On July 7, 1967, Chief John Big Tree died on the Onondaga Reservation. Born Isaac Johnny John, perhaps in 1877 in Michigan, the Seneca actor appeared in nearly five dozen movies between 1915 and 1950. He played a scout in “Stagecoach” along side a young John Wayne in 1939, and with Henry Fonda in “Drums Along the Mohawk,” and, again with John Wayne, in “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon.” That was 1949, his second-to-last film. He played Chief Pony That Walks.

After his retirement from the movies, Big Tree settled at Onondaga, where he stayed near the center of the community’s life. According to a story about the upcoming Green Corn Dance hosted by the nation in 1951, an event that was open to the public and well-promoted in the Syracuse newspapers, the Post-Standard noted that “Chief Bigtree, motion picture actor, and is wife, Cynthia, will appear” along with Mrs. Bigtree’s “famous green corn soup and ghost bread.” Two years later, along with Percy Smoke, Nelson Schenendoah, Jimmy Noland, and others, Big Tree joined with Onondagas at the Syracuse Boys’ Club’s Camp Zerbe to “relate Indian lore and demonstrate tribal dances.”

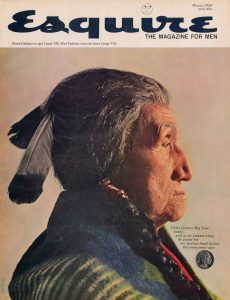

In 1964, Big Tree appeared on the cover of Esquire magazine in a pose that looked back to what he seemed to consider his most famous role. Big Tree claimed that James Earle Fraser used him as one of his models when he sculpted the image for the “Indian Head” or “Buffalo” nickel, which circulated from 1913 to 1938. Big Tree claimed as well to have posed for Fraser’s most famous sculpture, “The End of the Trail.”

Fraser denied this. In a letter he wrote to Calvin Coolidge’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the summer of 1931, he wrote that “the Indian head on the Buffalo Nickel is not a direct portrait of any particular Indian, but was made from several portrait busts.” It was, in a sense, a composite image. Fraser wrote that he “used three different Indian heads.” The name of one of them, perhaps Big Tree, he said he could not remember. The other two included “Irontail, the best Indian head I can remember; the other was Two Moons.” Some thought that the third Indian was not Big Tree but Two Guns Whitecalf, but Fr aser was certain this was not the case. Fraser was not always precise in his recollection.

aser was certain this was not the case. Fraser was not always precise in his recollection.

Nonetheless, John Big Tree made many appearances as the “Indian on the nickel,” and when he died in 1967 the reports identified him as the model for Fraser’s image. Big Tree, the wire-service story in the Syracuse Post Standard noted, was best “known for his acting and for his likeness on the Indian head nickel.”

As I’ve indicated in previous posts, my research right not consists of reading lots of newspaper articles about the Onondagas. I have quite literally thousands still to read through. John Big Tree, obviously, is a very tiny part of the much larger story I intend to tell. At a period when Onondagas appeared at the Indian Village at the New York State Fair in Plains Indian dress, an effort to assert their identity as native peoples as they fought state efforts to tax their lands, as they contended with polluters on the reservation, and began to assert that wampum belts and other items housed in the New York State Museum were part of their cultural patrimony, John Big Tree was a former celebrity whose presence appealed to his audience’s nostalgia. That’s revealing. White people in the state carried powerful assumptions about who native peoples were and who they ought to be. More than anything, they tended to view native peoples, and their culture and their language and their ways of living, as part of the past. If any number of white people had their way and any number of points in their history, I tell my students, the Onondagas would have been gone. In a sense, they had to appear in a certain manner–that of the Plains Indian–in order for white people to see them, to consider them authentic. At the time John Big Tree died in 1967, that was beginning to change. And the magnitude of that change will be most visible when we get to our next film next week.

I find this “Onondaga’s and the Movies” series very interesting. I’m curious to see how far you will be able to following this path, but it emphasizes the message you’ve been making in other essays.

Thanks for reading, Kurt. I hope to have a piece on the early 1990s version of “Last of the Mohicans” up in a couple of days. Stay tuned.

The other day I caught John Big Tree in the 1941 movie “Western Union.” He plays an Oglala chief and carries on several conversations with Randolph Scott. While most of the other actors playing Indians, like “Iron Eyes” Cody, were white and spoke gibberish, it sounds like Big Tree was speaking his lines in Seneca[?]. Even Randolph Scott’s lines echoed many of the words that Big Tree was saying.

Michael,

From my research, I show he was born on or near the Cattaraugus Reservation in NY. The U.S. Indian Census Rolls has his birth year at 1877. Feel free to contact me.