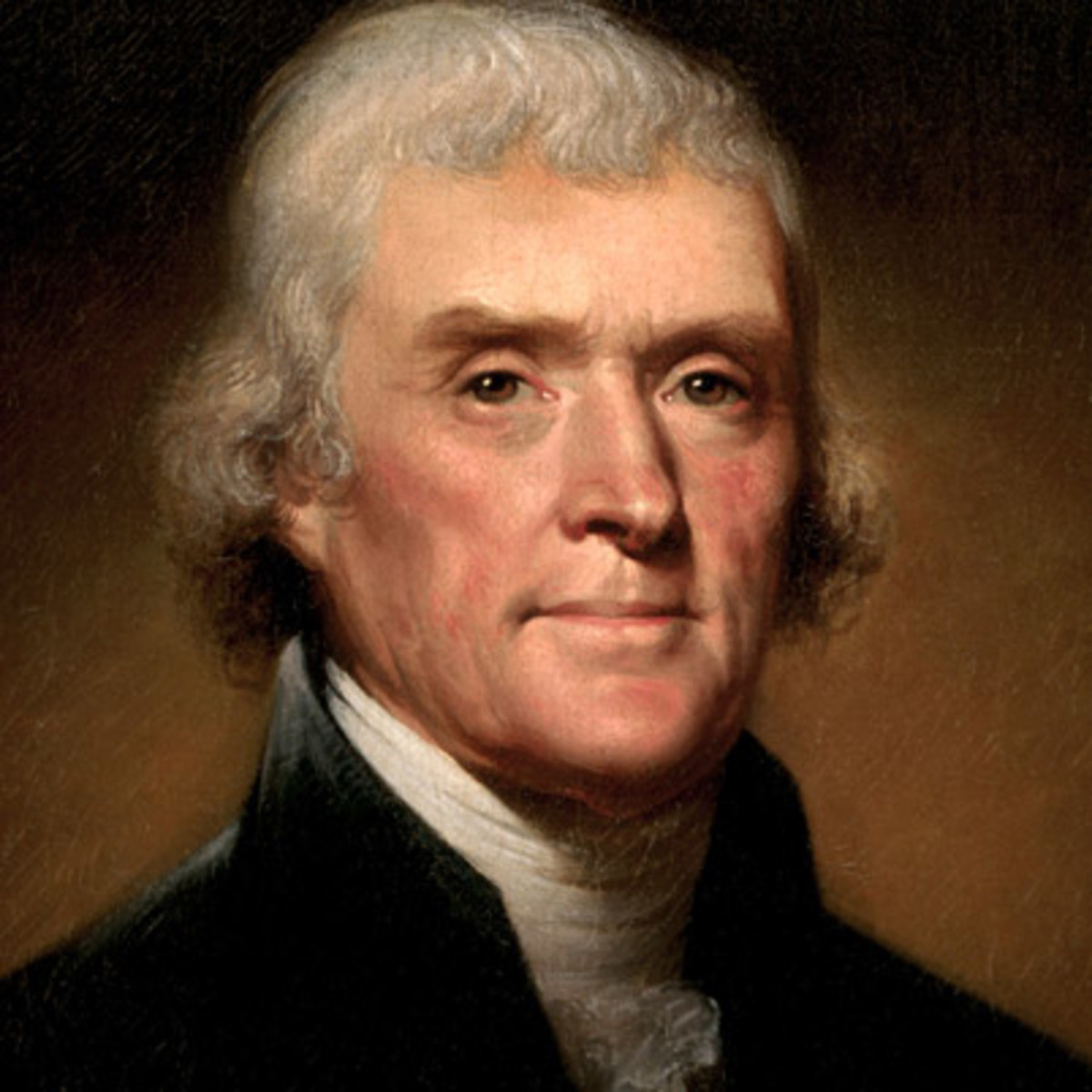

You have probably seen the news. The New York City Council voted unanimously this week to remove the seven-foot-tall, 100-year-old statue of Thomas Jefferson from their chamber in City Hall. The statue of the founder of the University of Virginia, and the author of the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom and the Declaration of Independence, will be relocated to the New York Historical Society, which pledged “to present the statue in a historical context that captured Jefferson’s legacy as a founding father, but also as a man who enslaved more than 600 people and fathered six children with one of them, Sally Hemings.”

