There are histories we remember, and there are histories we forget. There are histories revealed and histories concealed. Some stories are considered important and of value. Others are dismissed as trivial or unimportant. I never knew of the Chumash Revolt of 1824. Today is the anniversary of the beginning of that rebellion. This is a story of a people’s attempt at independence.

Too many histories of Native American are, at their core, stories of white America. They are stories of settlement advancing westward, with Indians thrown in. These histories begin with Columbus, talk about the Indians who encountered the first English Colonists, and their successors who marched into the American interior. A history of Indigenous America, that frees itself from colonial timelines, that allows the history of Indigenous peoples to flow through its own channels, is a rare thing indeed.

I grew up in Ventura, California. Every chance I get I go back there. I still consider Southern California home, despite having lived in New York for most of the past thirty years. And at school, despite walking on a landscape rich with meaning for the history of Chumash peoples, it was a story we never learned. No one every mentioned the Chumash in elementary school or high school. There was talk of the missions, required in California’s social studies curriculum, and vague references to “Indians,” but nothing more than that.

One of the things I decided to do when I began work on the first edition of Native America was to write about the native communities on whose lands I have lived during my life. It was a way to avoid a narrative that simply marched westward across the continent. So I wrote about the Crows in Montana, where I taught for the first four years of my career; and the Dakota Sioux, because my family was from Minnesota; the Caddos because of my brief sojourn in the Houston area, and the Senecas because of my long residence in the Genesee Valley. And the Chumash. Because I was born. on their land along the California coast.

In the book’s opening chapters I tell students of the poorly-documented by the sixteenth century Spanish explorer Cabrillo to the region. Then the Chumash drop from the story for a while. The Chumash encountered few Europeans during the many decades after Cabrillo’s small fleet departed. A few expeditions sailed along the coast, stopping briefly, but little evidence exists as to what they did or where, precisely, they visited. They thus had little experience with European intruders, and little reason to fear the Spanish who returned in the second half of the eighteenth century. I wish I knew more about that history.

When the Spanish arrived in 1769 to secure their hold on the coast of what they called Alta California from their European rivals, José de Gálvez, the visitador of New Spain, instructed Gaspar de Portolá to undertake that task. Both Gálvez and Portolá recognized that they must treat the large numbers of native people on the coast with kindness and respect. Only with the assistance of native peoples could they control California’s verdant coastline. They lacked the soldiers and the funds for a military conquest, so Gálvez placed the “Sacred Expedition,” in the hands of a small number of soldiers and Franciscan missionaries.

