Four years ago I delivered the Opening Convocation address at SUNY-Geneseo, when you began your college careers as first-year students. This spring, with no pomp but plenty of circumstance, you will graduate, and begin to make your way in a world that looks very different than it did just eight weeks ago. Sitting at home, learning new ways to teach, and listening to the challenges you all have faced as your college careers wind to a close, it seems like a good time to revisit what I said to you back in the fall of 2016. So much has changed. I receive emails from students: one, who sits in her car in a McDonald’s parking lot and another, outside his old high school, to get access to the Wi-Fi they do not reliably have at home. Another cares for his parents, infected with the Coronavirus, looking after them as he tries to do his school work. He emailed and said he is sick now, too. Students who have lost family members and friends to this terrible disease, or fallen ill themselves. Students trying to find workspace in crowded houses, or who worry about the financial toll this crisis has taken on their families. I spend much of my time thinking about my students. I worry about you. Like a lot of people, I suppose, I get antsy and frustrated, and miss life before the pandemic.

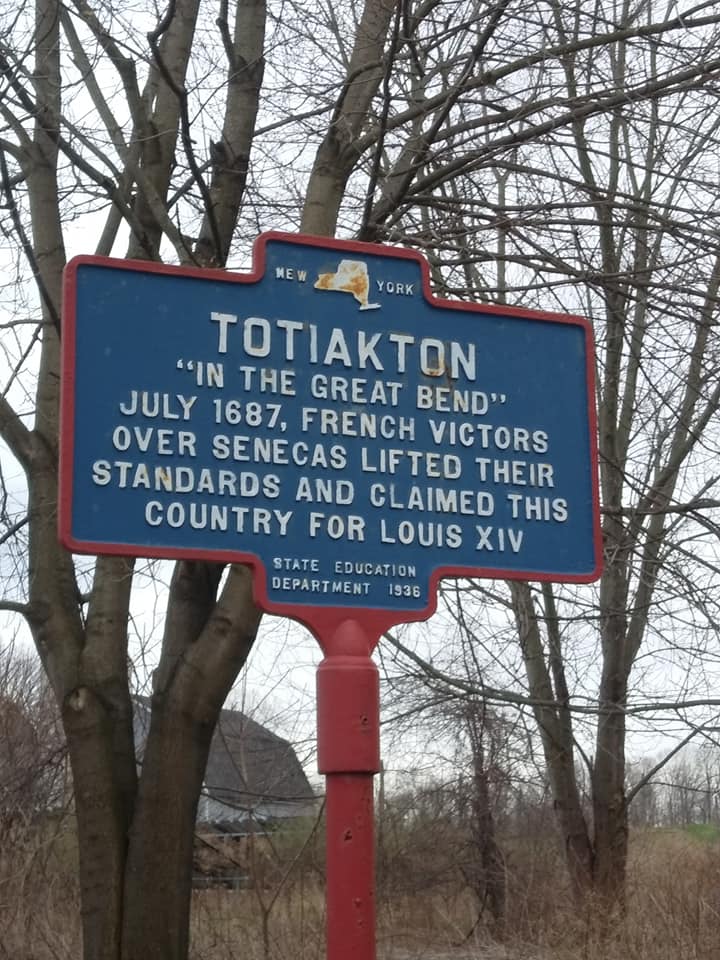

During the time our campus has been closed, I have walked a lot. I teach Native American history, and live in a region with a rich history. Geneseo, the small town where I teach in western New York, shows up in the historical documents long before Rochester where I live existed, long before Monroe or Livingston counties, long before there was much of anything European established in what became the broader upstate region. It lays in the heart of the ancestral homeland of the Senecas, the keepers of the western door of the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois longhouse. Seneca soldiers and diplomats who lived in this Genesee valley played a role in the history of two empires, the French and the English, in the Iroquois League and Confederacy, and in the history of the native confederations that threatened the existence of the British Empire in America and then the young United States in the 1790s. They continued to live in this valley, at least some of them, even after Major-General John Sullivan led Continental forces through the Finger Lakes in 1779, burning crops and villages, and scorching the earth, as he went. They were here in the 1790s and into the 1800s, before they moved to Allegany and Cattaraugus and Grand River in Canada. I have walked the hills around Ganondagan, and Totiakton, trying to breathe in some of the history in which I live. It is simple and inexpensive therapy.

