And, like many things one looks forward to from Democratic administrations, it’s a bit of a letdown. If you are a historian who has worked with these sources, and if you have even a passing familiarity with the published scholarship on American Indian Boarding schools, you are unlikely to be surprised by anything that appears in the report’s 100-plus pages. It is a brief document, no more than an a cursory introduction into a vast, complex and important subject. But it’s a start.

Produced by Assistant Secretary–Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, the bulk of the report is an institutional overview of American Indian boarding schools and the government policies and programs that implemented, supported, and funded these institutions. The report is divided into nineteen very-brief chapters. The penultimate one includes the “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Findings and Conclusions.”

The list consists of the following:

- The Federal Indian boarding system was expansive, consisting of 408 Federal Indian boarding schools, comprised of 431 specific sites, across 37 states or then-territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii.

- Multiple generations of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children were induced or compelled by the Federal Government to experience the Federal Indian boarding school system, given their political and legal status as Indians and Native Hawaiians.

- The twin Federal policy of Indian territorial dispossession and Indian assimilation through Indian education extended beyond the Federal Indian boarding school system, including an identified 1,000+ other Federal and non-Federal institutions including Indian day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages, and stand-alone dormitories that involved education of Indian people, mainly Indian children.

- Funding for the Federal Indian boarding school system included both Federal funds through congressional appropriations and funds obtained from Tribal trust accounts for the benefit of Indians and maintained by the United States.

- The Federal Indian boarding school system deployed militarized and identity-alteration methodologies to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian people—primarily children—through education.

- The Federal Indian boarding school system predominately utilized manual labor of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children to compensate for the poor conditions of school facilities and lack of financial support from the Federal Government.

- The Federal Indian boarding school system discouraged or prevented the use of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian languages or cultural or religious practices through punishment, including corporal punishment.

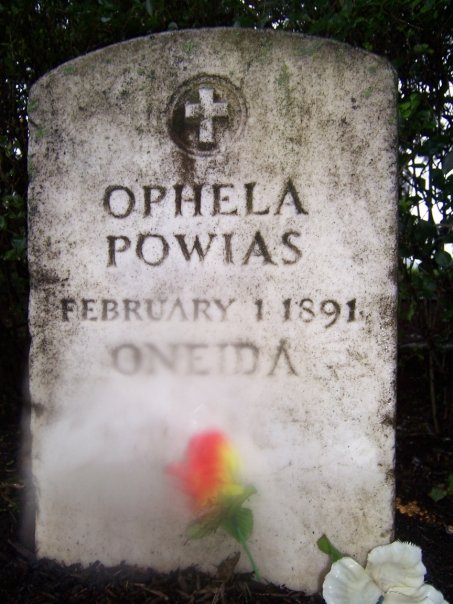

- Tribal preferences for the possible disinterment or repatriation of remains of children discovered in marked or unmarked burial sites across the Federal Indian boarding school system vary widely. Depending on the religious and cultural practices of an Indian Tribe, Alaska Native Village, or the Native Hawaiian Community, it may prefer to disinter or repatriate any remains of a child discovered across the Federal Indian boarding school system for return to the child’s home territory or to leave the child’s remains undisturbed in its current burial site. Moreover, some burial sites contain human remains or parts of remains of multiple individuals or human remains that were relocated from other burial sites, thereby preventing Tribal and individual identification.

- The Federal Government has not provided a forum or opportunity for survivors or descendants of survivors of Federal Indian boarding schools, or their families, to voluntarily detail their experiences in the Federal Indian boarding school system.

Based on that list of conclusions, Secretary Newland recommended that research continue through the “approximately 98.4 million sheets of paper” housed in boxes at the National Archives and other federal agencies. It is an enormous undertaking. The following questions, he suggested, would guide the research:

- Approximate the total number of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children that attended Federal Indian boarding schools;

- Approximate the total number of marked and unmarked burial sites associated with Federal Indian boarding schools;

- Locate marked and unmarked burial sites associated with a particular Indian boarding school facility or site, which may later be used to assist in locating unidentified remains of Indian children, Indian Prisoners of War, and Freedmen from the Five Civilized Tribes;

- Expand the summary profiles of individual Federal Indian boarding schools;

- Detail the health and mortality of Indian children who experienced the Federal Indian boarding school system, which may later be used to develop dataset(s) for analysis of health impacts of Indian boarding school attendance, including an approximate mortality rate for attendees, as the Department was responsible for the health care of American Indians and Alaska Natives until 1954;

- Identify documented methodologies and practices used in the Federal Indian boarding school system that discouraged or prevented the use of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian languages or cultural or religious practices;

