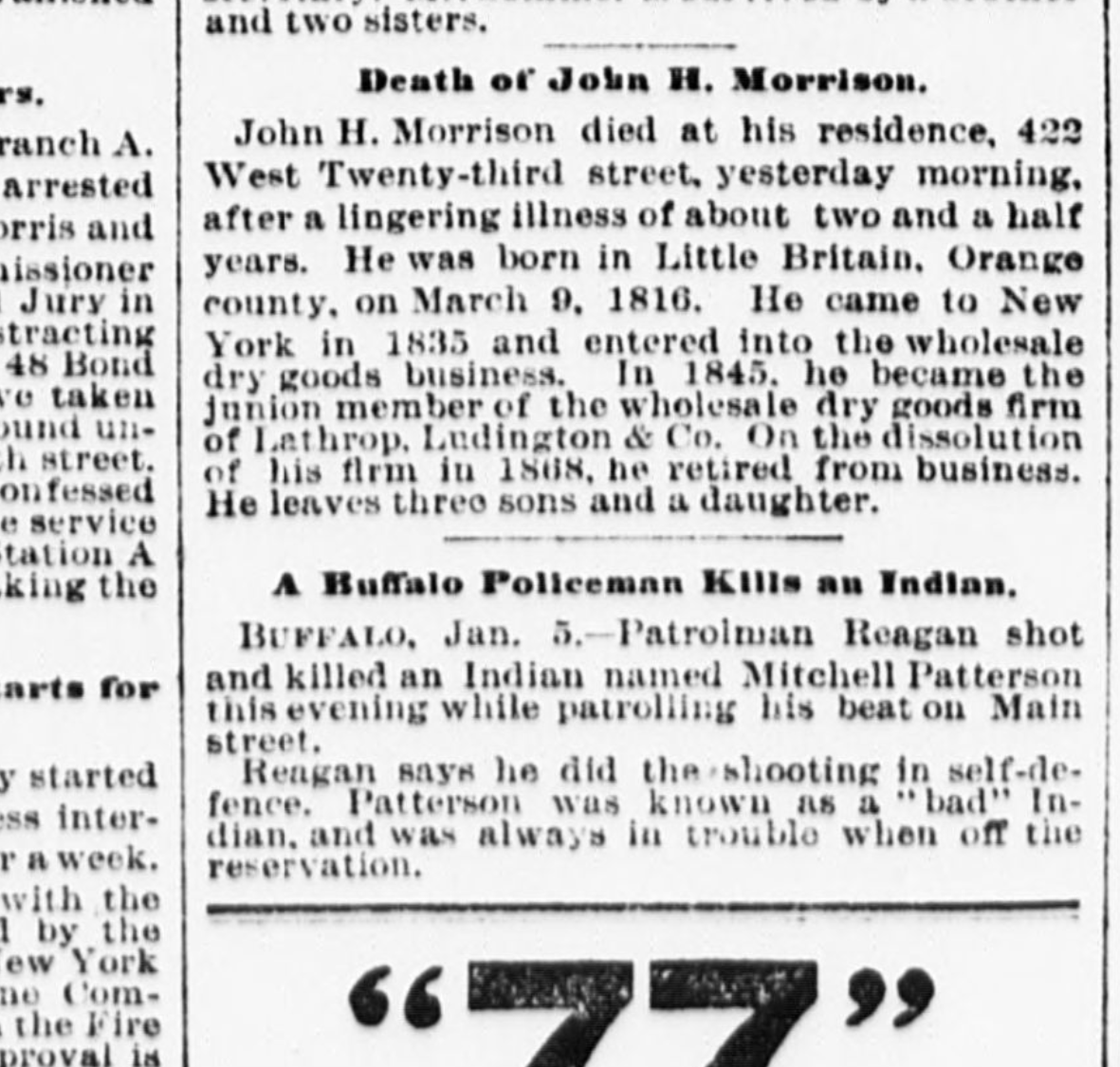

He’s a “Good Injun Now.” That’s how a headline in the Buffalo Morning News announced the death of Mitchell Patterson, a Tuscarora Indian whose life of violent crime came to a close on Lock Street in Buffalo in January of 1895.

That headline writer was riffing on the famous line attributed to the American military leader Philip Sheridan, perhaps the most famous thing Sheridan ever said: “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” It was a joke that headline writers liked.

I have put a lot of time recently into my current research project, a history of the Onondaga Nation. I am at that stage of the research when I am collecting and reading newspaper articles. Variations on this theme appear quite often. Two decades after Patterson’s death, the Brooklyn Citizen published a story under the headline, “A Good Indian–And Alive,” chronicling the surprising career of Charles Doxon, an Onondaga who attended the Hampton Institute, and became a regular lecturer for the Six Nations Temperance League and on matters religious.

