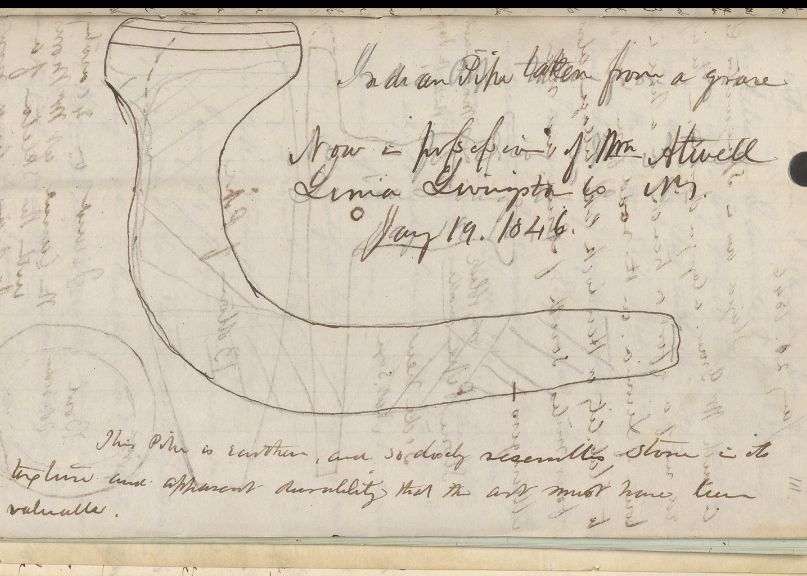

In January of 1846 Lewis Henry Morgan, soon to become the well-known ethnographer and a founding father of the field of anthropology, began a journey from his Rochester home south along the Genesee River. He visited friends along the way, collecting from them Indian “relicts” they had dug up to add to his already-considerable collection.

In the Genesee Valley town of Lima (pronounced like the bean, and not the Peruvian capital), Morgan stayed with William Brown, who told him about the three skeletons he recently had found on his farm, buried in a sitting posture, facing each other as if seated at the three corners of a triangle.

This bothered Morgan, for he had been told just eleven months before by the Onondaga sachem Captain Frost that Iroquois peoples never buried their dead in a seated posture. A contemporary of Morgan’s described Captain Frost as a man “of noble character, fervid eloquence, and unimpeachable integrity.” There was no one “as well-versed as he in the genius and policy of the ancient government and the conducting of good councils and in the practice and celebration of Indian rites.” Forced to choose between believing Captain Frost or William Brown, however, Morgan concluded that in this instance the Onondaga sachem must have been mistaken.

Morgan’s short travel account is fascinating. It shows us a man, interested in Indian “antiquities,” scooping up arrowheads, spear points, mortars, pipes, and human remains nearly everywhere he went in the aboriginal homeland of the Senecas. One could not disturb the soil, it seemed, without finding evidence that should have led to one obvious conclusion: that the part of New York where I live and work, the Genesee Valley, developed and grew into the Empire State only because of a systematic program of Haudenosaunee dispossession. White New Yorkers could not move a stone without uncovering reminders of the people from whom their own ancestors had taken the land.

IF YOU LIKE HORROR MOVIES, you are probably familiar with the old trope of the “Indian Burial Ground.” White people move into an area, treat the land and the human remains buried beneath it with disrespect, and bad things start to happen. In the movies there are frightening consequences. In real life, white Americans have built their towns, cities, and states on Indigenous homelands with nary a thought. They are interested in the Native American past only to the point where that history begins to cost them something. Americans have prospered precisely because they dispossessed Indigenous Americans. We think little of the soil beneath our feet. The sins we forget and the sins we ignore will never be forgiven.