- Approximate the amount of Federal support, including financial, property, livestock and animals, equipment, and personnel for the Federal Indian boarding school system, recognizing that some records are no longer available;

- Approximate the amount of Tribal or individual Indian trust funds held by the United States in trust that were used to support the Federal Indian boarding school system, including to non-Federal entities and, or individuals, recognizing that some records are no longer available;

- Identify religious institutions and organizations that have ever received Federal funding in support of the Federal Indian boarding school system;

- Identify States that may have ever received Federal funding in support of the Federal Indian boarding school system;

- Identify nonprofits, associations, academic institutions, philanthropies, and other organizations that may have received Federal funding in support of the Federal Indian boarding school system;

- Confirm additional sites within the Federal Indian boarding school system;

- Examine the connection between the use of Federal Indian boarding schools and subsequent systematic foster care and adoption programs to remove Indian children, including the Indian Adoption Project established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Child Welfare League of America, that were not repudiated by Congress until the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978

The shadow of recent discoveries of unmarked graves in Canada hangs over Newland’s report. He wants to produce a second, much larger report, that determines the locations for all unmarked and marked burial sites connected to federal boarding schools, identify the children buried in these sites, and approximates “a full accounting of Federal support for the Federal Indian boarding school system.”

In addition, Newland recommends that the government undertake efforts to identify living survivors of the boarding schools, document the students’ experiences, “support protection, preservation, reclamation, and co-management of sites across the Federal Indian boarding school system where the Federal Government has jurisdiction over a location.” Newlands wants to see a systematic effort to collect documents and house them at the Department of Interior Library “to preserve centralized Federal expertise on the Federal Indian boarding school system.” Interior should solicit help from other federal agencies which have information on boarding schools, and support non-federal entities that house information as well. Newland recommends congressional action as well: to support or strengthen NAGPRA to prevent sensitive and specific tribal information that may be uncovered as a result of the investigation; to advance legislation encouraging Indigenous language revitalization; to promote public health research on the consequences of the boarding school system; and finally to erect a federal memorial to the children who experienced the federal boarding school system.

There are some laudable goals here. Indian Boarding Schools were institutions that affected many thousands and thousands of Native American people over many generations, over many decades. The subject is vast, the documentary record so enormous as to make a complete accounting of the sort envisioned by Newland in his recommendations a mammoth, generational task. I would encourage this effort. We all should encourage this effort. This report is nothing but a start.

But I would encourage the investigators to remember that there is no more uninteresting and unimportant way to write about educational institutions than to focus on bureaucrats and leaders, policies, proposals and laws. What we need is a history of the students, with proper protections in place to guard privacy. The evidence suggests that the physical and emotional consequences of attending boarding school could be substantial and the damage could be transmitted across the generations.

This is a more difficult story to tell than to write about a “system.” It takes so much more work. It is exhausting to be exhaustive. Doing this work well, I know, can take a toll on the researchers. But we must keep in mind that the federal boarding school system was a haphazard and large network of loosely connected and poorly supervised institutions that acted with little effective federal oversight. The institutions that were part of this system began with a commitment to assimilation and erasure, to incorporating Indigenous young people into the American body politic by eliminating their Indigenous culture, language and religion. One can write a history of schools. One can write about curricula, educators, and federal policy makers. What we need, however, is a history of the Boarding schools from the bottom-up. We must never forget that this is a history that involves thousands of young people placed in an educational system that claimed as its goal cultural genocide.

I have tried to write some of these stories on this blog: I wrote about the lonely death of Carlos Pico, a Mission Indian from California. I have written about some Onondaga and Oneida Carlisle alums who traveled to Europe in 1914 as part of a circus, performing in a variant of a “Wild West” type show before the first World War broke out. Reflecting on Arlette Farge’s wonderful essay, The Allure of the Archives, I wrote about the challenge of reconstructing the lives of ordinary Onondagas who attended Carlisle and other boarding schools. And late last year I wrote a series of posts following all the Carlisle students who passed through one “outing” placement for Native American girls. The first of those posts is right here.

Schools are people. They are teachers (and for those who worked in Boarding Schools we need to learn more) and students.

I have found through my own work that descendants of boarding school students do not often know the entirety of their ancestors’ experience. I have had the opportunity to share with families the stories of their grandparents’ time at Carlisle, for instance, or lesser-studied schools like the Lincoln Institution in Philadelphia. Ten thousand students attended Carlisle, and that is only one of many schools. We need to know about the history of these institutions, but more than that, we need to recover the stories of the young people who attended them. What I am willing to bet is that the results of so enormous a historical undertaking and accounting will show that Indigenous peoples were so much more powerful, as individuals and as members of native nations, than the forces the federal government aimed at their destruction.