It’s Jefferson’s treatment of enslaved people that has caused this reassessment, but that is only part of his record. I have written about Thomas Jefferson’s policies toward Native peoples on this blog. I hope you will take a look at that piece again. In our current period of refreshing historical revisionism, Native Americans are still too often left out of the equation. On a stolen continent, that is unfortunate.

The City Council’s action has provoked the expected response from the expected people. Donald Trump, the former president, chimed in from wherever the hell he is these days, with a predictable denunciation of all things on the left. “The late, great Thomas Jefferson, one of our most important Founding Fathers,” he wrote, “and a principal writer of the Constitution of the United States, is being ‘evicted’ from the magnificent New York City Council Chamber.”

Jefferson, of course, had nothing to do with the Constitution. He was in Paris when it was written. It is not the first time that Trump has made historical errors and it will not be the last.

Look, even though this statue is being relocated, historians will continue to teach and write about Jefferson, and students will learn no less about him than they did previously. This is not an “erasing” of history. It is a revision. And it is fundamental to the historical enterprise.

American history is being revised all the time in scholarship, but also in public spaces, in the streets, and at sites of commemoration. As this latest story shows, it also is taking place in city hall chambers. A statue of Jefferson is, in a sense, a historical argument–a statement on an American leader’s worth, on his accomplishments, and on his failures. Acts of vandalism committed on Columbus statues, and votes to remove statues of dead presidents, are commentaries and rebuttals to interpretations of the American past that individuals and groups now find objectionable.

History is such a fraught subject—it always has been, but now, especially so. It matters. And the work historians do is often implicated in assaults on what makes this country great, a menace to what the Boston Review called the “fragile patriotism of the American Conservative.” If only we would stop harping on the bad stuff.

So let me give you a definition: for those of us who are historians for our living, history is the study of continuity and change, measured across time and space, in peoples, institutions, and cultures. That is a definition I use a lot. It is one I share with my students regularly. History is not a science, but it is a discipline. When we do our work properly, I tell my students, we ask questions about the past, we dig like badgers for the evidence we need to answer these questions, we examine and assess this evidence with our eyes, ears, and hearts open, and then try to present our answers with a measure of grace and style. We must be truthful and honest, always, when it comes to this evidence. That is fundamental. We want to persuade you that our answer is right, our thesis correct, and our questions important. Sometimes we succeed. Sometimes we fail. The measure of the effectiveness of our arguments must be the quality of the evidence and the strength of our reasoning.

As a result, history can be a brutal business. We question everything. We are not in the business of telling you what you want to hear. History can provide us with an explanation for what happened, why, and the difference it made, but it seldom provides us with comfort, and solace, and your cherished myths will find no shelter with us around. It can be dark and violent and, at times, filled with heroism and bravery indeed, but there is also deceit and evil. When the great ancient Greek historian Thucydides wrote in his history of the Peloponnesian War, that “war is a violent teacher,” it was for him not a comforting story at all, but one of the darkest, most brutal depictions of human nature to appear in the western tradition.

And about those questions that historians ask. When I was taught long ago how to be a historian in my research methods class at California State University at Long Beach, my professor emphasized the importance of objectivity. Several years later, one of the professors that I studied with at Syracuse wrote at length about the historic emergence of objectivity as a value in historical scholarship. Many of those who criticize our work may raise objections that we are biased, and driven by our agendas to predetermined outcomes, that we lack objectivity. That is the point that I suspect Donald Trump was trying to make, however awkward the execution. Bias and prejudice and ideology can indeed cause the undisciplined student of the past to ask loaded or bad questions, or to read the evidence in a distorted manner, to make it say things that it does not say. That is bad history. But our preconceptions, as well, which we can think of as the lenses through which we look at the world, color our perceptions of what is good and bad, right and wrong. They are the lenses through which we see the world.

The point I would like to make is that all historical writing, whether it is the essay assigned you by teacher or professor, or a term paper, or a doctoral dissertation or a book, is an attempt to answer a question. And whether we are on the right or the left, the questions that present themselves to us as historians—that strike us as important, and worth answering, and worth investing all the time, travel, expense and energy to answer, come to us from our experiences in life, and in the archives, from our hard work, and, quite often, from our sense that all is not well.

Doing history well forces us to always be willing to reconsider our assumptions, and sometimes it involves so profound a reassessment that it becomes difficult to abide, for example, the continued presence of statues or monuments commemorating a particular part of the past. These statutes—these monuments—are texts, right? They make a claim, state an assertion about the past. They argue for the significance of this, or that, or another person, place, or thing. They offer an interpretation, and the assumptions and the evidence behind those assertions—it is our job as citizens and scholars to question them.

