I find the story of New York Congressman George Santos endlessly fascinating. Seven years ago, I wrote a biography of an Indian Confidence Man, a professional liar named Eleazer Williams. Like Williams, Santos fabricated his backstory. Both, in their quest for ascendance, denied who and what they were. Both were reviled for their deceptions. Nearly everything Santos has said about his background is a lie. And reporters, smelling blood in the water, continue to reveal on a daily basis new deceptions. It will only get worse for Santos. The most recent revelations are that he stole from a fund dedicated to providing medical treatment for a veteran’s canine companion. Given the utter emptiness of his resume, and the brazenness of his lies, it is stunning how far Santos’s deceptions have carried him. In Republican politics, I suspect he will go far.

How will historians tell the story of George Santos? He has done a remarkable job of avoiding reporters who will ask him challenging questions. His handlers will not respond to journalists’ queries. They neither return calls nor respond to emails. Like many politicians, he insulates himself from ever having to answer directly a person who challenges him.

We historians dig like badgers to unearth the primary sources we need to tell our stories. That is going to be hard enough as letters and documents become more rare, and as politicians communicate more and more through texts and emails that, it is reasonable to believe, many of us will never, ever see. The record will be thin no matter what. And what about the massive problem posed by the fabulist and inveterate liar? How do you tell the story of a person you are almost certain never has told the truth? These were questions I struggled with when I wrote about Eleazer Williams.

*****

Williams was an Indian confidence man. He was a liar and a teller of tales. There can be no denying this. Born at the Canadian Mohawk town of Kahnawake in 1788, he died in Hogansburg, New York, on another tract of Mohawk land, the St.Regis or Akwesasne reserve, seventy years later. He was a direct descendant of Eunice Williams, that unredeemed Puritan captive carried to Kahnawake from Deerfield, Massachusetts, as a child in 1704 by Mohawk raiders and their French allies. That is a fact. But he claimed to be other things at other times, and played and performed other roles during a long career. Some of them were true, others—not so much: A hero during the War of 1812, and commander of the “Corps of Observation” on the northern New York frontier, an Indian who fought on behalf of the United States in its second war for independence—all part of an elaborate and ultimately unsuccessful scheme to secure a pension for military record he could never corroborate; or the successful and admired Episcopalian catechist who against great odds brought Christianity to the so-called “Pagan Party” of the Oneidas in central New York, arguably the achievement he took the most pride in; or an expert on Indian affairs, a committed and early supporter of the policy known as “Indian removal,” and the leader of the relocation of the New York Indians to Green Bay.

There were other roles that Williams played, but he said less about these. He was a bad debt, dogged by creditors for sums both small and large for much of his life. He was a neglectful husband and absent father, who did little to care for his small family, and who effectively abandoned his wife and lone surviving son after losing all but a fragment of their lands in a botched real estate transaction in the 1840s. After his second child died in infancy, Williams disappeared. He had nothing to say to his wife.

These are significant faults, but they did not prevent Williams from holding great influence in discussions of the place and future on native peoples in the northeastern United States in the 1820s and 1830s. Williams was a professional Indian, advising officials in church and state on what ought to be done. He told them that their plans were sound, their hopes realistic, the support for their policies real, and he tried to make it so. This was how he made his living, put food on his plate, and a roof over his head.

Like all people, Eleazer Williams made choices about his identity, about how he presented himself to others. Like all people, as well, he confronted and contended with forces that in a variety of ways constrained and limited these choices. Williams could be different things to different people. Those who he met, and those who encouraged him or supported him or protected him or condemned him, carried expectations of who Eleazer Williams was and what he might do for them.

He thus played roles, and he served functions, some imposed upon him, some offered to him as opportunities, and others of his own choosing. It was a treacherous game. When he presented himself to the famous painter George Catlin in 1833, Williams still possessed a great deal of influence among powerful Americans interested in the conduct of Indian policy. He presented himself to Catlin in Wisconsin as a Christian and a clergyman, as a man comfortable both in Iroquois towns and at the centers of American power. Williams seemed quietly confident in Catlin’s portrait. He posed for Catlin wearing his ministerial attire, with his white lace collar standing out against his black coat and his dark skin. (Figure 1)

To understand Williams’s rapid rise to a position of such influence, where he was called upon by congressmen and senators, the governor of New York, a number of secretaries of war and presidents of the United States, it is important to look at his relationship with four entities, or four significant groups of people: the Episcopal Diocese of New York; the Oneida Indians in Central New York; Federal and state officials who as early as the Madison Administration were trying to concentrate or remove the Iroquois, of which the Oneidas were one of six parts; and lastly a well-connected business syndicate known as the Ogden Land Company.

