This past June a congressman from Washington state named Denny Heck introduced the “Remove the Stain Act,” which would rescind “each Medal of Honor awarded for acts at Wounded Knee Creek on December 29, 1890.” This may be old news for many of you, but I have wanted to write about the bill for some time. Deb Haaland and a Republican from California named Paul Cook co-introduced the measure, which was promptly referred to the Committee on Armed Services, where it currently sits. The fate of the bill is uncertain.

A friend who is active in the organization Veterans for Peace told me about the bill, which his organization supports. The Democratic presidential candidates Julian Castro, Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, John Delaney, and Marianne Williamson all have expressed their support. Each has joined in calling upon Congress to rescind the nation’s highest military honor from twenty cavalrymen who took part in the massacre at Wounded Knee.

Wounded Knee was one of those defining moments in the history of the American West, central to so many historians’ understandings of the Plains Wars and the place of native nations in the United States. Think back to Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, a flawed book which nonetheless influenced me greatly in my development as a historian, to the much more recent book by Heather Cox Richardson entitled simply Wounded Knee. Richardson’s book is well worth your time.

I tell the story of Wounded Knee in Native America. It is a story of native peoples searching for answers as they tried to adjust to life under the federal policy of concentration, and the brutal realities of the reservation system. Far out in the west, a Paiute shaman named Wovoka began to preach a message that combined Christian themes with nativist principles that answered their concerns. Wovoka, a messiah, had received visions, and he promised his followers peace if they lived honest lives and performed the Ghost Dance. He called for a return to ritual. The Ghost dance offered a way to restore balance to the world.

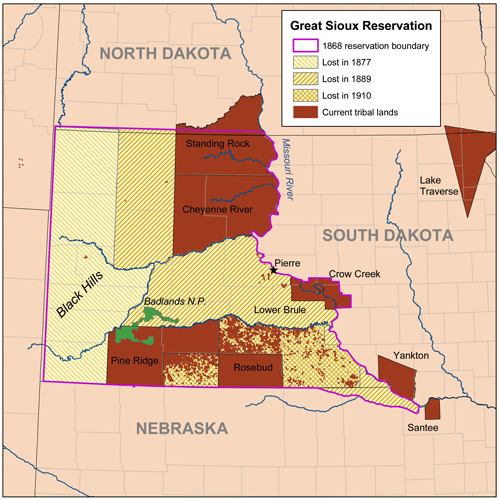

Word of the new religion spread rapidly. Native peoples sent emissaries to learn from Wovoka. Some rejected his teachings. Others found in them important truths, and as they adopted its central ritual, they transformed and altered elements of the original message. Lakotas, for instance, who returned from visiting Wovoka in March of 1890, taught that performing the Ghost Dance would bring back the buffalo and cause white people to disappear. The Lakotas had many grievances. Hunger constantly hounded reservation Indians. The government broke up the Great Sioux Reservation in 1889, reducing the lands held by the Lakota and severing the binds connecting communities together.

Sensing discontent, federal troops remained a heavy presence in Lakota country. The Lakota believers wore “Ghost Shirts” that some believed would stop bullets, and this made the federal authorities nervous. They worried that Sitting Bull, the great Lakota leader, would join the movement. When American authorities and the newly-constituted tribal police tried to prevent this, Sitting Bull resisted arrest. He and seven others died in a gunfight on 15 December 1890. It is hard to overestimate how crushing his death must have been.