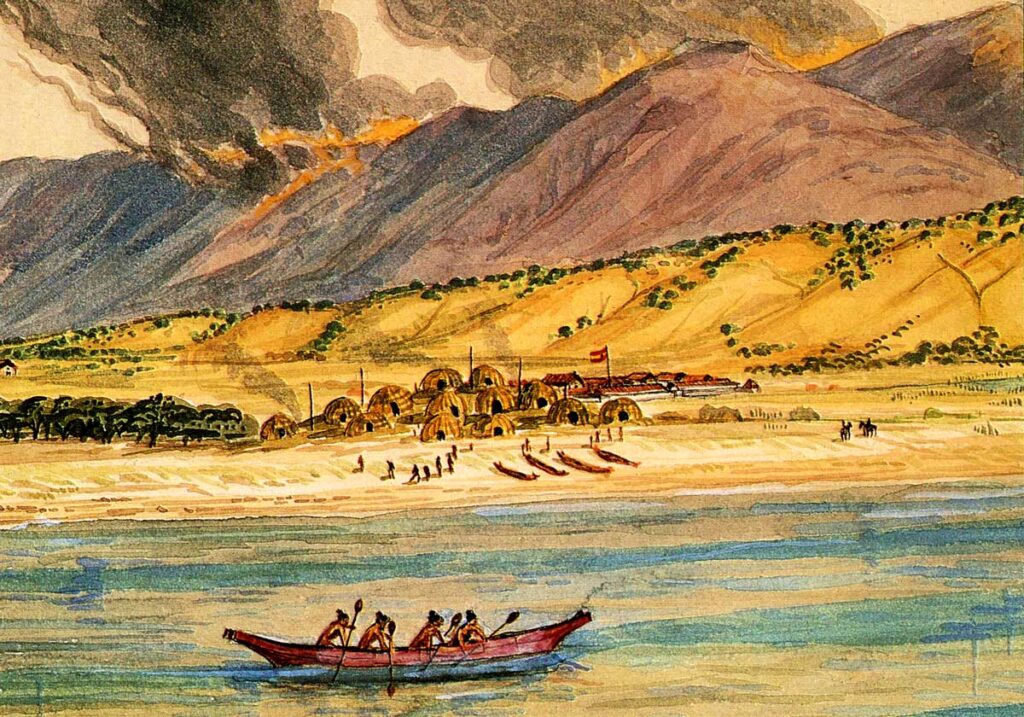

More than 300,000 native peoples, speaking perhaps as many as a hundred languages, lived within the boundaries of present‐day California. California was a paradise then. Sixty thousand lived along the coast between San Diego and San Francisco. A quarter of the plant species found in North America grow in California; more species of plant and animal can be found in California than in any other region of its size in North America. It was no surprise, then, that Portolá’s men described the Chumash as living in thriving communities. The Chumash generously traded with Portolá’s men, so much so that the Spanish leader described them as a “tractable” and “pleasant” people who felt “no fear of us.” Thousands of Chumash occupied towns and villages along the Santa Barbara Channel. They lived by the waterside, harvesting an enormous variety of readily available resources. In special storage houses they kept large stockpiles of dried sardines, anchovies, bonito, and other fish, along with seeds, nuts, and grains in adequate quantities to hold numerous feasts for Portolá’s men. Chiefs organized celebrations, designed perhaps to impress the Spanish newcomers with their wealth and power.

Portolá sought their alliance, but the Chumash looked to secure the friendship of these newcomers as well. The Spanish were impressed both by the abundance of food the Chumash collected, the variety of their economic pursuits, and the great reach of their trade networks. “Some of them,” wrote one Spanish observer, “follow fishing” while “others engage in small carpentry jobs; some make strings of beads, others grind red, white and blue clays.” The Spanish wrote that the Chumash produce “variously shaped plates from the roots of oak and alder trees, and also mortars, crocks, and plates of black stone, all of which they cut out with flint, certainly with great skill and dexterity.” They made arrows to “an infinite number,” and “the women go about their seed sowing, bringing the wood for the use of the house, and water, and other provisions.”

Despite the obvious signs of prosperity, of regional trade and a system of currency based on the manufacture of shell beads, and despite the obvious sophistication of Chumash social organization, the Franciscan missionaries who accompanied Portolá felt that the Indians would have to change. Everywhere they looked, the Catholic priests saw signs of Chumash savagery. Though the Chumash, according to one Spanish observer, lived in “communities that have fixed domiciles,” and they arranged their “well‐constructed” and “spacious and fairly comfortable” houses in organized settlements, the Franciscans hoped to relocate the Chumash to missions where they could more easily control them. Junipero Serra, the Franciscan friar who led this movement, ultimately established twenty‐one missions along the California coast, several of these among the Chumash. The Spanish constructed a presidio, or fort, at Santa Barbara in 1782, and a mission there, and at San Buenaventura, in 1786. La Purisima, near today’s Lompoc, followed one year later and Santa Ines, near Solvang, in 1808. The Santa Barbara Channel, in Serra’s view, was “full of a huge number of formal pueblos, and the most wonderful land.” Serra, now a Catholic Saint, is a controversial figure in my hometown.

In the decade and a half that followed the establishment of the mission at Santa Barbara, according to one estimate, nearly 85% of the Chumash population relocated and settled under the supervision of the Spanish priests. A number of forces, working in unison, propelled this significant and abrupt movement of native peoples.