First, there was the Episcopal diocese of New York, under the energetic leadership of its archbishop—and Williams’s great patron—John Henry Hobart. Williams had been born into a Catholic community at Kahnwake, but he was taken to southern New England as a child to receive his education from the descendants of his Puritan forebears in the Connecticut River Valley, Eunice Williams’s family. He spent a decade there before departing for New York City at the age of 21, where he met Hobart, became an Episcopalian—his third religion, in a sense– and began his career as a missionary. After a pair of false starts, he began preaching to the Oneidas in central New York.

He enjoyed great success at Oneida. The nation was divided over matters large and small. A significant portion of the Oneidas, hostile to the teachings of the Presbyterian missionary Samuel Kirkland who had been active in the region from the 1760s into the early 1800s, had not accepted Christianity and was known as the Oneida “Pagan Party.” In 1817, Williams successfully transformed the Pagan Party into the “Second Christian Party.” There is little doubt that he was a patient catechist and a captivating preacher. His influence grew, especially among those who thought Christianizing the Indians a laudable goal. His success as a missionary brought him considerable respect in religious circles. Williams, in the eyes of these white men, became a leader in the community. This presented him with challenges and with opportunities.

He was not the only leader in the Oneida community to be sure, but nobody else at Oneida wrote English as fluently or spoke the language with his facility. Thus when white people needed to speak to Oneidas they came to him before any Oneidas. And most of those white people wanted the Oneidas’ lands. Some were government officials from the state and the national government. Others came from the Ogden Land Company, a group of investors who had acquired a right of preemption to all the remaining Seneca lands in the western part of the state, which hoped along with government officials even this early to effect the removal of New York’s Indians to new homes somewhere in the west: the remote Allegany reservation in the far southwestern corner of New York State, or better yet, Arkansas, or Green Bay. Even the Archbishop John Henry Hobart encouraged the Oneidas to seek out a new home in the west. Their best friends wanted them to leave. Williams could not easily have opposed removal without losing the support of the man who underwrote his mission. Williams had resided in the Oneida country long enough to understand that there were other white men with whom the Oneidas might have to deal if they chose to ignore these men—the rustlers and the grog-sellers, the land sharps and the thieves who infested the margins of the Indian estate in New York. He was in a tough spot indeed. Removal often came to Indians as the least of a number of bad options.

So the man who came to Oneida to save Indian souls became a man who helped sell Indian lands. Williams explained in 1817 that though he initially opposed the idea of any “removal” of the New York Indians to the west, he came to believe that leaving the Oneida country ultimately was in the Indians’ best interest. He knew better than the converts to whom he preached, apparently. He told them that he wanted what was best for them, while telling the promoters of removal that support for their program existed even where it did not.

In 1818 Williams began “to broach cautiously among his Indian people a proposition of removing all the Indians” to new homes in “the neighborhood of Green Bay.” He was not alone in this. Other Indian leaders had reached the conclusion that native peoples might somehow outrun their problems by moving west. But Williams took his support a large step farther than other native advocates of removal. He was on the payroll of the Ogden Company. He signed deeds and receipts on behalf of the Mohawks at Akwesasne, even though they had not authorized him and he was paid by interested parties to do so. Federal authorities paid for Williams’s travel between New York and the capital and Green Bay. He established close connections with those white men, who for reasons that had little to do with what was best for native peoples, hoped to relocate New York’s Indians and exploit their former lands. This was how he made his living. These facts complicate Williams’s claim that he came to removal reluctantly, that he would have preferred to stay in New York if the Oneidas and their native neighbors could find some meaningful protection of their rights to person and property. Williams, like all who dance with the devil, found that many Oneidas opposed his efforts, and began to question his motives.