Newspapers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries contain a wealth of information about the lives of native people. They provide a window into the events that impacted these communities, and through a glass darkly, into the lives of native peoples as they made their way through a world that at best wanted them to disappear. Newspapers have allowed me, for instance, to reconstruct the lives of Onondagas who attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and other Native American boarding schools: those who succeeded as farmers, or as housewives, or as leaders of a native nation. We meet football players and musicians in the newspapers, but also Onondaga bootleggers and outlaws, including a man who took his own life after shooting a Madison County sheriff’s deputy.

They are rich sources, and indispensable. I could not do the work I need to do without them. I subscribe to newspapers.com, use a couple of the newspaper databases to which my college library provides access, and I make frequent use of the quirky Fulton History website, which contains a trove of information.

They are flawed sources, too. They include an enormous amount of racist and stereotyped information about native peoples. They report on examples of what their editors still considered savagery, and they told stories of crime and dysfunction in native communities. Besides stories chronicling the resistance of native peoples to the forces of settler colonialism, they carry stories of Onondagas shooting their guns at the moon during an eclipse, and resting satisfied that their actions returned the world to light, of “Pagan” ceremonies, and of superstitious dancing and despair. Much that took place in these communities, I am certain, struck editors as entirely uninteresting and unworthy of even a single column inch. Much, I am certain, has been missed or left out.

Still, I had to check. And reading newspapers can lead one down a rabbit hole, as you follow a lead you did not expect through its challenging twists and turns. It was on one of these journeys that I encountered Mitchell Patterson.

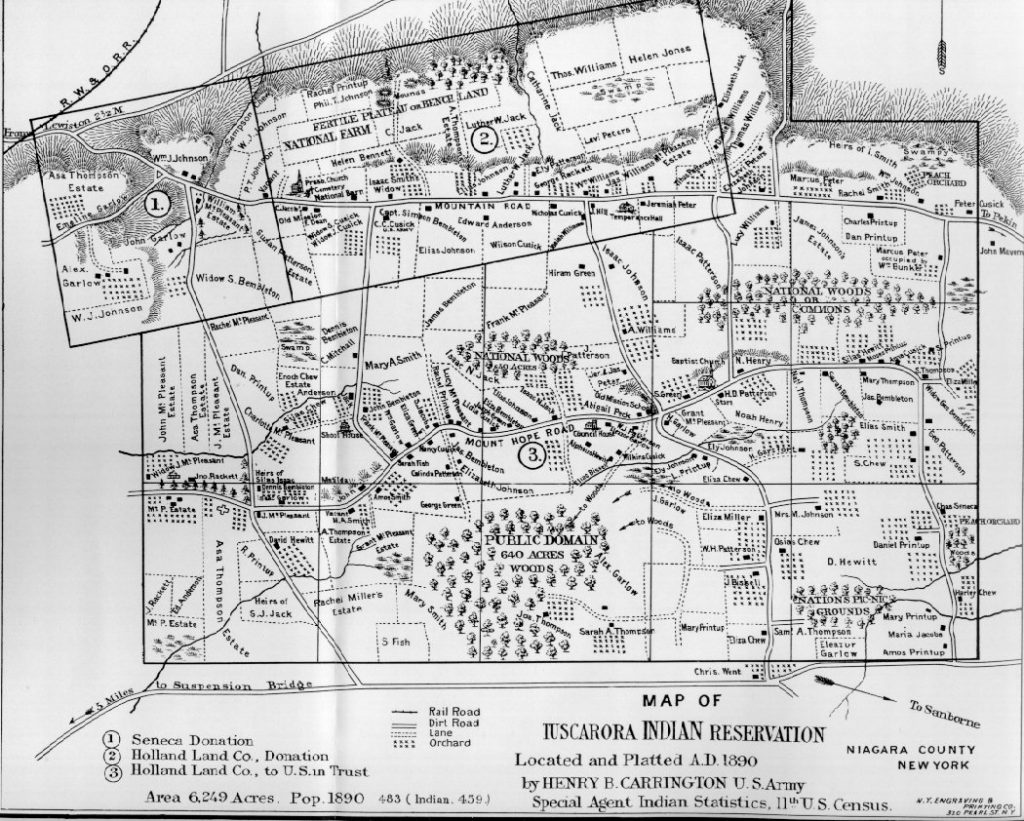

In June of 1880, Patterson attacked “a young white woman” in Lewiston, Niagara County, not far from the Tuscarora Reservation in western New York. He “cut her eyes out, split her ears, and otherwise disfigured her.” Other accounts disagreed about the identity of the victim, indicating that Patterson’s wrath fell upon his aunt Nancy, who told him that he could not come home drunk any more. Patterson got angry, one Tuscarora neighbor recalled, and, in the Indian-speak newspapers loved to utilize, “he go sharpen stick and stab her eyes out.” Patterson fled across the Niagara River into Canada. Officials found him in a Brantford jail, not far from the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario, due to be released in October on some unrelated charge. He was somehow arrested in New York, and sentenced to ten years in prison for the violent attack.