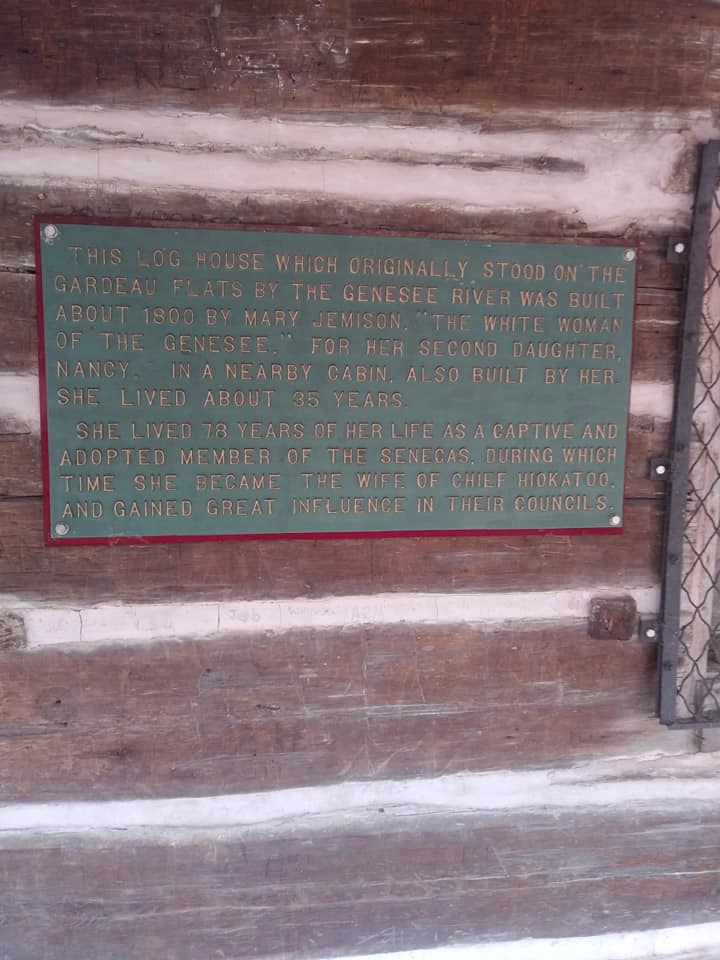

Stories from the past. I have told so many of these to those of you who have enrolled in my classes: about Mary Jemison, the white woman of the Genesee. She lived for a time as a captive, and adoptee, a refugee, and a Seneca homesteader down the road from the college in what became Letchworth State Park, where you can see a statue of her and a replica cabin. There are some documents with her mark on them in the county courthouse at the end of Main Street, a short walk from my office, where she deeded Seneca lands she claimed to white men associated with the Ogden Land Company, among whom numbered one of Geneseo’s founding fathers. Her Seneca sons, who died violently, two of the three at the hands of their brothers, victims of the alcohol that could cut jagged holes in the fabric of Native American life. There are New York State historical markers all over this county. Biased, to be sure, but all telling historical stories about this part of New York State.

For nearly two decades, I have told stories like these to students at my college. I have taught a lot of students over the years, and told a lot of stories. I am interested in the past, and its connections to the present. How things came to be. Continuity and Change measured across time and space in peoples, institutions and cultures. But all of that is just a way of saying that I am a guy that makes my living by asking and answering questions. And I love the questions—the search for evidence, the complexity and the lack sometimes of definitive answers, and the stories—the stories are at the heart of all that we historians do as teachers and writers.

Your last year in college is ending so differently from what you may have hoped or imagined, as you begin to write the next chapters in your own stories, of continuity and change, of being and becoming. You have become over the past four years more competent and more capable. You have developed your native generosity and compassion. Some of you are ready to take on any challenge, and some of you are frightened, worried and uncertain, sometimes for reasons that go deep into your family’s past, layers upon layers of stories you have to disentangle in order to understand yourselves. Some of you do not know what your story is going to look like, or how to begin writing it. We can hardly fault you for your feelings of existential dread, that the world’s a mess, and that the adults in the room have little to offer. Yet whatever you are feeling, I believe deeply that you can do so much to make this world—our world—a better place. You may be our best hope.

Four years ago I tried to convince you of the importance of cultivating intellectual fearlessness, the courage not to shy away from those things that seem to you–to all of us—to be extremely difficult. To master basic skills, of course. To be honest, curious, inquisitive, and relentless to be sure, but most of all, in terms of the questions you ask, the evidence you consider, the ideas you engage with, and the theses you advance, to be as fearless as you can be. Now, in this new world, so different from even the recent past, more than ever.