European diseases took their deadly toll, killing as many as two‐thirds of the Chumash living along the Santa Barbara Channel in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. During the same period, the enormous expansion in Spanish livestock herds compromised Chumash subsistence routines. Drought and fluctuations in sea temperature may have affected the availability of those resources upon which the Chumash relied for food. Fewer people facing significant subsistence crises, the loss of elders and ritual knowledge, and the critical numbers to maintain the integrity of their communities, the Chumash may have moved to the missions in an effort to insulate themselves from the frightening changes occurring in their world.

Once they arrived at the missions, Chumash villagers may not have seen any fundamental contradiction between their traditional beliefs and those taught by the Catholic priests. Missionaries dressed in ceremonial attire when they said mass, led their community in song, and performed sacred rituals, like their own religious leaders. Their knowledge of the sacred set them apart from the broader community. Like the Pueblos before them, Chumash villagers may have seen in the Spanish cross something analogous to the large prayer poles upon which they made their own ritual offerings. Chumash at the Santa Inés mission, for example, hung strings of dried fish and chunks of venison upon the large cross that stood outside the church. At the outset, Chumash villagers would have had little reason to view their traditional beliefs as being in any way incompatible with those of the priests. The conflict that followed was not inevitable, and as historians we need to hold Europeans responsible for the cruelty of their acts.

Once a group of Chumash villagers decided to relocate to the mission, it became more difficult for those who hoped to remain behind. Village economies collapsed, making feeding those who stayed even more difficult. Those who moved to the missions began working in the Franciscans’ fields, producing even more food and creating an environment where the missions seemed to offer both a source of subsistence and a community to which one might belong. But those who settled in the missions did not find relief. Death rates in the missions always surpassed birth rates. Between the years 1771 and 1820, according to one study, the average annual birthrate in the missions stood at 41 per 1000 mission Indians, while the death rate reached an average of 78 per 1000. Only two out of three children made it to their first birthday. Of these, 40% died before they reached the age of five. Few survived past their tenth birthday. Though few epidemics descended upon Alta California, chronic diseases such as dysentery took an enormous toll in Chumash lives. While the non‐Indian population reproduced rapidly, Indians succumbed in large numbers to illnesses in turn made more deadly by unhealthful living conditions, a brutal work regime, and, as one archaeologist noted, “the psychological impact of mistreatment in the missions and by cultural dislocation.” It is a horrifying story.

Those who received baptism and survived (the Spanish called them “neophytes”), faced rigid discipline. In an attempt to impose their own sexual morality upon the Chumash, the priests confined unmarried men and women, some of whom experienced sexual abuse at the hands of Spanish soldiers, in separate crowded and unhealthful barracks. The Franciscans punished any transgression of their moral code by the neophytes with brutal beatings, the use of the lash, solitary confinement, and mutilation. Officials in the imperial center thought this brutality was not only cruel but terribly backwards. Alta California’s Governor Felipe de Neve, as early as 1778 hoped to transform the Indians of Alta California into useful subjects of the Spanish Crown by guaranteeing them a rudimentary municipal government and some control over their own communities. Neve opposed the use of corporal punishment, and believed that missions, by isolating Indians from the gente de razon, the Spanish settlers, retarded their improvement. They should interact with colonists, learn Spanish, and assimilate into the empire. The Franciscans, led by Serra, defied these efforts with all their energy, preserving a religious institution that had fallen out of favor amongst the Bourbon Reformers who took control of the empire late in the eighteenth century.

The missionaries brutally exploited Chumash labor. The Chumash produced nearly everything consumed in or sold at the mission. They faced extraordinary limitations on their freedom. Still, Chumash men and women who settled in the missions seldom granted to the Franciscans all that the priests desired. Chumash elites continued to marry other elites, and those who led native communities outside of the missions often exercised leadership roles within. Chumash working in fields or tending Spanish livestock herds gathered traditional foods and hunted and fished as they always had done when the opportunity arose. Chumash herdsmen who worked too far from the missions to return every night established camps, like that at Saticoy near San Buenaventura, which became the basis for native communities.