He must have been released early. Patterson shows up in the papers again in April 1889. The Niagara County grand jury indicted Patterson for “shooting at an officer on the Tuscarora Reservation” the previous February. Four years later the district attorney in Lewiston charged him with shooting “Zacharia Green on the reservation.” And just seven months after that, a Niagara County court found Patterson guilty of selling alcohol to Indians on the reservation. He was imprisoned in the county jail for two months and fined twenty-five dollars.

He did his time. The Buffalo Commercial reported on March 28, 1894, that “the sentence of Mitchell Patterson, the bad man from the Tuscarora reservation, expired to-day, and a warrant was waiting for him the moment he was released.” The Commercial pointed out that Patterson “is a bad man and Indian that has made the marshal no end of trouble, and when he gets in this time it is to be hoped he will stay.” The charge, this time, was the beating of Lafayette Printup, in Sanborn, the previous November, 1893.

Patterson disappeared from the papers for a few months. He appeared again in November of 1894. Perhaps he had been in jail, but it is not possible to tell from the newspapers. Wherever he had been, that fall day Patterson went to the home of his neighbor, a “good Indian” named Isaac Clause. Patterson called for Clause to come out, and as soon as his neighbor appeared, “Patterson knocked him down and kicked him in the head.” Then he forced Clause to come with him, and “marched him to the village store and made him treat to tobacco, afterward robbing him of all his money.” Patterson “pounded and robbed” Clause, said one paper, “leaving him in a semi-conscious state in the road.” Clause’s relatives feared that he “is so badly injured he may die.”

Just two months later, Buffalo police officer Daniel Reagan began to hear about an Indian walking along Commercial Street in the city who had made a number of “indecent remarks” to a couple who was out for the evening. Officer Reagan found the suspect–it was Patterson–and he began to follow. Patterson turned on to Evans Street and picked up his pace. Reagan caught up, grabbed the much larger Patterson by the collar with one hand, and pulled his night stick out with the other. Patterson yelled, “Let go me, you son of a gun!” He then pulled out a pistol, pointed it at Reagan’s head, and then turned and ran without firing a shot.

Officer Reagan pursued. Patterson ran in the middle of the street, Reagan on the sidewalk. An “iron framework” ran between them, that “separated the drive way on the bridge from the footway for pedestrians.” At one point, Patterson turned and fired a round. He missed. Reagan drew his own weapon and continued to pursue.

A couple of seconds later, Patterson turned onto Lock Street, “a narrow, unlighted thoroughfare.” Reagan “could see the tall form of the Indian running along the west sidewalk of Lock Street,” about fifty feet ahead. Patterson fired again, and this time Reagan returned fire. “There came a fusilade of shots, which were heard from blocks around.”

Reagan hit Patterson three times. He and some witnesses carried the wounded man into the light of a saloon. They called for an ambulance, which rushed Patterson to the hospital. The surgeons, the newspaper reported, “have little hope of the man’s recovery, as a great hemorrhage resulted from the perforation of the liver, and the shock to the system was intense.”

And, then, the only description of Patterson. Six feet, two inches tall, weighing close to 250 pounds. He was “about 40 years old,” and “has the face of the typical reservation Indian,” with “a sparse mustache and goatee.” Patterson was “profusely tattooed.”

On his right arm is a figure of Mitchell, the pugilist, and on his left the word ‘Wisdom,’ in large letters. On the left leg is another potrait of Mitchell, for whom his namesake seems to have a great admiration.

In the hospital, Patterson gave an “ante-mortem statement” to the coroner.

My name is Mitchell Patterson. I live on the Tonawanda Reservation. I was walking on Canal Street and a policeman shot me. Another Indian was with me by the name of Frank Wooley, who had a gun and shot at the policeman. I had no gun. The other Indian had a gun. I sail on the lakes and come to Buffalo quite often. He had two guns and he gave one to me I shot once but did not hit anybody.

