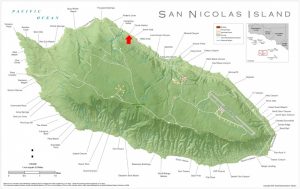

In Native America I tell the tale of the “Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island.” Thanks to some recent archaeological and historical work, we may now know more than ever before.

I grew up in Ventura, California, home of the Channel Islands National Park headquarters. Kids in my town, and I suspect around the country, learned a fictionalized version of the “Lone Woman’s” story in Scott O’Dell’s famous novel, The Island of the Blue Dolphins. In my memory, every kid had to read this book in middle school. San Nicolas is one of the Channel Islands, off of the coast of Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, though it is owned by the United States Navy, is not part of the National Park, and is not as a result as accessible as the other Channel Islands. Nevertheless, this was part of a history that was both local and significant to me, and it was a delight to have an opportunity to include the story in the textbook.

According to the conventional story, in 1853 a party of hunters led by a Californian named George Nidever encountered an elderly Nicoleño “busily employed in stripping the blubber from a piece of seal skin which she held across the knee, using in the operation a rude knife made from a piece of iron hoop stuck into a piece of rough wood for a handle.” She welcomed the white men, who could see that she lived in a camp comprised of “several huts made of whale’s ribs and covered with brush, although it was long since they had been occupied that they were open on all sides and grass was quite high within.” She had lived there for a long time, perhaps since the uprising of 1824. The white men saw that “there were several stakes with blubber on them,” and that there “was blubber also hanging on a sinew rope.” She had baskets, and “fishhooks made of bone, and needles of the same material, lines or cords of sinews for fishing and the larger rope of sinews [which] she no doubt used for snaring seals on the rocks where they came to sleep.”

At the invitation of the hunters, she accompanied the men as they hunted otter and seals on the islands. She traveled with them for several days. When the wind began to blow too strongly, “the old woman conveyed to us by signs her intention to stop the wind.” Nidever observed that “she then knelt and prayed, facing the quarter from which the wind blew, and continued to pray at intervals during the day until the gale was over.” Nidever described a Chumash woman living her life in time with a very old rhythm.

The arrival of the woman in Santa Barbara, however, made clear how much the Chumash world had changed. Less than a century after the Portolá expedition, few Californians had seen Chumash people. The old woman became a curiosity, an exhibit for the amusement of non-Indians interested in an “extinct” people. According to Nidever, “for months after, she and her things, as her dress, baskets, needle, &c. were visited by everybody in the town and for miles around outside of it.” Chumash people were exotic enough, one enterprising ship’s captain thought, that he offered Nidever $1000 for the woman. He wanted to place her on display in San Francisco, and he was willing to split the take with Nidever. Nidever refused. He learned bits of her story. She had lost a daughter, and she had grieved for many years. It was the defining event in her life. She did not have long to live. At Santa Barbara, she fell sick five weeks after her arrival and died, Nidever curiously noted, because of “eating too much fruit.” The priests at the mission church baptized her after her death and christened her Juana Maria.

Archaeologist Steve Schwartz, according to a story that appeared in the Ventura County Star on 9 October, began digging through the notes of linguist J. B. Harrington, who visited the Islands in the early 20th century, and determined that there was much more to the story. Schwartz found in Harrington’s papers answers to a number of mysteries: Why had the woman been left alone on the island in the first place? Why, after spending several decades largely alone, did she in 1853 choose to accompany Nidever? Some stories said that when the Nicloleño were leaving the island, the woman forgot her infant and left her kin to go find the child. Schwartz thought it unlikely that a woman would forget where her infant was, and that instead the child might have been 9 or 10; a nine-year old boy wandering off seemed more plausible. She remained behind with the child. According to Schwartz, “people would come to the island, see her and try to coax her to leave, and she wouldn’t leave.” Only after this child died was she willing to go to the mainland.

And though a sort of media storm took place when the Lone Woman came ashore in Santa Barbara, newspaper research indicates that bits and pieces of her story already were circulating. She appears in an 1847 Boston newspaper, and in newspapers in India, Australia, Germany and France.

Several years ago, Schwartz was part of a team that conducted excavations on San Nicolas that he believes led to the discovery of the Lone Woman’s cave. Schwartz and his colleague Sara Schwebel are assembling a Lone Woman website developed by Channel Islands National Park that will launch later this year.

The new edition of Ethnohistory includes a pair of articles that complement nicely Native America: A History. Sami Lakomaki’s “We Then Went to England: Shawnee Storytelling and the Atlantic World” critically explores native peoples’ understandings of the Atlantic World. Shawnee narratives, Lakomaki writes, “highlight the complex roles of storytelling in Native-newcomer relations and Shawnee intranational debates during a critical period when growing colonial power rapidly eroded the “middle ground” across the lower Great Lakes and political disputes factionalized the Shawnees, putting new pressures on how people constructed and forgot the past.” Also worth noting, Elsa Redmond’s “Meeting with Resistance: Early Spanish Encounters in the Americas, 1492-1524,” explores the first few decades after the beginning of the Columbian Encounter. Redmond focuses especially closely on the military components of the relationships which developed between natives and newcomers.

The new edition of Ethnohistory includes a pair of articles that complement nicely Native America: A History. Sami Lakomaki’s “We Then Went to England: Shawnee Storytelling and the Atlantic World” critically explores native peoples’ understandings of the Atlantic World. Shawnee narratives, Lakomaki writes, “highlight the complex roles of storytelling in Native-newcomer relations and Shawnee intranational debates during a critical period when growing colonial power rapidly eroded the “middle ground” across the lower Great Lakes and political disputes factionalized the Shawnees, putting new pressures on how people constructed and forgot the past.” Also worth noting, Elsa Redmond’s “Meeting with Resistance: Early Spanish Encounters in the Americas, 1492-1524,” explores the first few decades after the beginning of the Columbian Encounter. Redmond focuses especially closely on the military components of the relationships which developed between natives and newcomers.