Annie Dibo and Susie Porter came to Mrs. Jacobs’ house because she was dissatisfied with the two Rosebud Sioux women who preceded them. Helen Kimmel and Grace Burnett arrived at Mrs. Jacobs’ place in April of 1910, and stayed only until the middle of June. Helen was nineteen years old when she arrived, and Grace Burnett was eighteen. They stayed with her in Oak Lane but not long enough to make it out to the beach in New Jersey.

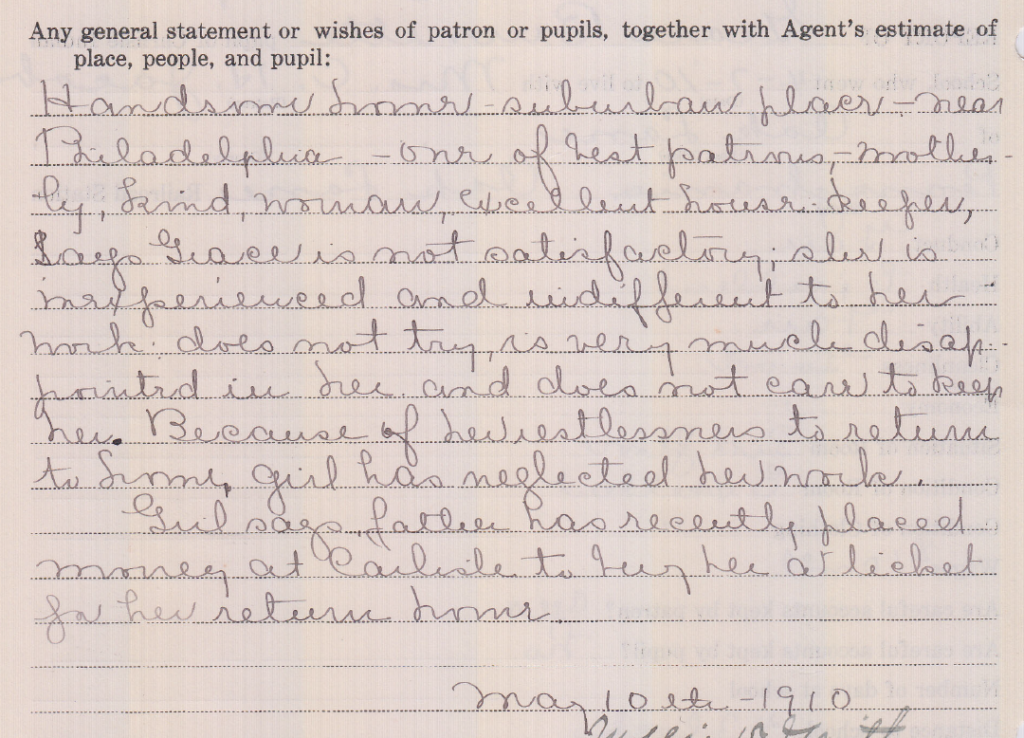

Mrs. Jacobs told the Carlisle agent who visited her that Grace was an “inexperienced worker,” and that she was “indifferent to her work” and “does not try.” Helen, Mrs. Jacobs reported, “has never been contented,” and “is restless and anxious to return home.” Helen, “who neglected her work,” because of “her restlessness to return home” felt that way because “her father has recently placed money at Carlisle to buy her a ticket for her return home.” Grace, as well, had received “a letter containing money from her father to return home.” By June of 1910, Grace was on her way home. Helen did not leave Carlisle until October.

In each instance, the school noted as the reason for the discharge of the girls that they failed to return from their leaves of absence in 1910. Carlisle’s staff expected them to return but they did not. At first glance it seems that neither of the girls wanted to be at Carlisle. They both seem to have been unhappy, and wanted to get home at the first opportunity. As always, it is more complicated than that.

Helen’s file is pretty slim. She responded to the school’s request for information from her in 1912. She was at Rosebud, keeping house, renovating her family’s home, and working on the ranch. The family had 160 acres, 20 horses, 10 head of cattle, and a cat. We know that in September 1913 she married Lancelot DeCory, a graduate of the Flandreau Indian School, and moved with him to Valentine, Nebraska. DeCory was “engaged in the automobile business in Valentine,” according to the Carlisle Arrow, “where he has many warm friends, all of whom join in extending hearty congratulations, and best wishes, for a long and happy wedded life.”

And they seem to have had one. Both Lancelot and Helen were active in their community. Lancelot died in1938, but they had kids, Claude and Lancelot, Jr., who fought in the Italian campaign during the second World War. Helen lived into the 1960s, a very long and fruitful life.

Grace said a bit more about her time at Carlisle. She returned home to her parents’ house at Rosebud, “one of the largest ranches around here.” She filled her time with baking, sewing, and beadwork “to earn my pin money.” She had experienced some great sadness. “I am motherless,” she said, “and my grandmother died a year ago in July of 1911.” She had no women relatives and now wanted to return to Carlisle to graduate. She did make it back for a short stay.

She had hoped to return to Carlisle in the fall of 1912, she wrote in a letter dated January of 1913, for “now I am only an ex-student, and it is all my fault.” It wasn’t, and Grace was surely too hard on herself. “I wanted very much to return to Carlisle this fall,” she wrote, “but I could not, as there was lots of work to be done on our ranch and ‘hired men’ are scarce just about that time, so I had to help.” She did not get free until mid-December, and by then it was too late. So she kept doing housework, and spent her spare time riding horses, sleighing, and ice-skating. She said that she “got lonesome for Carlisle every time I read The Arrow, but I can’t do without the little paper.”

The Carlisle applications are a standardized document. They include a set of “endorsements” listing “the laws relative to the transfer of Indian children from reservations and schools.” The United States Statutes-at-Large said that “no Indian child shall be taken from any school in any state or territory to a school in any other state against its will or without the written consent of its parents.” Children could not be sent to a boarding school without the consent of his or her family, “and it shall be unlawful for any Indian agent or other employee of the government to induce, or seek to induce, by withholding rations or by other improper means, the parents of next of kin of any Indian to consent to the removal of any Indian children beyond the limits of any reservation.”

It is not unreasonable to assume that laws like these existed for a reason, and that laws were intended to prohibit practices used to coerce Indian children to attend boarding schools. It does not take a deep dive into the records to see the heavy-handedness of federal policy makers. No doubt there was coercion employed at times and in places, and there were students whose experiences at Carlisle were horrific. Despite these cases, many students, and students’ families, saw much of value in a Carlisle education. These students, even when they felt lonely and ached to get home, missed the school greatly once they got home, and often they wished they could return.

This makes the story of Carlisle a difficult one that defies easy categorization. Different students had different experiences. We need to be careful how we talk about the boarding school experience. More news stories appear each week detailing horrifying tales of abuse and death. Just last week the New York Times ran a story about the Genoa Indian School under the headline of “Researchers Identify Dozens of Native Students who Died at Nebraska School.” Carlisle and the other boarding schools will give up their stories some day. We must prepare ourselves for stories that are complicated, full of heartbreak and cruelty to be sure, but also deeply ambivalent. Some Carlisle students loved what many of us wish they did not.