This was certainly a confused, and confusing account, that does not square at all with what Officer Reagan reported. Evidently the coroner did not find it satisfactory, either, because he visited the hospital again the next morning to take an additional statement from Patterson, who must have been in miserable shape. I include it here in its entirety:

My name is Mitchell Patterson. I live on the Tuscarora Reservation, near Lewistown. I am thirty-five years of age and am a single man. I came to Buffalo from Keating Summit, where I was working in the lumber regions, about a week ago. I have been boarding with a man named Walters, on Main Street. I was walking on Canal Street about 8 o’clcok last night when a policeman came up to me and said: ‘You big Injun; want you.’ He put his hand on my collar. I jerked away and ran over the Evans Street bridge, and there, I think, I shot at the policeman once. I ran into Lock Street and shot at him again, and he shot at me and hit me.

I carried a revolver one week, which I bought on Canal Street. I had two extra cartridges in my pocket. I do not remember if the policeman told me not to shoot or not. I was drunk and do not remember everything. I might have shot four or five times. I do not remember. I served three years in Auburn [a state penitentiary] for fighting another Indian. I was sentenced at Lockport. I kicked the life out of him. I have been out of prison for two or three years.

A more detailed account, indeed, but one that contradicts much that appeared in the first statement, taken the night of the shooting. The coroner thought the second statement was more accurate and thorough, but still not complete. Patterson was dying of his wounds, answering questions after surgery. I can hear in his narrative, I think, the coroner’s questions, Patterson’s short answers, and the coroner’s efforts to fashion this into a narrative.

Patterson died at 3:00pm, roughly eighteen hours after Officer Reagan shot him. In the days that followed his death, Buffalo newspapers continued to flesh out Patterson’s story, reporting on the bits of information they recovered from Tuscaroras who visited Buffalo. They told the story of a “heap bad Injun,” to be sure, who seemed to have terrified his native neighbors in several native communities, as well as the police who always approached him armed because they knew Patterson was ready for a fight. Violence defined Patterson, according to the newspaper reports.

Patterson was a life-long criminal with a violent temper, and he spent more than half his adult life behind bars. But these stories, perhaps in ways the editors did not intend, paint a more complex picture of a Native American man who traveled through Haudenosaunee communities across a broader Iroquoia. He spent time at Onondaga, at Tonawanda, and at the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario. He worked on Great Lakes Steamers, cut timber in Ontario, Michigan, and New York, and squeezed a few bucks here and there by selling alcohol to his neighbors at home on the Tuscarora Reservation.

He had family connections. He beat Noah Patterson, his grandfather, to defend his grandmother from a wife beater. After the latest attack from her husband, she “got mad and look for a man big ’nuff to lick Noah.” Mitchell Patterson fit the bill. Three Tuscaroras visited Mitchell Patterson in the hospital, according to one story more to satisfy their curiosity than express their sympathy. They said little, according to a white witness, but that does not mean they did not care. Mitchell Patterson’s mother–she is unnamed in the newspapers, and identified only as “Old Mrs. Patterson”–arrived at the coroner’s office two days after her son’s death. The newspaper said “there was not a trace of grief upon her face.” She wanted to see her son’s body, and carry it home for burial. The coroner guided her in. “She viewed the body for a few moments,” the newspaper said, and “uttered a few words in the dialect of her tribe.” Her wagon was not large enough to carry the remains, so “it was accordingly arranged to place the body in a rough box and ship it to Sanborn for burial in the Indian cemetery there on the Tuscarora Reservation.”

Perhaps “Old Mrs. Patterson” showed no grief. But I am not sure that is true. One of the many stereotypes about native peoples was their supposed “stolid” nature. Maybe the coroner saw what he wanted to see. Perhaps the grief she felt was real, significant, and deep, expressed in a few quiet words in the Tuscarora language, by a mother who wanted to take her wayward son home for burial.

Newspapers provide a remarkable and important source for reconstructing Native American life. But we must remember that white newspaper editors and non-Indian journalists made decisions about their paper’s content, and they did not often ask native peoples what they thought. Indians appear in the newspapers when the white people in charge wanted them to appear, when they did something that they felt might interest their white readers. This might include instances of the continuing “savagery” and “paganism” of Haudenosaunee peoples. Native peoples appear frequently in the newspapers as athletes and criminals, too. Boarding school students who did good, and boarding school students who met tragic ends, appear in the papers. There are also stories of Native American organization and institution building, protest, and activism: instances when native peoples worked together to protect their communities in ways that non-natives might perceive as threats to their own lives, liberty, and property.

In between, in the gaps, silences, and the behaviors and actions described by newspapermen but not understood, there are fleeting images of a world that historians of Native Americans struggle to recover. Mitchell Patterson may have been a criminal, a sadist, a “Bad Injun,” and a source of terror to those who knew him. But he also moved through indigenous communities throughout western New York and Ontario, communities with stories that have not always been told with the richness they deserve and a careful and critical analysis of the sources will allow.