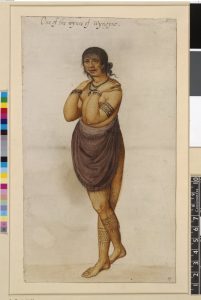

The failed governor of a failed colonial enterprise, sent packing from what would soon become the fabled “Lost Colony” of Roanoke, and a pretend aristocrat whose patron procured for him a bargain-basement coat-of-arms, John White was also an “important” and “renowned” artist whose “vivid” and “lifelike” images included an Algonquian woman he depicted with two right feet. Nearly everything John White  touched turned to shit.

touched turned to shit.

White did not lack for experience, we are told. He likely sailed aboard one of Martin Frobisher’s voyages in search of mineral wealth and a northwest passage in the 1570s. He accompanied the reconnaissance voyage Sir Walter Ralegh sent to “Virginia” in 1584 and, the next year, returned aboard the much larger expedition sent to establish a base along the coast of today’s North Carolina. He was among those men who, that summer, explored the coast to the south of Roanoke Island where he completed several paintings of the Algonquian peoples of the region and towns in which they lived, before he returned home with Sir Richard Grenville in the fall of 1585. He may have traveled more widely in the summer of 1585 to gather the information necessary to make his large map of the Outer Banks and Eastern North America. In 1587 Ralegh decided to try again, and for reasons that remain inexplicable still, he appointed White governor of what he hoped would become the “Cittie of Ralegh.” White returned home from the colony a few weeks after arriving, and would not make back until 1590. It was then that he discovered that the colony he claimed to have governed had disappeared. Five voyages to America, but he spent more time aboard ships coming and going than he actually did on American shores.

It is easy, I suppose, to view White as a pathetic figure. He brought his family to England’s paltry new world outpost. Circumstances forced him to return to England, and to struggle for several years to return to America. He never succeeded in reuniting with his daughter, her husband, and their daughter Virginia, the first English child born in America. How painful this must have been for him, to not know what had happened to his child and grandchild.

It is understandable. It must have been agonizing for White. I can imagine his pain easily. But I keep tripping over my belief, based upon reading and re-reading the surviving records, that every time John White was faced with an important choice, he made the wrong one.

Every document that sheds light on the planning for the 1587 colony, for instance, shows that Ralegh charged White with establishing his “Cittie” on the Chesapeake Bay. Relations with the Indians there the previous year offered promise. An English party spent some time there in 1585 and 1586. They found the deep water anchorage, abundant food, and peaceful Indians far more welcoming than the Algonquians in the vicinity of Roanoke, who would soon chase the colonists out of America.

Before heading to the Chesapeake, White wanted to check in on the men Richard Grenville had left at Roanoke the year before, shortly after the harried colonists evacuated. He may as well have intended to install Manteo, the Indian from Croatoan who had stuck with the colonists since 1585, as a sort of feudal “Lorde of Roanoac” to govern the region in Ralegh’s name. So they were going to check in on Grenville’s colonists, install Manteo in his new post, and then carry on northward towards the Chesapeake. Simple enough. But that did not happen, and White’s explanation why makes little sense.

White and his men clambered aboard the pinnace, a smaller ship capable of safely crossing the Outer Banks. “Simon Ferdinando,” the expedition’s pilot, told the sailors aboard to drop White’s party at Roanoke, “saying that the Summer was farre spent.” It was the 22nd of July and, White suggested, Ferdinando wanted to get on with the more lucrative business of chasing Spanish prizes.