I teach at a liberal arts college. We wear that label proudly at Geneseo, and I think many of our students do, too. But that is a difficult thing. You have been asked for years, “What are you going to do with that degree?” Sometimes those questions can come from innocent curiosity, like, really, what are you going to do with that degree. But these questions can also come with a barbed tip, too, in the sense that the liberal arts and humanities are thought by some people to have limited value because, unlike the STEM fields and business, the liberal arts are too often thought of as adding little of value. You do not have to travel far to hear the pursuits to which you have dedicated much of the last four years denigrated by self-proclaimed “thought leaders” and “change agents” who have so much less to offer than they believe.

And that is too bad, for the study of these fields adds a lot. They give us the cultural capital necessary to participate in a democratic society in a meaningful and constructive way. But thinking in terms of nuances, complexities, ambiguities, shades of grey; being one of the people who embraces the big questions, pursues the answers over the long haul, who appreciates the value of open debate and discussion, who endeavors to find truth, and digs like a badger for answers—people like that can find these times we live in rough sledding. People who ask fundamental questions about why things are the way that they are and how they ought to be—they can be perceived as threatening to those in power, and they may often feel like they are bashing their heads against a wall.

You now live in a world, after all, that my generation and my elders have helped to create for you where too many people confuse their feelings and their fears for facts, where being smart and engaged and critical and willing to ask questions can make one an object of scorn. You live in a world as well where complexity is so often dismissed, where big and difficult answers to the big questions are avoided, that asking these sorts of questions can take a certain amount of courage.

In 2020 you look out on an America where you will see too many people who simply do not invest their time and energy to ask questions and stay informed. When we have a President who consistently says things that are not true, and a press that is more concerned with ratings and clicks than in pursuing difficult stories, we arrive at that dire point where the use of “alternative facts” can really be a thing we talk about with straight faces. We, the adults in the room, collectively have modeled some very, very, poor behavior. We reason sloppily or lazily; we are dishonest, or cynical; too many of us are cowards and grotesquely ill-informed.

We live in and have helped to create a world where—when we stand up in the face of the problems before us and ask, “Why?” and when we insist on a reasoned and relevant response to that simple question—it’s like an act of subversion, and subversive acts, even the smallest ones, require a degree of courage, of fearlessness.

We are also complacent in the face of inequality and injustice. Meanwhile you have seen continued gun-craziness, racism, rising anti-Semitism, fear. You see many Americans choosing to live in fear: of immigrants and Islamist extremists–but a plastic surgeon botching your operation is more likely to kill you in the United States than a terrorist. Peanuts kill more Americans than terrorists, as John Oliver pointed out. Armed dingbats arrive at Michigan’s capitol building, armed to the teeth, protesting the suggestion that they stay home to slow the spread of a pandemic that has killed so many. They are afraid, and they are not thinking deeply. People around the globe and in this country—some of them, anyways—seem to have more confidence in fear and anger and hate than in their opposites. With malice towards many, and charity for few; with little interest in heeding the call of the Old Testament prophets to seek out injustice and correct oppression.

You are part of the Massacre Generation. School shootings have been a reality since before some of you were born. You witness violence and hatred: White supremacists marching in New Orleans and Charlottesville to protect monuments explicitly commemorating white supremacy. Entering college on the eve of what many of you anticipated would be the election of the first woman President, you saw instead the ascent of an incurious “Reality TV” star who has at various times insisted that freedom of the press does not allow the press to criticize him; that torture, specifically prohibited by American laws, should be brought back; that we should wall ourselves off from the rest of the world; that women are objects who can be grabbed and groped at his pleasure; that ingesting disinfectants is a possible cure to the pandemic he supinely watched take over the country he was charged with governing; that the norms and values and responsibilities of civil society and basic ethics simply do not apply to his family and favorites, and that he has total authority with zero responsibility. And so many of his followers—frightened, violent, and clinging to a degenerate variety of Christianity uninformed by mercy, grace, and love–continue to degrade American public life.

Reasoned, humane, and just public policy is simply impossible without an informed, engaged, and rationally-thinking public willing to ask tough questions.

In other words, you all have come of age in this moment where a lot of really old issues—race and inequality and class and gender and violence and justice, are resurfacing in complicated and anguishing ways. The pandemic in new ways has exposed very old inequalities and power structures that benefit the few at the expense of the many. The problems are out there. They are so apparent. But to name them and to ask, “What can we do?” and to gather the information to solve them, can be tough. And so many of these problems we face are rooted, in part, in a rejection of critical thought, in an embrace of the irrational, and a society with these problems can fall prey to demagogues with their simplistic answers, and will find it difficult to display emotional maturity, and will be prone to violence. You have seen it. In front of one state capitol building, it seems, after another.

