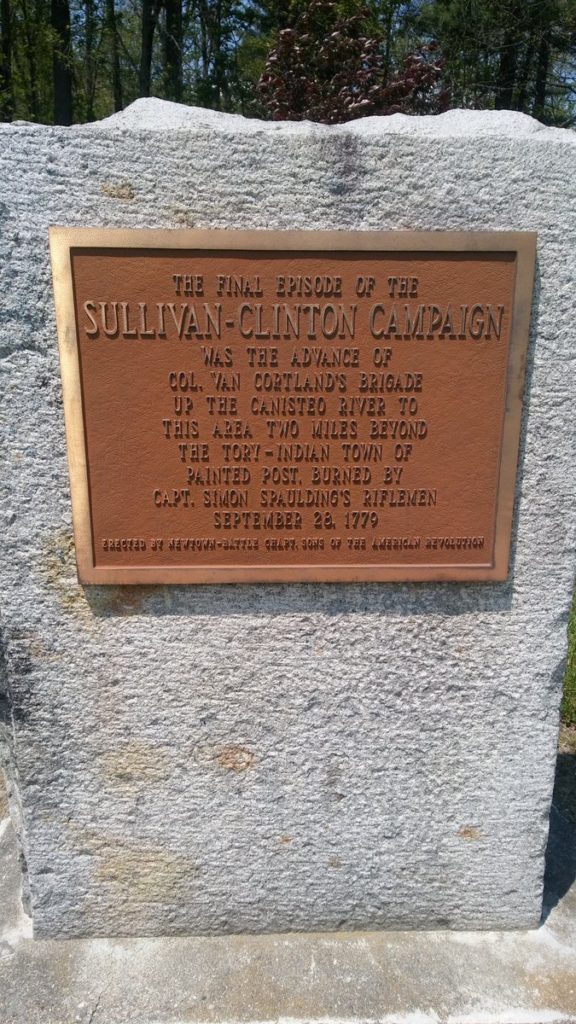

Driving from Rochester to Washington a couple of weeks ago, I saw this historical marker on Route 15, just north of the Pennsylvania state line. It commemorated the “final episode” of the Sullivan-Clinton campaign in 1779. American forces invaded the western Iroquois homelands and burned towns throughout the “Finger Lakes” region of western New York. I tell the story of the Sullivan-Clinton campaign in Native America. I have also written about it on this blog here and here. Because I cross the paths Sullivan’s army traveled frequently, I am familiar with many of the historical markers identifying key sites in the campaign.

But his one was new to me. The people who wrote it believed that the Sullivan-Clinton campaign ended near this spot. The soldiers completed their mission. The story began, and it ended.

I find myself these days spending a lot of time talking history with what some might call “amateurs”–people who are interested in the past, who enjoy reading history, even if they do not study it systematically. One of the things that strikes me about these conversations is that we have not been as effective as we might have been in describing what it is that we do, and why we do it. We have not, among other things, explained how much choice is involved in the historical enterprise. We choose the stories that we want to tell. We determine what questions we want to answer, how we can best answer them, and how best to present the results of our research. We determine the scope of our work geographically–how much space we are going to cover, and chronologically. He have to decide where in time our stories begin and end.

According to this marker, the story of the Sullivan Campaign, ended “with the advance of Col. Van Cortland’s brigade up the Canisteo River to this area two miles beyond the Tory-Indian town of Painted Post burned by Capt. Simon Spaulding’s riflemen, September 28, 1779.” Joseph Fischer, in the most thoroughly-researched military history of the invasion, says it began in July and ended in September.

But did it?

The soldiers went home. Or they went to fight elsewhere. Some of them later returned to New York, settling on lands seized from the Iroquois. But the expedition was, as Fischer calls it, a “well-executed failure.” That apt title implies that despite the invasion, the Indians remained. They resisted. Their towns burned, the fields destroyed, the orchards cut down, they settled at the refugee haven around British-controlled Fort Niagara, or along Buffalo Creek. They suffered through a brutal winter. They fought on. And when the British abandoned them, they faced the onslaught of settlement encouraged by private land companies, the state, and the United States. They signed treaties and formal deeds of cession. New York’s rise as the “Empire State” could not have occurred without Iroquois dispossession.

But after the campaign the Senecas remained in New York. That much is obvious. They resisted their complete dispossession. They obtained security for some of their lands at Canandaigua in 1794, sold much of their homeland in 1797, and in 1802, 1815, 1826 and 1838 as well. But they are force still in western New York. Their gaming enterprises in Niagara Falls, Salamanca, and Buffalo are significant. They have survived, even though they continue to contend with the obtrusive power of the state. Perhaps the story of the Sullivan-Clinton campaign, which its planners hoped would lead to “civilization or death” to the American “savages,” has yet to end.

History is what it is. History is written by the victorius. A more accurate accesment can be made by examining the writings of the period and the various perspectives of the participants. But the most important historical perspective is motive., Motive takes no side. The primary motive of the Iroquois to ally with the British was to defeat the Adirondack Indians (an Algonquin Indian tribe.) There were many wars between these tribes. Iroquois farmed. Algonquins didnt. They were hunter/gatherers…..who had a habit of raiding Iroquois villages at harvest time. This is what primarily led to the Iroquois Confederacy. Adirondack means bark eater….an Iroquois insult . Iroquois is a French boggled version of an Adirondack insult. Now we begin to see man’s inhumanity to man….It’s a universal constant……wherever there are at least 2 men. There are no,” pure as the driven snow ” motives among men. Indians were slaughtering each other before europeans (who had been slaughtering each other for centuries.)arrived and began slaughtering them…..Taking a break as colonists ,to slaughter the French then the British. Then again as the North and the South, before returning to the slaughter of Native Americans in earnest. And you ask…”Did it end there?”…..Of course not . Seriously…..How much history……and human sacrifice can be placed on one roadside historical marker?