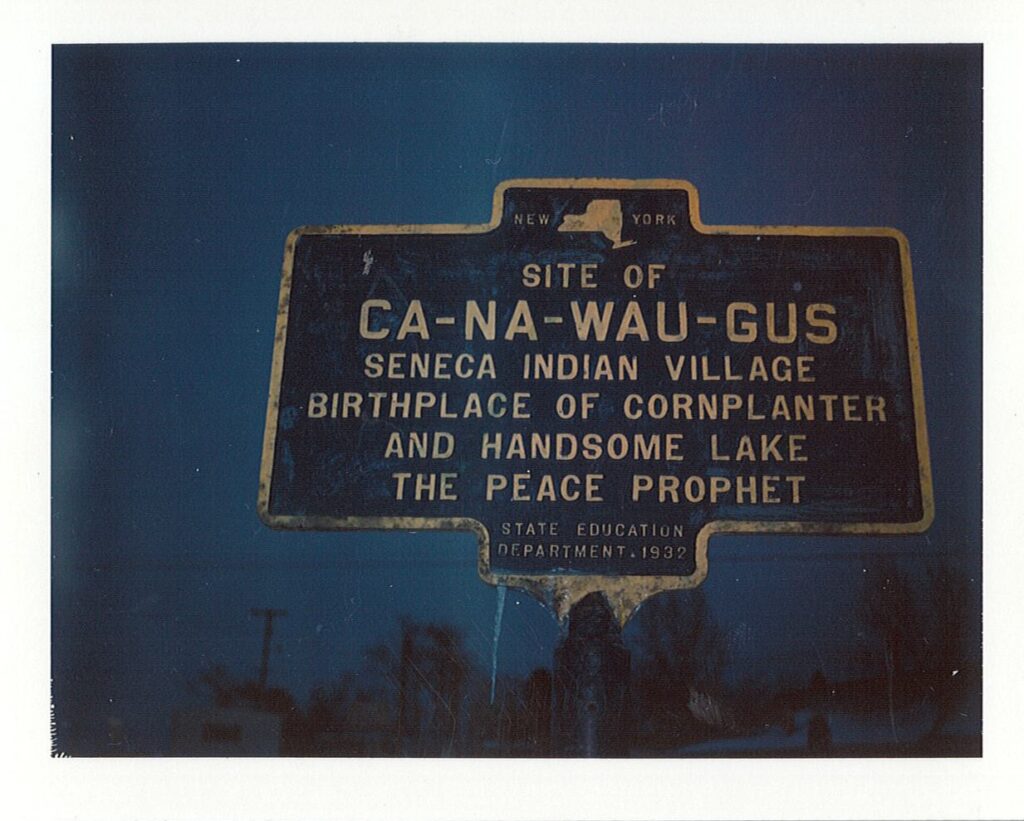

I HAVE THOUGHT ABOUT THE BURDENS AND OBLIGATIONS of the past quite a bit during this horrifying year. For all sorts of bad reasons, it has been a “historic” year, of course. Developments in my own work, however, have forced me to think more than I have previously about how the past can impose upon us a responsibility to set things right. Early in this pandemic season I became aware of a planned solar development for the site of Canawaugus, the Seneca town where important leaders like Red Jacket, Cornplanter, and Handsome Lake were born. Canawaugus avoided destruction by the Continental soldiers George Washington sent on a scorched earth campaign against the Iroquois in 1779, and it remained in Seneca hands as a reservation after the disastrous Big Tree treaty of 1797. White farmers worked the lands surrounding Canawaugus. Nearby towns, like Avon, grew up along the Genesee. Canawaugus slipped from the Senecas’ hands finally in 1826 in a corrupt bargain that violated the laws of the United States and that never received the required Senate ratification.

Then came this past summer the Supreme Court’s surprising decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma. There is a lot going on in the Court’s decision. The key point, included in Justice Neal Gorsuch’s majority opinion, is that reservations remain Indian land until Congress acts explicitly to declare that they are not. The passage of time could not eliminate a reservation, nor could illegal seizures of reservation land. This seemed to offer a means to challenge the 1826 transaction that took from the Senecas Canawaugus, their other lands scattered about the Genesee Valley, and big chunks of their reservations at Tonawanda, Buffalo Creek, Allegany, and Cattaraugus. The McGirt decision could lead one to believe that that vast amounts of land in western New York remain Seneca reservation land.

When the legitimacy of the title to lands that non-Indigenous New Yorkers claim is called into question, what must non-native people do? When history shows that what white New Yorkers have gained has come at the considerable expense of the Senecas and their longhouse kin, and when it is obvious that white Americans did not bother to follow the rules they established to facilitate that dispossession and grant to it a veneer of legitimacy, is there an obligation to set things right? Morally? Ethically? Historically?

