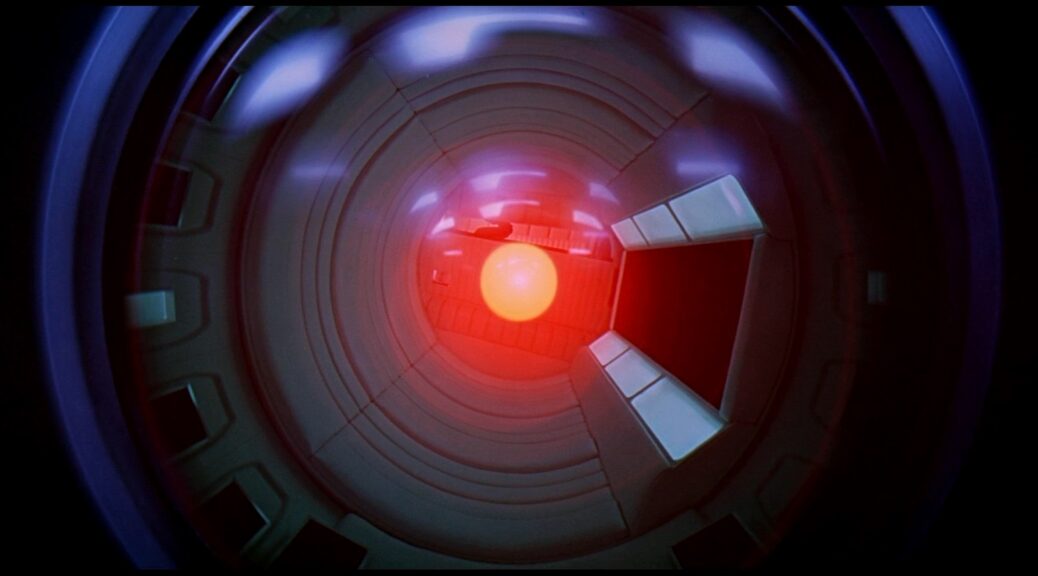

“The 9000 series is the most reliable computer ever made. No 9000 computer has ever made a mistake or distorted information. We are all, by any practical definition of the words, foolproof and incapable of error.”

I do not think we need to freak out about Chat GPT, not yet anyways. I write these words as one who can not explain how this particular artificial intelligence system operates. I also do so as a teacher who long has been critical of those of my historian sisters and brothers who give to their students the same rote assignments year after year. If you are one of those unimaginative teachers, well, you may in fact be toast. A student who uses Chat GPT to respond to an essay prompt asking her to explain the meaning of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” for instance, will be able to produce a very nice essay that I expect will easily surpass your very low standards.

I have been reading about Chat GPT for the past several weeks. I listened to an hour-long radio show on the local NPR affiliate that explored the question of how menacing this technology might be for educators. I understand that experts in information technology who know more about these systems than I ever will are deeply concerned. So let me tell you where I am coming from, so you can decide if you want to read any further.

The vast, vast, majority of students, I believe, are honest. The vast majority of students want to have a positive experience in the classroom. They want to learn, even in those classes they are compelled to take to fulfill a requirement that may have nothing to do with their major. I believe, as well, that the small number of students who cheat do so when they are bored and uninspired, because they lack confidence in their ability to do the coursework well, or because they are so stressed out that they do something dumb out of desperation. In each of these instances, I believe, the instructor bears some significant responsibility for the student’s cheating:

- she or he failed to engage the students, to convince them that the subject he or she taught was worth learning about and that the students had thoughts and ideas worth sharing, even when the work was extremely challenging;

- she or he failed to convince the students that they had the ability to do the assigned work, whatever self-doubts that student felt, or to offer the student the sort of assistance needed to successfully complete the assignment;

- or because she or he failed to pick up the vibes in the room, which are not at all difficult to discern for instructors who teach with their eyes, ears, and hearts open.

So I played around with Chat GPT. I understand that the technology learns and improves over time. That may be so. I fed into the system three different assignments that students in my classes might complete. In the first, I asked it to write a short reaction to the Supreme Court case of Oliphant v. Suquamish (1978). This is a topic students enrolled in my Indigenous Law and Public Policy course might choose for their journals. I next asked Chat GPT to write an essay explaining the disappearance of the Lost Colonists at Roanoke, a topic about which I have some strong feelings that you can read about in The Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand. Finally, I asked it to write an essay on the historical significance of the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua, the subject of a book I published in 2015.

Chat GPT produced answers that were competently written. The grammar, word use, sentence structure, and paragraph coherence all are better than what many of my students are capable of producing. I suspect that the gap between a student’s conversational and written English would be readily apparent as a “tell” that a student has used an AI program, just as it is for older, more low-tech, types of plagiarism.

The entry for Oliphant was factually correct and covered most of the major points in the case. But it was also devoid of analysis and so absent of feeling about this destructive case that the essay felt flat. It did not quote the decision, nor did it provide any citations.

I felt the same way about the essay on the fate of the Lost Colonists. One possible explanation is this, the essay reads. Another explanation is that. A third explanation posits something different, and yet another says something else entirely. Each of the four explanation has been advanced by a scholar. Each of the explanation is plausible. What Chat GPT failed to do, however, was provide compelling analysis and argument. There is no stewing over difficult documents here, or wrestling with ambiguous evidence. When I make assignments, I do not ask students to come up with a list of likely explanations derived from secondary sources. If you are like me, you ask them to wade into the documents, to ask questions, and offer an explanation supported by primary sources. Good historians will quote those sources as they attempt to make their case successfully. We make arguments, not lists. We also expect students to cite fully and frequently. Chat GPT does none of these things.

The essay on Canandaigua was surprisingly bad. Significant factual errors occurred. Redundant paragraphs made the same point over and over with slightly different wording. No quotes from primary sources, and no citations were present. A student using Chat GPT to write a historical research paper will be caught by all but the most inattentive instructor.

Perhaps I am too sanguine. Chat GPT, as I understand it, will learn and become more proficient. Perhaps students will use it as a crutch, as an outline generator, to which they will add bits and pieces of appropriate material to allow the papers they generate to look and sound like student work connected to a specific classroom context. There is nothing to stop a student from throwing in a couple of quotes from other readings to give the paper a veneer of having been researched. All of these things could happen. If you ask students to do work in stages, to submit outlines and drafts, I still expect that you will make it very difficult for students to use Chat GPT.

Look, I find what I teach very interesting. I like to share it with students. I am interested in all sorts of questions about the past. If I cannot inspire my students to take an interest in the subjects that I am teaching and that I have devoted much of my life to studying, or if I fail to convince them that it is important, that is my failure alone. I am failing as a teacher. Almost all students–and I truly believe this–want to learn. They want to be turned on by an idea. They want to benefit from the classes they take. Even the quietest student in class has something of value to say.

Please, teachers, do not look at your students as potential cheats who you must constantly surveil. Will some students attempt to cheat? Will some of them engage in plagiarism? Yes, I suppose some might, if you let them. Good teachers, who are interested in their students, who engage with them in the process of learning, and convince them of the importance of what they teach, have little to worry about.