He persisted. He led a small number of Oneidas to Wisconsin. Others, as the Oneida estate dwindled around them, felt they had no choice but to follow. He helped to negotiate the treaties that purchased from the Menominees and Winnebagos of Wisconsin a homeland for the Oneidas. He preached on occasion. He seems to have helped out where he could, but the Oneidas had surprisingly little to do with him. He spent most of his time with the US garrison. But when he posed for this picture by Catlin, he still held great influence with church officials, with government agents interested in removal, and with the Ogden Company. He was their Indian man. But that influence would not endure. The year after he sat for Catlin the tales he told caught up with him. The Oneidas with whom he had traveled to Wisconsin and those who remained behind in New York deemed him unwelcome and let officials in the state and federal governments know that. In response to Oneida complaints, the Episcopal Diocese of New York recalled him, effectively ending his career among them as a missionary. He was useless to the church if his flock did not want him around. The Ogden land Company, which had paid Williams to help persuade more New York Indians to move west, cut him loose as well. The Company felt that Williams had done about all he could for them, and they no longer were willing to throw money at the man they had hoped might help them relocate the New York Indians. Many of the Oneidas had moved west, but the rest of the New York Iroquois, and especially the Senecas, remained committed to their New York homelands. Where Williams led, the Ogden Company’s leaders now believed, few Iroquois followed.

He spent the years following living the “life of a misanthrope,” one of his most hostile biographers wrote, “spending but little of his time at Green Bay, but mostly traveling up and down the lakes, and between Buffalo and the Atlantic states and cities.” He did so on borrowed money, or on ill-gotten gains. He lived a life of disarticulation, divorced from any community, an acquaintance of many but a friend of few. Williams scraped by, but it was a rough decade and a half, filled with personal and financial setbacks. Desperate for an income, Williams re-invented himself in the 1840s. He assumed a new role, and played a new part. He invented a character. He developed an elaborate backstory. And, as he requested contributions for a mission he never established, he played his role. He was now no longer an Indian at all, he claimed.

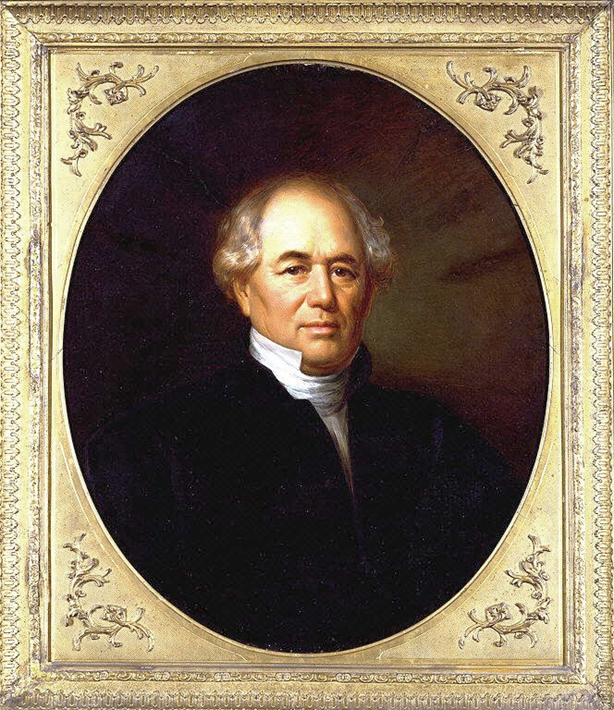

He was the Dauphin, the lost, star-crossed child of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, who had been squirreled out of France by Royalist supporters and raised in secret amongst the Iroquois along the St. Lawrence. That is what he said. His fame—or his notoriety—growing, he sat for a portrait by Giuseppe Fagnani, an artist who had lived in Europe “in intimate acquaintance with the families of the Sicilian and Spanish Bourbons,” and a man known in America as “the portraitist of crowned heads and statesmen.”

Williams of course could not persuade everyone that he was the son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and for good reason, but he convinced Fagnani. The “general Bourbonic outline” of Williams’s face and head impressed Fagnani, as did several other “physiognomical details which rendered the resemblance to the family more striking.” The “upper part of his face,” Fagnani wrote, “is decidedly of a Bourbon cast, while the mouth and lower part resemble the House of Hapsburg.” Fagnani depicted a man with skin lighter than that shown by Catlin, with hazel eyes and light colored hair that had turned grey. Williams, Fagnani believed, could well be the dauphin because he demonstrated so many of the physical markers of “the Bourbon Race.” (Figure 2)

This is the story that Williams told. François-Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Marie d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville, a member of the French royal family, left Buffalo on 13 October 1841 aboard the steamboat Columbus bound for Green Bay. According to Williams, Joinville sought him out. Joinville told Williams that the son of Louis XVI, to avoid the terrible fate that befell his parents during the French Revolution, had been secretly carried across the Atlantic by Royalist sympathizers and deposited among the Iroquois in Canada. Thereafter he disappeared, and had not been heard from since. Sizing up Williams, Joinville believed that at long last he had found the Dauphin.