Maybe you are familiar with Ibram Kendi’s recent book, How To Be An Antiracist. Kendi points out that to claim that you are not a racist, that you “don’t have a racist bone in your body,” is simply not enough. Racism is structural and systemic. Defeating it requires action, engagement, and commitment. If you lament racism, but do nothing, you help the racists. Kendi’s book speaks clearly and undeniably to those who recoiled from the Black Lives Matter protests that took place in cities and towns across the country earlier this year as too disruptive. It addressed realities made plain after the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. But it speaks as well to the legacy of dispossession. You cannot claim your hands are clean when you live on stolen land.

My college has committed itself to becoming an antiracist institution. Discussions have begun on how to make that happen. The campus community has focused thus far on Black Lives Matter and police brutality. These are current events and our focus here is understandable, especially after the police killing of Daniel Prude in March in nearby Rochester. I am glad we are doing this. But what about the Senecas, and the peoples of the Longhouse generally? What are we called upon to do to set matters right?

I teach at a college, after all, that stands on Native American land, the site of the largest Indigenous town in all of what ultimately became New York State. The college itself is located in a town founded by a man heavily invested in the notorious Ogden Land Company, for whom no practice was too foul to effect the goal of acquiring the Seneca reservations that remained after Big Tree. The illegal transaction of 1826 was the handiwork of the Ogden Company, as was the disgraceful Buffalo Creek Treaty of 1838, arguably the most crooked treaty in the history of the United States. The town of Geneseo, meanwhile, is the seat of Livingston County, named after the patriot leader who signed the Declaration of Independence. Follow the Livingston family tree up its branches and down to its roots and you will find Iroquois dispossession. My point here is clear. Our college could not exist were it not for Iroquois dispossession. If we truly want to commit ourselves to anti-racism, what are we going to do in the face of that extraordinarily well-documented history?

I am skeptical that we are ready and willing to carry the burden of anti-racism when it comes to Indigenous peoples. We fly a Haudenosaunee flag in the Student Union in a hallway where the flags of all our foreign students fly. I pushed for this for two years, and was pleased when the flag finally went up. Most Haudenosaunee people see themselves as members of polities apart and separate from the United States, and they deserved a place here, I felt . Still, as time has passed it increasingly bothers me as an

entirely inadequate gesture, for Haudenosaunee peoples are hardly “foreign” to New York State. They were here from the very beginning. The Haudenosaunee flag also stands on the stage during commencement and at other campus events. The campus community voted to commemorate Indigenous Peoples’ Day in place of Columbus Day, but we’ve done it so very quietly it’s as if we do not want anyone to notice. We do a territorial acknowledgment, but we do so in rooms where almost no native peoples are present.

I have raised these issues in the past. I get sympathetic nods. People tell me they are thankful that I raised these important issues. Little action has taken place.

So what do we do? We could fly the Haudenosaunee flag on the college flagpole, at the college’s main entrance, announcing publicly that we recognize our college stands on Indigenous soil. Improvement in curricula of K-12 social studies is badly needed. We could push for these essential reforms. We could do more to make sure our own students learn about the Indigenous history of the region in which they live. These gestures would cost us little. We could build this into the campus orientation. We could do more to remind students of the events that happened around them, and how it is that we came to name buildings on our campus after Red Jacket and Mary Jemison, and the Wadsworth family as well. Maybe it is time to consider renaming Wadsworth Auditorium.

We need to do more. We could make tuition, room and board free for Haudenosaunee students. We could do that for the cost of some of the SUNY system’s Division I sports programs. To the folks who say Division I sports is a primary vehicle for recruiting students of color to SUNY, I say that our problems then are deeper than you think, our commitment to diversity and equity more ineffective than even I had supposed. We could hire faculty from Haudenosaunee communities. We are in the midst of a terrible economic crisis–on our campus and in terms of our state funding–but if it is important we could make it happen. At the end of the day it is a choice.

We are not alone in wrestling with these questions of enormous consequence. Numerous stories about the complicated connection between Indigenous dispossession across North America and the creation of the nation’s land-grant universities have provoked important and painful discussions. My friend Jon Parmenter at Cornell is doing important research on the Morrill Act and his university’s connection to nineteenth-century dispossession. On some campuses, like Cornell, the awareness of this past has led to concrete steps to set things right.

SUNY and the State of New York should join in these discussions. The state and the university system owns a lot of land. Perhaps we the people could take steps to return some of that land to those from whom it was taken. We should, at least, invite the members of Haudenosaunee communities to come to our campus, to engage in a dialogue, where we listen and learn from them what in their view it will take to set things right.