I am teaching this semester a freshman writing seminar called “The Lost Colony.” The students are reading an e-book version of David Beers Quinn’s The Roanoke Voyages, 1584-1590, which is now available from Routledge, and a copy of my book, The Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand.

For the first week of class I wanted the students to recognize the extent to which our understandings of the Roanoke ventures, and of early European expansion generally, are encrusted with a deep layer of myth. In the past, I had the students read Paul Green’s play The Lost Colony, published by the University of North Carolina Press. If you are on the Outer Banks in summer, by all means, slather up with bug spray and head on out to catch a performance. It has changed over the years. But the original 1937 version has not aged well, and I just could not subject myself, or the students, to that dreadful thing again. So we talked about “In Search Of,” a show I watched as a kid and that was hosted by Leonard Nimoy, and the recent “American Horror Story” series that connected some way back to Roanoke. Not much of an improvement, but I think they caught my drift. Usually I mention David LaVere’s book on the goofy Dare Stones excitement in the 1930s, The Lost Rocks. It’s an entertaining read, even if I do not agree with everything in the book.

Virginians claimed credit for the first successful settlement on American shores. They arrived in the muck they called Jamestown in 1607. The Pilgrims who set their feet on dry land at Plymouth Rock in 1620 received lots of attention, too. But North Carolinians, late in the nineteenth and early in the twentieth centuries, argued that they deserved some attention, too. It was at Roanoke, as speaker after speaker, and writer after writer claimed, where the first English child was born on American shores, and where the first baptism to English Christianity took place. (To suggest that Americans look at the history of St. Augustine during these years was unheard of). So I had the students read a collection of speeches that dignitaries delivered on Roanoke Island in 1907 to commemorate that glorious history, Thomas Pasteur Noe’s Pilgrimage to Roanoke Island.

According to Francis Winston, the lieutenant-governor of the Tarheel State and the event’s headliner, Roanoke was the opening chapter in “the story of the human race seeking liberty.” While nobody who has looked at the surviving documents from Ralegh’s Roanoke ventures would agree that freedom mattered to the colonial promoters at all, Winston asserted that “the people who laid the foundations of colonization in this New World, were nearly all refugees, exiles, wanderers, pilgrims. They were urged across the ocean by a common impulse, and that impulse was the desire to escape from some form of oppression in the New World.” And, of course, to escape that oppression, Winston wrote, the freedom-seeking adventurers encountered the region’s native peoples, “the savage red man, happy and free, in possession of fields, forests and streams.”

He roamed at large, a king among the beasts of the forest, but at best himself only an improved animal. Before this all-conquering race, he is gone and gone forever. He fulfilled none of the divine commands. He did not hunger and thirst after righteousness; he was not poor in spirit, nor pure in heart, nor meek, nor merciful. He could not inherit the earth. God’s law is a law of service. That race shall survive and inherit the earth, which renders to the earth the greatest service: service of daily lives employed in useful labor, of hearts filled with love and unselfishness, of souls inspired with noble ideals, of heroic self-sacrifice and devotion to the higher interests of humanity. The Indian is gone. The Negro is going. The white man will survive in fulfillment of the laws of God. There is no room on earth today for vicious, incompetent and immoral races. White civilization is triumphant, because it is best; Christianity will rule the earth because it is a religion of love and service. The cannibal races of Africa, the idolatrous races in Asia, the savage Indian and the semi-civilized negro in America must all learn the laws of God, and fulfill them in their daily lives, or else pay the penalty of decay and final extinction.

That’s pretty racist, right? But not all that far removed from the sort of stuff that those of us who teach Native American history hear all the time. Listen to your favorite right-winger on the radio talk about Columbus Day. Or listen to Ben Shapiro, the knucklehead-hipster-conservative-pundit, who said as much about Native American cultures last October. These views are deeply held, deeply entrenched, widely-believed. That Indians are doomed to disappear, are already gone, or are somehow inauthentic when they remind white Americans that they still are here, are beliefs too many Americans share. What Lt. Governor Winston said in 1907 about the Indians who once had lived on  Roanoke Island has been said about Indians nearly everywhere throughout American history. Including Virginia. (Check out Brian Dippie’s old book, The Vanishing American, for examples of what I am talking about).