Williams claimed that this startling news left him devastated, that “it filled my inward soul with poignant grief and sorrow.” He continued,

Is it so? Is it true, that I am among the number who are thus destined to such degradation? From palace to a prison and dungeon–to be exiled from one of the finest empires in Europe and to be a wanderer in the wilds of America–from the society of the most polite and accomplished countries to be associate with the ignorant and degraded Indians?

If it was God’s will that Williams be cast from his seat at Versailles to live with savages, Joinville had something very different in mind. After finding the Dauphin at long last, he wanted Williams to disappear once again, but only after he signed a document formally abdicating any claims to the throne of France. Williams, with a dramatic flourish, refused. Oddly, he failed to keep the copy of this document.

The Joinville story was little more than a fiction embossed upon a chance meeting between the two men. It was not true, but that did not keep Williams from telling the story. He began to do so in 1848, after the death of his “reputed father,” and in 1853 the story took off, when the Reverend John Holloway Hanson published an essay in Putnam’s entitled “Have We a Bourbon Among Us.” A book followed the next year. Hanson produced a list of more than two dozen “facts” that he felt helped make his case that Williams and the Dauphin were one. Hanson told the stories of Joinville and other French émigrés who believed that the Dauphin had been secreted out of France and carried to America. Hanson pointed out that Williams’s name did not appear in the baptismal register at Kahnawake, suggesting that his actual birthplace was someplace else…..like France. Hanson said that Williams had in his possession an ornate gown that once had belonged to Marie Antoinette and that he carried with him, as well, “the varied marks on his body”– scars on his knees, and scars on his face–that “correspond exactly with those known to have been on the body of the Dauphin.”

Hanson asserted as well that Williams’s “reputed mother” did not acknowledge him to be her child,” that Williams closely resembled Louis XVIII, and “that he has none of the characteristics of an Indian.” Hanson, moreover, repeated a story often recited by Williams’s observers, one that gives us a sense of how Williams played the dauphin. One night an elderly man was showing to Williams a collection of engravings and lithographs of characters from the Revolution. Williams leafed through the collection, but at the sight of one, he seemed disoriented, confused, frightened all at once. He staggered backward, said something to the effect of “God God…That face….It haunts me still,” and then asked to be excused and staggered from the room. The guests ran to the book, looked at the engraving. It was Simon, the sadistic tormentor of the imprisoned Dauphin.

Hanson attempted to make his case. He believed that the evidence he presented showed “1st. That Louis XVII did not die in 1795.” Second, that a cabal of French royalists secretly carried the Dauphin to America and to a spot near where Eleazer Williams grew up. Hanson believed that the evidence showed clearly that Williams was not an Indian and, therefore, “that Mr. Williams is Louis XVII.” Hanson, according to the New York Times, asserted that his evidence was “irresistible,” and he said he stood willing to stake “his reputation as a man of common sense and common discernment on the issue.”[i]

A number of critics were willing to take that bet. Putnam’s, one pointed out, frequently published sensational stories, though few of them seemed as absurd as Hanson’s. Williams, another pointed out, was several years too young to be the Dauphin and, besides, his mother, who certainly ought to have known, gave a deposition in which she stated that Eleazer Williams was her fourth child. A critic in the Christian Enquirer pointed out how “Mr. Williams has been very unfortunate in losing all the documents on which his story is grounded.”

Now here is where the debate began to turn. Hanson responded to his critics not so much with documents, but with “scientific” evidence, at least as it stood at the time. Hanson took Williams for examination by an impartial panel of medical experts in New York City. One physician concluded that Williams had “a lofty aspect, strongly marked outline of figure, obviously European complexion.” Another found that

the physical development of Mr. Eleazer Williams is that of a robust European, accustomed to exercise, exposure to open air, and indicative of the benefit of a generous diet, and a healthy state of the digestive organs. He might readily be pronounced of French blood. His general appearance and bearing are of a superior order; his countenance in repose is calm and benignant; his eyes hazel, expressive and brilliant, and his whole contour, when animated, indicates a sensitive and improvable organization . . . There are no traces of the aboriginal or Indian in him.

