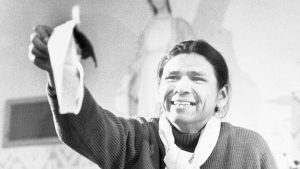

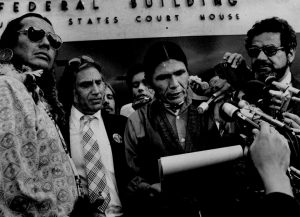

Dennis Banks, one of the most important leaders of the American Indian Movement, or AIM, died last week. Banks was eighty years old.

The obituary that appeared in the New York Times, written by Robert McFadden, covered the key points in Banks’ long career, but it has justly been maligned for its resort to stereotype in describing Banks’ appearance (“high cheekbones,” “raven-haired,” “dark, piercing eyes”); its over-emphasis on Banks’ considerable legal troubles without describing the harassment and persecution AIM faced from federal, state, local, and, at times, tribal police officials; and a nasty, judgmental tone when it came to Banks’ family life and large number of children.

If you follow the conversation on Twitter about the Times obituary, you will see that some of these critiques are sensible, others a bit off-base. Many of the critics suggested that the obituary dishonored Banks by pointing out his criminal troubles and the confrontational and sometimes violent nature of AIM activism.

My own objection to the obituary is a bit different, for it seems to me that McFadden badly misunderstood the goals and the significance of the American Indian Movement and Banks’ role in it.

We should be clear. AIM has, to too great an extent, monopolized discussions of American Indian activism in the second half of the twentieth century. This is a failing of the historians, and not AIM itself. Native American “activism,” a term that has been used uncritically, at the local and reservation level, and often occurring away from the gaze of national media, long predated AIM. Still, McFadden questioned the significance of AIM’s activism and, in so doing, much of Banks’ life work. Banks, he said, brought some attention to Indian causes, but he “achieved few real improvements in the daily lives of millions of Native Americans living on reservations and in major cities” and who continue to “lag behind most fellow citizens in jobs, housing, and education.” He never slayed the dragon.

I am not quite sure what McFadden expected, and what he might have defined as meaningful change or “real improvements.” His language, which I am willing to believe was unintentional, still struck me as a snide dismissal of AIM and of American reform in general. If problems still exist after the reformers’ careers have ended, McFadden seems to suggest that it was all for naught.

Of course AIM made outrageous demands that never were going to be fulfilled. Of course their actions, at time, generated opposition among certain members of the communities in which they worked. At times, by any standard, AIM members behaved badly. It would be foolish to expect native peoples to speak with one voice, for factionalism and disagreement are facts of Native American life. And it would be foolish as well to expect one organization, no matter how charismatic its leaders, to wipe out the enormous injustices and inequalities native peoples faced.

Banks plays a significant role in my present book project, a history of the Onondaga Nation. After jumping bail in South Dakota, Banks found shelter in California. Jerry Brown, the state’s once and future Democratic governor, refused to honor demands that he be extradited. But when the Republican George Deukmejian became governor of the Golden State, Banks made his way to New York, where he found “sanctuary” on the the lands of the Onondaga Nation. He stayed there for much of 1983 and 1984. The decision of the chiefs and clanmothers at Onondaga to grant Banks sanctuary was part of the Onondagas’ assertion of nationhood that made it, in many ways, the center of discussions about Native American Nationhood in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Banks missed out on a lot during his sanctuary, was homesick, and at times struggled to keep busy on the small nation territory. He organized running clubs, took a job, but the evidence in Syracuse newspapers and other sources suggest that not all Onondagas were happy with his residence on the nation territory. I have much left to learn about Banks’ time on the Onondaga Nation, but it seems that all these things factored into his decision to leave. He surrendered to authorities in the fall of 1984.

McFadden, in an obituary rife with cliches that focused on dysfunction, violence, and alcoholism in Native American communities, could not see the significance of AIM’s work. He did not understand the toll persecution and legal harassment took on the movement, nor the barriers against which it operated. Nor did he acknowledge how the activism of the 1960s and 1970s, from the Fish-Ins and Alcatraz, to the Trail of Broken Treaties and the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters in Washington, to the stand-off at Wounded Knee in 1973, and hundreds of other acts of defiance and protest in Native American communities small and large, made American policy makers who previously had hoped to “terminate” Native Americans reconsider their positions. You can see the shifts in policy beginning under President Johnson, accelerating under Richard Nixon who, despite that whole Watergate thing, was a pretty good president for native peoples. And it culminated in the significant legislation of 1978, which I discuss in the final chapter of Native America, one of the most important and creative periods in law-making in all of Native American history. Of course Banks and his allies and associates left much work undone, and of course there were significant limitations in what solutions federal authorities were willing to consider, but without the efforts of thousands of native peoples, on their own, in AIM, or in other Native American rights organizations, none of this significant legislation would have been enacted.

Nobody summarized the significance of this activism better than Paul Chaat Smith, whose Everything You Know About Indians is Wrong, is a wonderful introduction to this important subject. Speaking of this period in Native American history, from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee, Smith wrote that

“It is our people at our looniest, bravest, most singular and wonderful best, and moving beyond words even to those of us who resist cheap sentiment and heroic constructions of complicated and flawed movements. Yet there it is, over and over again: Indians who objectively have little or nothing in common choosing to join people they often don’t even know who are engaged in projects as bizarre as laying claim to a dead prison on an island that is mostly rock, or picking up a gun to take sides in the Byzantine political struggles of the famously argumentative Sioux.”

McFadden said that Dennis Banks and his partner in so many AIM campaigns, the late Russell Means, were the best known Native Americans since Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Maybe so, but Americans seem to know little about Sitting Bull and almost nothing about Crazy Horse except for their names. Banks’s influence is a significant one, and all one has to do is search the archives of the New York Times to see that. It is disappointing that McFadden’s obituary is such a disappointing last word on so significant a life.