Roanoke Island has been said about Indians nearly everywhere throughout American history. Including Virginia. (Check out Brian Dippie’s old book, The Vanishing American, for examples of what I am talking about).

The same week that my students read Noe’s collection of speeches from Roanoke Island, came word that Congress, after many, many, years, had enacted legislation to extend federal recognition to six Virginia Indian tribes. Congress passed a law in 1978 providing a process for recognizing and acknowledging Native American tribes, and that process is described in Native America, but Congress, with plenary authority over Indian affairs, can also enact specific legislation recognizing an American Indian community. The Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017, which Congress sent to President Trump on 13 January, extends “Federal recognition to the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Chickahominy Indian Tribe–Eastern Division, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, Inc., the Monacan Indian Nation, and the Nansemond Indian Tribe.” This is significant legislation, and I am hopeful that the Crown Prince of Mar-A-Lago will find time in his busy schedule to sign it into law. But he might do even more.

Several decades ago, the great anthropologist Helen C. Rountree (nobody has written more on the Powhatan Indians of Virginia and their descendants) titled one of her studies Pocahontas’s People, a history of the Powhatans. The six tribes named in the Thomasina Jordan bill are all part of that broader community. President Trump, as readers of this blog will understand well, has regularly referred to his opponent Senator Warren as “Pocahontas.” It is racist and unacceptable. As I wrote in February of last year,

For President Trump, it seems, Native American identity can be determined by a quick glance. He looked for certain characteristics and did not see them in the Pequots, or in Senator Warren. Centuries of intermarriage, enslavement, and the complex, messy, and tangled history of native peoples mattered in his determination not a bit. For him, native peoples were individuals with certain easily distinguished racial features, and not members of political entities that possessed an inherent but limited sovereignty that predated the creation of the United States.

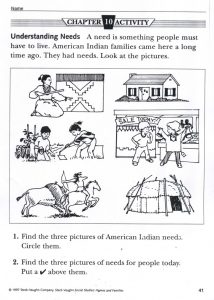

But here’s the thing. Too many Americans share Trump’s views about who Indians are and what they ought to be. Too many Americans view Indians as part of the past. Think about the most commonly held stereotypes about Native Americans: What images enter your mind? Ask your friends what they think. Chances are a lot of those images come from the past.

And when we speak of Native Americans as being part of the past, we are aiding in an ongoing colonial project which erases native peoples in the present. And if they are viewed as part of the past, or inauthentic, it becomes easier to dismiss the legitimacy of Native Americans, as individuals and as members of semi-sovereign nations, as being out of time and place and, as a consequence, irrelevant. It becomes easier to ignore the very real problems of inequality and injustice in Indian Country; it becomes permissible to cheer for a football team with a racist name; or to silently assent to a President’s decision to authorize a pipeline through lands that a Native American community deems sacred. It also makes it possible to call into question the sovereign right of native nations to develop their economies, protect their lands, and against immense odds preserve their cultures. When the President casts Indians as part of the past, he makes it more difficult for many Americans to recognize the importance of native peoples’ calls for justice today.

I wonder what the President will say if he holds a signing ceremony. I wonder what words his speechwriters will place in front of him. Will he invite representatives from the tribes to the White House? President Trump has been in office for just over a year, but the contempt he has shown towards native peoples is unmistakable. He has an opportunity, should he choose to use it, to explain that his name-calling was destructive and racist, that native peoples are still here, that they are still an essential part of the fabric of American life, as vital and important to this nation’s past and present as they ever have been. He can explain to Americans that native nationhood matters. He can show that the views expressed by Lt. Governor Winston, so widely shared 110 years ago, and shared still by too many Americans and by himself, were wrong and remain wrong. He can show the American people that native peoples are still here, and that their historical experiences matter. I am not optimistic that he will be able to do that.