If you want to keep statues of Thomas Jefferson around, make your case. Engage in debate. Some good historians with whom I probably disagree on many points made their arguments. Not many of those who want to preserve these statues are willing to do that. Like the former president, they whine about being cancelled. One of the many problems plaguing this nation is a steep decline in the value placed on free and open debate. You want to keep Jefferson, others don’t. Let’s have an argument. Let’s urgently engage in some good, old-fashioned, unsettling Socratic dialogue.

I think back to a Pew Research study that was released in the summer of 2019. According to the data, the percentage of Republicans who saw value in a college education fell from 53% in 2012 to just 23% in 2019. Nearly 80% of Republicans believed higher education is headed in the wrong direction because of professors bringing their political and social views into the classroom. Republicans were far more likely than Democrats (73% to 56%) to assert that the problem of students not receiving skills they need to succeed in the workplace is a major reason why higher education is headed in the wrong direction. And three-quarters of Republican respondents felt that rampant political correctness is a significant problem.

As someone who has spent the last three decades on college campus as a student and a professor, I have some thoughts on this. All of my time has been spent at non-elite institutions, all but the four I spent in graduate school at Syracuse in public institutions of higher education. With the exception of one year at the University of Houston, I have never taught at a college with a doctoral program. And all my time in higher education has been spent in departments of history. I will speak of what I know first-hand.

It is true that the history profession as a whole leans leftward. There are a couple of points that need to be made about that. First, it is not that the academy chooses professors on the left; rather, it is people on the left who tend to choose academia. There is something about this constituency for whom years of education, the isolation and hard work of graduate school, the meager pay and the likelihood of never finding tenure-track employment, are not insurmountable obstacles. Many of them want to serve. They want to teach.

But more importantly, let’s say that you are a student in my Native American history course. Politically, I lean to the left. You can see that in many of my blog posts here. How might my course in Native American history be different from an identical course taught by a conservative professor? I have had this conversation before. I will emphasize the “bad stuff,” you might suggest, and cast American history in a negative light. Maybe I will beat up Thomas Jefferson. I may leave out any of the positive things in Native American history. OK.

What are those good things, I might ask? Could you name some of them? In Native American history? And are the negative things I mention in class, or in the textbook this website is intended to accompany, incorrect as matters of fact or interpretation? Have I not played by the rules? Have I ignored the canons of the historical profession? The truth is that how I teach my course, and how a Conservative might teach a course in Native American history, should not differ much if we both pay equal attention to the standards of argumentation, research, and evidence that serve as the canons of the discipline of history.

The point, you see, is not that a historian might bring his or her political and social views into the classroom. Some do, and they do so excessively. Some Conservative professors do too, like the Iraqi Seventh-Day Adventist at my old school in Montana who regularly told his students that African Americans were moving to Billings because it was easier there to commit crimes, or the self-professed expert on the history of lynching who told his students there was absolutely nothing objectionable about Lee Atwater’s infamous “Willy Horton” ad.

And as for preaching and indoctrinating? Relax. I can tell you that there is no way to lose an audience of 18-22 year olds faster than to be that old dude up there preaching. A better question involves asking how my prejudices and biases and interests and concerns shape what I present to my students. If you are willing to cry out that “Leftist” professors are indoctrinating their students, my reasonable response would be to ask you to prove it. Nor is it unreasonable for us to ask you to make a case as to where you think our interpretation is wrong. I will gladly listen to you. But at a certain point you need to put up or shut up. We all do. A historian without evidence is as useless as a pundit.

And when you tell me where you think I went wrong, I will also ask you questions. That is entirely fair. That is what a Socratic style of teaching is all about. These questions are designed to help you sharpen your thinking, to explore elements of your argument you may have overlooked, to consider your position from another perspective. I am also asking because I want to give you an opportunity to educate me. If I am honest, I must admit that I can learn from all my students, whatever their background, their religion, their politics. And by asking you to explore your own thinking, you learn in ways that you cannot from rote memorization, the type of soul-killing education still taking place in high schools across the country. We will ask you how you know what you claim to know. We will ask you, “What is the evidence that supports that claim?” “Why do you believe what you believe?” Sometimes, and just sometimes, in the face of questions like these members of our audiences will feel like they have been silenced. This is not censorship. It may be insecurity. Or a discomfort about engaging in debate. It is also possible that it is a simple matter of them having little interest in learning, and not having much worthwhile to say at all.