Many neophytes clung to important elements of traditional belief. Some of the Chumash at Santa Inés continued to decorate prayer poles. At La Purisima, a twenty‐three‐year‐old man raised at the mission, and “instructed in everything appertaining to religion,” refused on his death bed to confess his sins and die “like a Christian.” Others ran away, joining Chumash communities in the interior where they reconstructed the social and familial relationships that always had given shape to their village communities. On occasion, the Chumash challenged directly the beliefs of the Franciscans. In 1801 a Chumash woman at Santa Barbara began to preach that non‐Christian Chumash would die if they received baptism. She had ingested datura, a hallucinogen that enabled Chumash travelers to encounter powerful spiritual forces in their cosmos. Like other prophets, she received a vision, and called upon her people to change their ways. The neophytes would suffer death as well, she said, unless they renounced Christianity, embraced their traditional beliefs, and washed their head with special water she called “tears of the sun.” The movement flashed brightly and spread rapidly, and Chumash people showered the prophet with gifts and offerings. The Spanish, clearly shaken, suppressed the movement the moment they learned of it. What, one frightened priest asked, would have happened had the prophet called upon her followers to kill the priests? The priests could not control the thoughts of the native peoples who settled in their missions.

More than two decades later, a much larger uprising took place. Discontent amongst the mission Chumash had increased, and Chumash leaders at La Purisima began sending bags of beads into the interior to secure allies against the Spanish. Rumors of revolt became widespread, even if the Spanish did not take them seriously. Neophytes at Santa Inés, La Purisima, and Santa Barbara hoped to launch a coordinated attack on Sunday, February 22, 1824, during the celebration of the mass. On the Saturday before the uprising, however, an Indian from La Purisima traveled to Santa Inés to visit an imprisoned relative. The Spanish guard refused to allow the visitor to see his relative, and after an exchange of words, the guard ordered the visitor whipped for insolence. The Chumash at Santa Inés fought back. They burned most of the buildings at Santa Inés, sparing only the church. They then moved to the complex at La Purisima, which they captured after a brief firefight. The victorious Indians strengthened their defenses and prepared to hold the mission indefinitely.

The next morning, Chumash at Santa Barbara under the leadership of Andrés Sagimomatsee seized control of that mission. Well aware that they could not hold it for long, owing to the proximity of the Spanish garrison at the presidio, they looted the mission and withdrew. Some crossed the channel to their old homes on Santa Cruz Island; the majority headed toward the Tulares, a five‐day march to the east in the interior. They found here shelter and a highly defensible location, establishing in effect a Native American maroon community that the Spanish could attack only with great difficulty.

The Chumash held La Purisima for nearly a month. On March 16, the Spanish attacked, exchanging musket and artillery fire with the defenders. The Spanish ultimately retook the mission, and sentenced seven of the rebels to death. Meanwhile, the Spanish marched to the Tulares. They hoped to persuade the rebels to return. At first, the Chumash refused. “We shall maintain ourselves with what God will provide us in the open country,” they said. They did not turn their backs on all the changes the Spanish had brought. “We are soldiers, stonemasons, carpenters, etc.,” they told the Spanish commander, “and we will provide for ourselves by our work.” They saw the crafts they had learned in the missions as tools that could help them sustain themselves as free persons. The negotiations continued and finally, according to a Spanish observer, “in peace, mutual joy and satisfaction, they were convinced to take advantage of the general pardon” the Spanish had offered them to “return to the mission.” When the Indians returned to Santa Barbara in June, the Franciscans felt that the rebellion had come to a close. But nearly 400 refused to return. They moved farther east, putting more distance between themselves and the Spanish. The uprising of 1824 was not simply a strike against the heavy‐handedness of the mission, but part of a movement by Chumash peoples to secure their independence, to live their lives in a changed world upon their own terms.

That’s why I told this story in a chapter dealing with the era of the American Revolution. Independence can mean many things. It is something most American identify with the Revolution. Americans sought independence from their colonial overlords. They sought “Freedom” from the British. Many Americans will argue that the Revolution was indeed founded to establish freedom and liberty. But the experience of hundreds of thousands of enslaved peoples, and millions of Indigenous people living on this continent, showed clearly that their own independence was never considered by American founders and European colonists. This country was born out of exploitation, and it was shaped by systematic programs of dispossession and colonialism.