You have heard it before. I am not sure how long political leaders have been doing it, but it has increasingly come to bother me. A representative in Congress, asked about this or another issue, will make reference to “the American Taxpayer,” as in, “we can’t waste the taxpayers’ money,” or the “American taxpayers did not send us to Congress” for whatever thing it is that representative opposed.

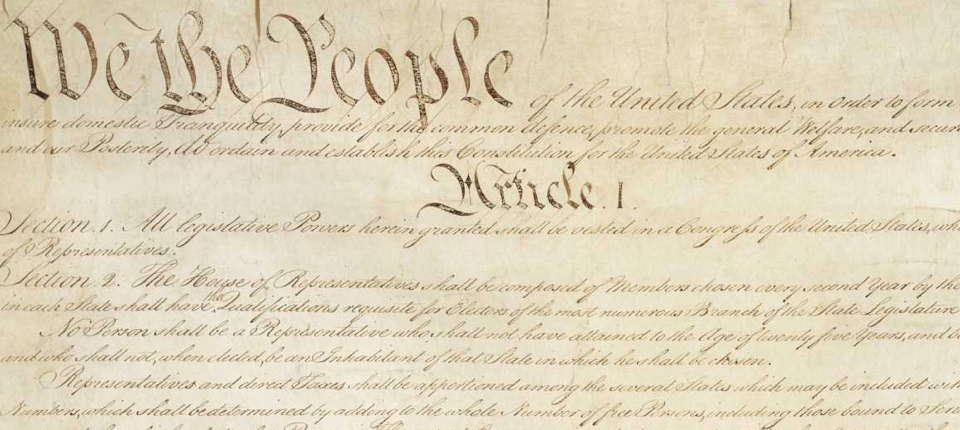

I find myself bringing this up in my classes. I am teaching my department’s course on the American Revolution right now, and of course, taxation played a huge role in the breakdown of the imperial relationship between Great Britain and its American colonies. Those English subjects in America conceived of taxation as an act of the people, which is why they believed that tax bills could only originate among their chosen representatives. The entire body politic could not gather in one place, so they chose representatives to voice and protect their interests. Only those chosen representatives could bestow the people’s property upon the government. Any appropriation of the people’s property without the consent of their chosen representatives was, in essence, theft.

The revolutionary generation believed that the purpose of government was to pursue the good of the whole, a concept they identified with the word “Commonwealth.” In order to secure the common wealth, citizens needed to exercise virtue, which meant the capacity to sacrifice one’s own private interest for the good of the whole. In order to act in a manner that was virtuous, citizens needed to be independent, subject to the control of no one else. Citizens also needed to be active, alert, and informed, for the founding generation believed that a supine and ignorant citizenry made fit tools for tyrants.

That was a much more robust conception of citizenship than so many of our political leaders embrace today. We are, in the view of too many of them, mere taxpayers. We pay our money to the government and, in their view, we ought to expect something in return. It is a transactional relationship. More than we let on, a large number of political leaders run government like a business, in that they view us as customers. Too few of us complain about that.

Because this is an interpretation that I suspect would horrify not only the founders but many writers on politics, government, and justice over several thousand years in the western tradition. In our constitutional system, we are the government. We formed a more perfect union, and as sovereign people, placed power in the hands of state and federal governments. Speaking of Americans as “taxpayers” diminishes the importance of courageous and informed citizenship, something that is obviously in too short supply these days.

Citizenship is not always easy. It is not supposed to be. Plato expected the men most suited to lead to be reviled by the people. Cicero warned that government service came with insults and the possibility of injury. But, still, the obligation to serve remained. “Both alone and with many, we will unceasingly seek to quicken the sense of public duty.” Thus reads the Oath of the Athenian City State, etched into the walls of Maxwell Hall at Syracuse University, where I went to Graduate School. Citizens must carry the obligation to “transmit this city not only less, but greater, better, and more beautiful than it was transmitted to us.” Considerably more is asked of us than merely paying taxes. The city, its government, are ours. Our political leaders are happier when we are passive, when we do not question them, when we do not hold them to account. They want us to pay our bills and be quiet. Maybe it has always been that way. Our leaders, for instance, seldom make themselves available to the press or people. They seldom appear in venues where they can be asked an unfriendly or critical question. The leading networks no longer investigate, because it is cheaper and easier to bring on pundits to debate each other. They seldom have the opportunity to hold our leaders to account and when they do they all too often fumble.

So, Citizens, it is on us. We have to engage. We have to stay informed and active because we are the government. We need to engage actively, critically, energetically, in pursuit of the common good. Doing so requires information and courage. Those who participate in public life, or who speak truth to power, will be shouted at and reviled. They will take their lumps. But doing so is the obligation of a citizen.

Now, perhaps, more than ever. Corporate power in our political system increases every day. Campaigns and candidates are awash in dark money. Those who challenge the President are shouted down, as he engages in grift and graft to a degree unprecedented in American history. Sixty-two million Americans voted for a petty and small-minded bigot to become arguably the most powerful person on earth, and if we do not do our job, he may well be reelected.

We are not mere taxpayers. We are, and must be, citizens. We must engage in the pursuit of the common good. We are not consumers of government services. WE ARE THE GOVERNMENT. We must let our leaders know, through petition, appeal and, if necessary, protest, that it was “the people” who as sovereigns bestowed the powers they exercise on our behalf. If we fail, that common good will become ever more elusive.

During the Vietnam War protests a popular slogan was “Suppose They Gave a War and Nobody Came” based on a 1966 magazine article, and later turned into a B-rated comic movie. In reality, the anti-war movement was dead serious in their desire for the people to rise up against the political “establishment.” Then came the call “Hell No, We Won’t Go.”

This was a generation trying to prove that the people are the government. They were trying to engage in participatory government and they did effect changes in some institutions, notably academia, civil rights, and the culture of the 1950’s.

So you challenge people to stay informed and to stay active because we are the government. Supposedly an informed citizenry will bring about change if they become active and participate in government. But what does that mean? Remember what Tip O’Neil said, all politics are local. How many people who complain about politics at all levels are willing to actually participate, even at the local level. Local political committees nominate not only local (i.e. town or city) candidates, but also state and federal representatives. It’s a very dirty process but only when citizens are willing to devote a minimal amount of time to participate and raise their voices against entrenched corrupt local candidates (i.e. Bill Moehle in Brighton, Joe Morelle in the NY-25 CD) can we expect to effect change higher up the ladder.