Eleazer Williams took advantage of the fame. He spoke frequently, and found more pulpits open to him, and larger audiences willing to listen to him than ever before. He used his notoriety to raise money to support himself and his missionary enterprise, to pay for the construction of a church that would never be built, a mission that would never be constructed. He collected as much as sixty dollars in one night. Skeptics, intent on exposing “the ridiculous humbug lately published by Putnam,” attended his talks. But the faithful and the curious came out to see the Dauphin on tour as well. They responded with enthusiasm, according to most accounts, to Williams’s call for donations. Indeed, Williams reported to one of his old antagonists, that “my appeal to the churches in your Atlantic cities has been responded well to my satisfaction.” Williams, it seems, was making a living as the Dauphin.

He preached all over. Troy and Albany in New York. In the Conneticut River Valley towns. He spoke in Hoboken, and in Brooklyn. He preached in Washington, DC. In March of 1854 he preached at churches in Baltimore, sometimes three times a day. At each, large audiences gathered to hear him speak “of his mission among the Indians, and the words he uttered fell from his lips with increased effect from the convictions many had that the representative of a long line of French kings spoke to them.” He made short trips that spring to New York City, and to Camden, New Jersey, but he spent most of his time in Philadelphia where according to one newspaper he preached at nearly every church in the city. At each stop, he spoke about the condition of the Indians, “and the duty which the American people owe to the Aboriginals of the land.” Williams raised “a handsome amount towards the object of ameliorating the condition of the red men of the forest,” while creating “a profound sensation in the minds of those who have investigated the facts in relation to his own most remarkable history.”

Many of those who attended his presentations and dropped their coins in the collection plate were drawn in more by Williams’s claim to be the dauphin than by a desire to support missionary activity among the Mohawks at Akwesasne.

Some in those audiences found the notion that Williams was the Dauphin entirely unbelievable. But they did not base their skepticism on the obvious problems with the story. Instead, they focused on a variety of “racial” characteristics that to them seemed to demonstrate that Williams was an Indian or, at best, a “half-breed,” both of which of course disqualified any claim that he might be the Dauphin.

Williams engaged in his performance at the tail end of a period where science had come to define native peoples of the “American Race” as inferior to “Caucasians.” Charles Caldwell, for instance, one of the most important of these scientists of race, after examining the heads of members of an Indian delegation visiting Washington, D.C., asserted that the “native bent” of white people led them towards civilization, while with Indians, the reverse was true. “Savagism, a roaming life, and a home in the forest, are as natural to them, and as essential to their existence, as to the buffalo or the bear. Civilization is destined to exterminate them in common with the wild animals among which they have lived, and on which they have subsisted.” The only hope for their survival, Caldwell thought, was cross-breeding with white people.

These pseudo-scientific inquiries led rather mechanically to lists of characteristics that defined the different races. Often these were little more than stereotypes, and they could not account with much ease for those native people who had managed to “improve,” but those interested in this science acted on its assumptions. Samuel George Morton, so enthusiastic a collector of human skulls that his friends jokingly called his Philadelphia study an “American Golgotha,” believed that in their measurement lay the key to understanding racial difference. He cleaned the skulls, coated them with varnish, measured their angles, and their volume by filling the cranium with pepper seed or buckshot or liquid mercury.

From his studies, Morton deduced the intellectual and physical inferiority of American Indians relative to Caucasians. If Caucasians, for instance, possessed “naturally fair skin,” hair that was “fine, long and curling and of various colors,” with a skull “large and oval” and a face “small in proportion to the head, of an oval form, with well-proportioned features,” a “brown complexion, long, black, lank hair, and deficient beard” marked “the American race.” In Indians, Morton wrote, “the cheek bones are large and prominent, and incline rapidly toward the lower jaw, giving the face an angular conformation.” The Indians’ “upper jaw is often elongated and much inclined outwards, but the teeth are for the most part vertical. The lower jaw is broad and ponderous, and truncated in front.” The teeth are also very large, and seldom decayed,” Morton continued, “for among the many that remain in the skulls in my possession, very few present any marks of disease, although they are often much worn down by attrition in the mastication of hard substances.” Their hair was always straight and black, and among the Indians, “no trace of the frizzled locks of the Polynesian, or the wooly texture of the negro, has ever been observed.”

