, (Camden, N.J.), 1 May 1854, EWP Reel 7.

[67] Eleazer Williams to Edward Henry, 4 December 1856, EWP, Reel 2, Frames 231-233; New York Times, April 15, 1858.

[68] John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America, (New York: Vintage, 1995), 246.