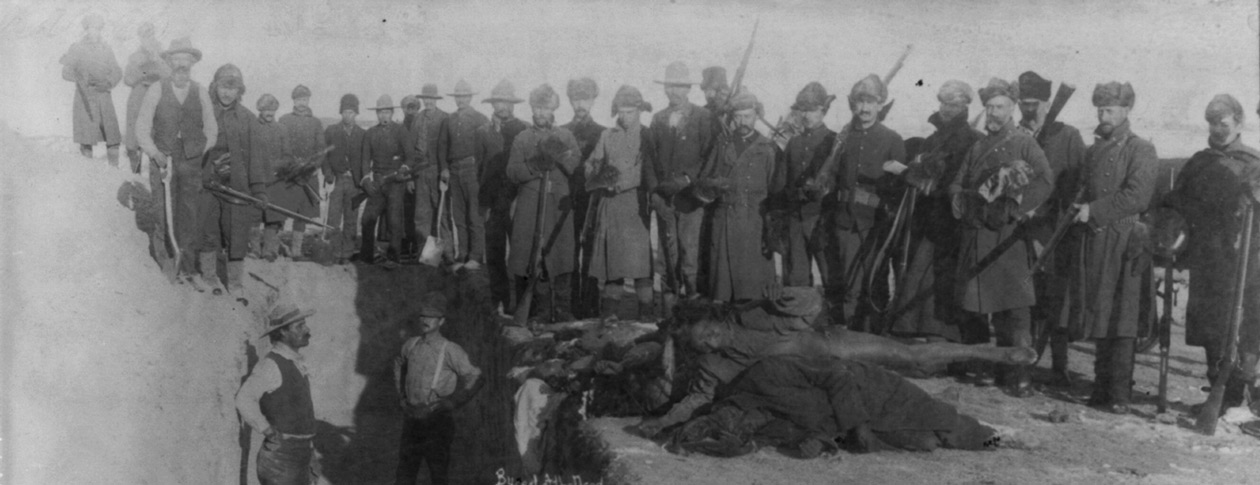

Another group of Ghost Dancers, led by Bigfoot, and consisting of many women and children, fled out onto South Dakota’s badlands. The government sent nine thousand troops to South Dakota, and five thousand of these to Pine Ridge. Fully a third of the United States Army, in its largest mobilization since the end of the Civil War, took up positions to suppress this peaceful protest. Federal troops surrounded them at Wounded Knee Creek in advance of moving them back to the Pine Ridge Agency. When the cavalrymen went to disarm Bigfoot’s followers, a shot was fired, perhaps accidentally, when a deaf young man refused to surrender his weapon. The federal troops opened up with rifles and artillery. 146 Indians died, including forty-four women and 18 children. It was the last military engagement between native peoples and American soldiers on the Plains, and the Wounded Knee massacre wiped out a religious movement among the Lakota Sioux that offered them hope for the future and a means for making sense of their life on reservations.

Charles Eastman, the newly-appointed doctor at the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota, learned of the massacre at Wounded Knee when the wounded started coming in. Most were women and children. “Many,” he wrote, “were frightfully torn by pieces of shell, and the suffering was terrible.” A blizzard blew in, and it took Eastman a couple of days before he could return to the battlefield. The first physician to arrive at that frozen and bloody ground, the experience affected Eastman deeply.

He saw the mangled bodies, and did what he could for the small number who had miraculously survived the federal artillery and gunfire. When he reached the site of Big Foot’s camp, he “saw the frozen bodies of men who had been in council and who were almost as helpless as the women and babes when the deadly fire began.” Eastman struggled to keep his composure. All about him he heard the “excitement and grief of my Indian companions, nearly every one of whom was crying aloud or singing his death song.” He found a few survivors, all babies. All were adopted by white people.

The massacre at Wounded Knee received condemnation at the time it occurred. Of the 350 or more native peoples who died, fully two-thirds were women and children. General Nelson A. Miles, he who ran down Chief Joseph’s followers just shy of the Canadian Line more than a decade before, wrote in 1891 that “I have never heard of a more brutal, cold-blooded massacre than that at Wounded Knee.”

When and if the “Remove the Stain” becomes law, the Medals of Honor will be rescinded, and the names of the twenty recipients will be removed from the Medal of Honor Roll. No family members will be required to return their ancestors’ medals to Congress, and the bill states that it “shall not be construed to deny any benefit from the federal government,” but its intent is clear. A symbolic act to be sure, passage of the bill will offer an important statement that in this instance Congress does not consider the slaughter of native peoples in any way to be meritorious, and that the stories told by the government about Wounded Knee are wrong.

It is worth talking about this bill in your classes, for it bears much in common with other, better known, efforts to revise American history. Activists have taken on Columbus Day and are replacing it with Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and they have commenced a powerful movement to remove racist commemorations of the Confederacy. They call for renaming buildings dedicated to slave owners and they are trying, I hear so often, to fix other places and spaces with names deemed offensive. The reaction of the right has been predictable. You heard it if you listened to the President’s speech before the United Nations General Assembly several weeks ago. He singled out academics who have launched an all-out assault on American values.

I think it is important to talk about all of this in our history classes. In places we have seen vandalism and destruction, but I would suggest that part of what we are seeing is a desire to fix a story that is broken, to revise and edit and set things right. What some might see as wanton destruction, others might see as an attempt to revise and reinterpret. It is raucous and rude, but it has provoked vital discussions.

Occasionally I will hear one public figure or another denounce “revisionist” history, or historians whose work they dismiss as “politically correct.” You can believe these people if you want to, but if that’s your choice, it is only with a poor understanding of what it is in fact that we historians do. Maybe we need to do a better job of explaining how we work to the public. We are the people, after all, who demand to see the evidence. We are the ones who relish the opportunity to hunt relentlessly for every scrap of relevant information. Never underestimate the tenacity of a historian determined to find what you might prefer to remain hidden. If we do not know where to look, we will figure it out, and we do not care what names you call us. We will debate you and insist on engaging you and we will make sure you understand that we are not in the business of repeating comforting myths or making you feel good about yourself. We look closely at the evidence. We keep receipts. Heck’s bill is a response to calls to set our stories right. It shows that many Americans believe that the time for an accounting is long past due.