Morton could read the skulls and deduce more than mere physical characteristics. “The bold physical development of the American savage,” he wrote, “is accompanied by a corresponding acuteness in the organs of sense.” Indians were “vigilant,” a product of “the constant state of suspicion and alarm in which the Indian lives.” They spoke “in a slow and studied manner, and to avoid committing himself he often resorts to metaphorical phrases which have no precise meaning.” They employed subterfuge against their enemies, who they pursued relentlessly. The Iroquois especially, Morton said, “possessed all the other Indian characteristics in strong relief.” They “paid little respect to old age; they were not much affected by the passion of love, and singularly regardless of the connubial obligations; and they unhesitatingly resorted to suicide as a remedy for domestic or other evils.” The Iroquois, he said, “were proud, audacious, and vindictive, untiring in the pursuit of the enemy, and remorseless in the gratification of their revenge.”

Morton died in 1851, but the ideas he and his cohort of fellow race scientists advanced provided a vocabulary and a widely disseminated and understood set of conceptual categories. Few doubted “the intellectual and moral superiority over all other races of men” of white Americans, and they knew that differences in physical traits could determine racial difference. Williams confronted these conceptual categories when he presented himself to audiences as the Dauphin.

His critics thus dismissed his claims not on the basis of their implausibility, or because they thought that Williams was deluded or insane or nuts, but because in racial terms, he did not seem to evidence any of the characteristics they associated with noble European birth. The author of a piece that appeared in the New York Herald, for instance, who claimed to have met Williams several years before, argued that “no man acquainted with our aboriginal race, and who has seen Mr. Williams, can for a moment doubt his descent from that stock.” Of Williams, he wrote, “his color, his features, and the conformation of his face, testify to his origin. He looked like a “half-blood Indian,” and not at all like a Bourbon. A. G. Ellis, who had known him since the 1820s, said that Williams was “unquestionably a half-breed Mohawk Indian, having all the distinctive features of the race: the black straight hair, the black eyes, the copper color and high cheek bone; and all who knew him when young remarked this.” Years later, Ellis described Williams as “dark enough for ¾ Indian,” and he clearly believed that color did not lie. C. C. Trowbridge, who knew Williams in Wisconsin, laughed at the Dauphin story. Williams “had all the peculiarities of a half-breed Indian, as undoubtedly he was . . .If he had been otherwise, mentally or morally, his hair and complexion would have stamped him as of mixed savage and civilized blood.”

Science came readily to the assistance of those who doubted Williams’s clams to be the Dauphin. Peter A. Browne, for instance, a race expert in Philadelphia who could “ascertain the race of an individual by the hair upon his head, with as inevitable certainty as a phrenologist can determine character by bumps,” concluded from his examination of Williams that “there is a difference in the diameter of the hairs of Mr. Williams,” and that “some are oval, some cylindrical,” and that “therefore he is a cross of Indian and white” and “consequently he is not the Dauphin.”

And so it went. Williams had his supporters, and they trotted out race science as well. One New York reporter found that Williams did not look like an Indian and that with him, “the forehead and the lower part of the face show a great analogy to certain physiognomies of” the Bourbons. Another New Yorker reported that although Williams’s complexion was “rather dark,” having “become somewhat bronzed by exposure,” his features were “heavily moulded, with the full Austrian lip, eyes dark hazle, and hair, dark, fine, and curling, somewhat sprinkled with gray.” A correspondent from a Troy, New York, newspaper concluded that in Williams’s features “we could trace no works of the Indian. They are decidedly European.”

While in Philadelphia in the spring of 1854, Williams subjected himself to medical examination once again. The doctors—this time from the Pennsylvania College of Physicians, the Jefferson Medical College, and the United States Navy—found that Williams possessed scars consistent with those received by the Dauphin, as Hanson had claimed. Further, they found that

his skin, where it has not been exposed to the weather, is that of a pure white man. His hair is of a silken fineness and curls freely. his hands and feet, his wrists and ankles are very small, indicating an ancestry unaccustomed to any hard use of their bodily organs. His countenance and reception are peculiarly benign and gracious–totally free form the reserve and austerity of the Indians.