Which makes no sense at all, for Ferdinando did not leave until the last week of August, more than a month later. White spent much of his account whining about Ferdinando, blaming him for everything and for nothing, and the charges simply do not add up. One of the ships that made up the 1587 voyage separated from the other two in some rough weather: White blamed Ferdinando for this, accusing him of trying to abandon one of the ships. At another point, Ferdinando was not certain of his latitude, and at another he thought he could find food in the Caribbean but his supplier could not be found. Understandable, perhaps, but White blamed Ferdinando for these events, too. The colonists ate poisonous fruit, manchineel apples, and to wash that down drank nasty, stagnant water, and fell ill. Ferdinado remained aboard the flagship. Still, White blamed Ferdinando, even though it was he who allowed the colonists to drink “stinking water of the pond,” and who failed to keep the colonists safe while on land. Later, the flagship nearly ran aground near Cape Fear, and again White blamed Ferdinando. And the decision to settle on Roanoke, despite instructions to go elsewhere? White blamed that on Ferdinando, too, but the only logical explanation for White and his colonists ending up on Roanoke was that he decided to settle in this somewhat familiar setting, rather than move to the Chesapeake where he had no first hand experience.

It was a bad choice. Grenville’s men were very clearly dead: White reported that his men found the skeleton of one of them. Very clearly they had been killed by Indians. Within a couple of days, those same Indians killed George Howe, one of White’s closest advisers. White attempted to carry on some diplomacy and figure out how the Indians felt about his colonists, which somehow still seemed a mystery to him. The Croatoans, always friendly, at first feared the English and lined up for battle before Manteo assuaged their fears. They lectured the English about indiscriminate attacks the year before. They begged the English not to steal their food. White decided that this was a good time to ask them for favors, and told them to carry messages to the neighboring Indian villages, indicating that the English “would willingly receive them againe, and that all unfriendly dealings past on both parts, should be utterly forgiven and forgotten.” This reflected nothing more than White’s utterly clueless understanding of the situation in which he had placed the colonists–in the midst of large numbers of Algonquians who had no interest in accepting English friendship. He was in no position to “receive” anyone.

Could White make it worse? Yes. After waiting a week, and receiving no response from the Indians, White decided to attack “the remnant of Wingina his men, which were left alive, who dwelt at Dasamonquepeuk,” across the sound from Roanoke. It was they, he believed, who had killed George Howe and wiped out Grenville’s party. White led a party across the sound, surrounded some Indians in the dark at Dasemonquepeuk, and launched his assault. As White put it himself, “we hoped to acquite their evill doing towards us, but,” he said, “we were deceived, for those Savages were our friends, and were come from Croatoan to gather the corne & fruit of that place, because they understood our enemies were fled immediatly after they had slaine George Howe.” They killed the wrong Indians. They killed friendly Indians, or at least he least hostile of the Algonquians in the region. The colony was now in dire straits, with no friends, and little provision.

Over the next several days, the English baptized Manteo, and White’s daughter gave birth to Virginia Dare. The colonists needed provisions, and White could not find any volunteers to go home to lobby for more. The colonists told White to go himself. He whined. He feared that during his absence, “his stuffe and goods might be both spoiled, & most of them pilfered away.” White refused to go. He feared that the people he led would rifle through his stuff. The next day, the 23rd of August, more of the colonists, “as well women and men,” once again told White to leave. Please. Really, just go. Don’t worry. We will be fine. We will be better off without you. They wanted him to leave. They knew who they were dealing with. They promised to sign a bond not to steal White’s crap, as if they really wanted his books and his armor. He must have found it difficult o leave his daughter and granddaughter behind, but that is not the argument he made. With a promise not to steal any of his stuff in hand, White departed for England on the 27th.

It was a hellish journey home. White survived, but many of the sailors did not. He tried again to sail for America the next year, that of the Armada, but the ship he was aboard was mauled by a French corsair. In the battle for control of the ship, White was shot in the ass, an injury that does not seem to have embarrassed him at all. By the time he finally made it back to Roanoke in 1590, he could determine only that the colonists were no longer on the island, and that the trunks containing his stuff had been dug up by Indians, broken open, and their contents ruined. So much for that bond. White seemed to know where the colonists were, though the location is not clear from his account. In any case, White was a man who nobody listened to. He could not persuade the mariners to devote the time to seek out the colonists, and White returned, once again, to England, his voyage entirely without effect.