What are we going to do about all of this? To make America great again, or as great as it might be, we are going to have to rely upon you, and you are up for the challenge. I’ve been speaking to young people like you for more than two decades. Believe me. Those like you with a solid grounding in the liberal arts, whatever your majors, will best see that “injustice anywhere” just may be a threat to justice everywhere. And that if it is “an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny, that binds us, one to another,” as Martin Luther King once wrote, that you may be among those best suited to do something about it.

You do have power. I have seen it over the past four years. I am thinking of so many of my students as I write these words. Teachers will tell you that our students change us and, if we let them, they can make us better.

It takes courage to trust and to respect and to appreciate, as well as to care and to love, and to accept the validity of ideas presented by those with whom we would be predisposed to think we might disagree. To never underestimate others, to take people seriously, whoever that person happens to be, to accept the possibility that those with whom we disagree might have a point and, indeed, to admit that we might be wrong. To appear vulnerable in the face of those who despise us. It is not an easy thing for us, and it is not an easy thing for our students. It takes courage, and a willingness—a true commitment—to approaching everything and everyone with a readiness to see goodness and to be surprised.

It is so easy to feel like the challenges we face are too big and it is possible, I think, that we all feel at times like we are not enough to make a difference—that we need to be wealthier or have more expertise or access or a stronger prescription or whatever. But what if we used our skills and our thoughts and our reason and acted as if we were exactly what was needed? If we all knew we could work to close the gap between the way things are and the way things ought to be, even a little bit, would we have the courage to act? Would we really do it?

I believe you can.

A long time ago I had a great history professor. His name was Albie Burke. He died about ten years ago. And even though I left Cal State Long Beach where he taught in the late 1980s, I still got back to campus every other year or so to have lunch with him and to catch up, to talk about the Supreme Court, constitutionalism, politics, and all sorts of other things. We were both historians who sort of wanted to be lawyers. I can remember feeling nervous and unprepared before having to present some of my work in seminar, my thesis project on two really big Supreme Court cases in the field of American Indian law. And believe me, I was stressed out. We would meet in his very Spartan office, and he always made really incisive eye contact when you were speaking to him. Bright, bright, blue eyes. He would listen very quietly, never interrupting. Very comfortable with silences. And then when you finished, spilling out your guts, coming up with all your excuses, telling him how you were not ready, he would pause for a few beats and then say: “You will never be prepared. You still got to do it.” He’d smile just a little bit as he said that. It was a tough lesson for some of his students, I think, but his point was that you can spend all your time worrying and fretting and fearing and preparing and not doing. Fear can keep you from doing what needs to be done, in public life, and in terms of what you want for your own lives. It is so easy to talk yourself out of pursuing your dreams, of tackling the challenges that may lie in front of you, and that lie in front of all of us.

Here’s what a student of mine wrote for her final essay in my Western Humanities course last year, a class that some of Plato’s characters might dismiss as mere stargazing. I gave the students an essay by a war correspondent reflecting on his long career and the seemingly limitless capacity of people for inhumanity and barbarism. I asked the students to write about human nature, justice, and the problem of evil, as they contemplated this article, and works by Sophocles, Plato, Thucydides, Augustine, More, the Bible, Shakespeare. “The question remains,” this very talented student wrote, “how do we account for all of the hatred, violence, and injustice that we witness? What words do we use to describe it? How can we possibly rationalize it and make sense of it? Where do we find its opposite in the world, and how do we eagerly point at that, so as to say, ‘See, this is also us. This is also me.’

“In a world and a human history overwhelmed by hatred, violence, and injustice, what counters it, I argue, is love, compassion, faith, and the courage to rise above it.”

There is great wisdom in these words.

Look for the beautiful more than the dutiful. Your rising generation is already better than mine in important ways—its open-mindedness, its tolerance, its acceptance of difference. I want to encourage your fearlessness, even where we have failed to demonstrate it ourselves. I know we have a lot of influence. Or at least we have the potential to be highly influential: a cruel or an uncaring word from us, for example, even when cast off thoughtlessly or uncritically, or because we are stressed out or too busy, can do so much damage, while a simple kind word, a single note of encouragement, can do something that students like you might remember for the rest of your lives, something that can help them write a beautiful life story.

I feel that I have the best job in the world. Each and every day, I have the opportunity, if I choose to truly be present, to truly listen, to be awed by your achievements, humbled by the obstacles you have overcome to get to and through my college, inspired by your creative thinking, pushed by your challenging questions, and amazed by the alacrity with which so many of you seek out injustice, attempt to correct oppression, and in thousands of small ways show the vital courage to make the world—our world—a better place. It saddens me that I will not be able to see you on graduation day, to wish you well, and most of all, to thank you for the past four years.