This was another point that some of Williams’s audiences raised. Not only did he look like a European and unlike an Indian, but he did not act in ways that Indians were believed to act. In Williams’s “mental likeness,” one newspaper reported, “there is something closely allied to the best Bourbon traits,” though the paper gave its readers no sense of what those traits were. In Camden, New Jersey, Williams impressed the group who had gathered to meet with him after his missionary appeal. “Much to our surprise,” one observer wrote, “we found him easy in manners, free and agreeable in conversation, with the polished bearing of a gentleman accustomed to refined and cultivated society.”

As Williams traveled through the Northeast, preaching in several cities, newspapers reported on his progress. Church-goers and the curious assembled to hear him speak. Many of them asked themselves the same question: was he or wasn’t he? Was Eleazer Williams the son of the King of France or an Indian from the Northern wilds? Was he white or red, civilized or savage? As those in the audience contemplated these questions, they looked closely at Williams. They watched his behavior, studied his comportment. They measured his color, his features, his hair, against what they believed to be the identifiers of “white” and “red.” They considered and calculated the fraction of Indian blood that flowed through his veins. But still, he seemed to be losing this one, and though interest in the Dauphin was strong, Williams began to look elsewhere for a livelihood, trying to extract money from the government for a range of alleged and unmet obligations

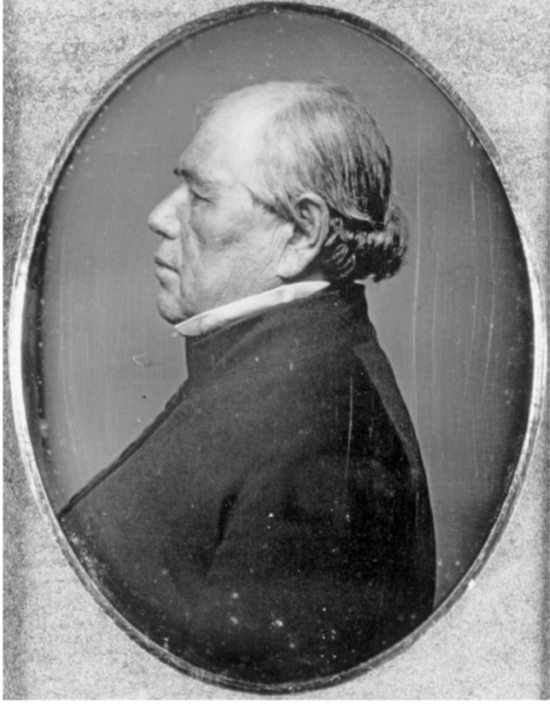

Williams traveled frequently and spoke often as the Dauphin. His journeys took him back through Longmeadow, Massachusetts, where he spent his adolescence receiving an education in Calvinism from the descendants of his Puritan forebears, and nearby Springfield. He returned, now four decades later, not as the descendant of Eunice Williams, but as the son of a French king and his queen. He sat for a daguerreotype in Springfield. He might have faced the camera. That was, after all, the purpose of the daguerreotype, to reveal the subject’s true likeness. (Figure 3)

But the man who captured Williams’s image in his Springfield studio evidently had something else in mind. He took a profile, a side view, with the light coming from above. The image highlighted Williams’s “Indian” features, his high cheekbones, for instance. Poses such as this were relatively rare. The image, in this sense, constituted a racialist text, a commentary on Williams’s chosen identity as the dauphin. Williams could not possibly be the dauphin, his critics pointed out, because he possessed the racial features they associated with American Indians. Williams’s ability to define who he was, in this sense, ran into assumptions strengthened by the emerging American science of racial difference. And Williams, according to that standard, simply could not measure up.

We who write history try to understand the people about whom we write, to see the world as they saw it. We dig through the records, asking questions, searching for insights, and asking more questions. We take a crack at leaving a final word, and a fitting assessment. Excavating the documents necessary to tell the story of an individual’s life can be difficult enough, as we sift the knowable from what is unknowable, as we determine what is plausible, what is impossible, and what makes for a persuasive educated guess. We can tell where Williams went, with whom he met, and other things that he did. But this information, these data, can only take us so far. We are more than what we do, and the people we write about are the sum of all the stories they feel compelled to tell about themselves or that others might feel driven to tell about them. These tales—stories of creation, and stories of vindication, self-discovery, denial, deception and defeat—are the matter historians must shape and examine as they work not only to understand a life, but to fit that life in a meaningful way into some broader context. When the subject of the study is a liar, the task obviously becomes much more difficult.

The liar Williams I believe told his tales to play for sympathy and to craft his own image, but most of all, it seems, to make ends meet. He did not tell lies primarily to defend a community or to promote a grand cause, although one might claim that in a quixotic way he tried. He lied when it was convenient and useful for him to do so to pursue what he thought was in his best interest, or to advocate or support a policy he thought right and correct. And he lied to place food on his table and a roof over his head. It was not easy for a native person living in white America to earn an honest living, and Williams told many of his tales to keep the support of his patrons in church and state. Lying, in a sense, became Williams’s occupation. Some of these lies he told clearly with the intent to deceive. Some of his tales involved exaggeration, or evasion, or puffery. We can see, if we look, evidence that Williams used gestures, and behaviors, and silence, to convince those with whom he interacted that what was false actually was true. Williams told many tales at many points in his life: that those who worshiped with him wanted to leave their homes; that he was a hero whose efforts on the field of battle received no reward or that he was the Dauphin .

He chose to lie. It is important to remember that. Resourceful native people, a number of historians have pointed out, eked out their livings in communities that rested uneasily on the margins of white America, encircled or pressed upon by settlers and the citizens of the republic who felt little respect or appreciation for Indians as Indians. When traditional economies collapsed, native peoples adapted their old skills to new economic realities. They hunted and fished and trapped where they could. They raised livestock and grew crops. They learned trades and sold their wares. But these remained communities on the edge.

But Williams maintained few ties to the native communities in which he lived and worked. Always highly mobile, traveling by canal boat and steamboat and rail, place meant little to him. Connections to kin in the end seem to have mattered not at all. He was a man apart. He worked with the church and the state and put those interests, and his own, ahead of the native communities he claimed to serve. And as he did so, never in one place for long, exploiting the opportunities the Antebellum republic provided him for finding an audience, he performed—as soldier, broker, missionary, and king, testing and running up against the boundaries and categories that at different times and in different ways defined who he was and the limits of what he might become.

*****

I suspect that George Santos knows well the difference between truth and lies. He lives in a world that makes invention easy. He has, to a greater degree than the rest of us, curated a self-image. He has consistently appeared before audiences that accepted him because he shared values they held so deeply that nothing else mattered. He will soon begin playing the victim, another role he will accept consciously and clearly, because it will help him pursue his interests.

The Republican party in Washington understands the type of person George Santos is. They simply do not care, because he will vote the way they want him to vote on the issues Republicans care about most. Like Williams, Santos has mastered the art of telling powerful people what they want or need to hear. I suspect that he is, like Williams, a compelling teller of tales. Like Williams, I suspect that Santos is hard-wired to detect both those who are gullible enough to believe his lies and those who in power who see through his stories but just do not care. In this sense, I suspect he is as adept at kissing ass as he is at telling lies. If New Yorkers do not get to him first, he can probably expect to have a long career in national politics, so long as he convinces those he serves of his enduring utility.

Thank you for a very revealing essay on Santos and Williams.

January 18, 2023 at the World Economic Forum at Davos Switzerland Fawn Sharp president of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) spoke for Indigenous Peoples on Environmental Issues. She invoked words that Chief Seattle was supposed to have spoken. Her speech is available to hear on line. And I watched and listened to her on the WEF site.

This speech of Chief Seattle was really written in 1972 by Ted Perry for a film on Home. The myth of this powerfully written environmental speech continues. My former husband Jim Thomas was PR director for the NCAI 1970-71 in DC. So I am so puzzled that Fawn Sharp used words that all of us who write on Indigenous Issues, know they were not Chief Seattle’s thoughts and words.

There’s plenty on the internet for people to research on their own. Don’t take my word for it. Check it out yourself.

Indigenous Peoples need to be at the forefront of Truth. Especially on environmental issues. It’s call, the Little Green Lie. A title the Reader’s Digest put on the essay they ran many years ago. I still have my original copy.

Annie Olson

Thanks for this Annie. I always value your feedback.

Theresa lot I could share with you about the Godfather premiere and going to the apology event for Littlefeather in september