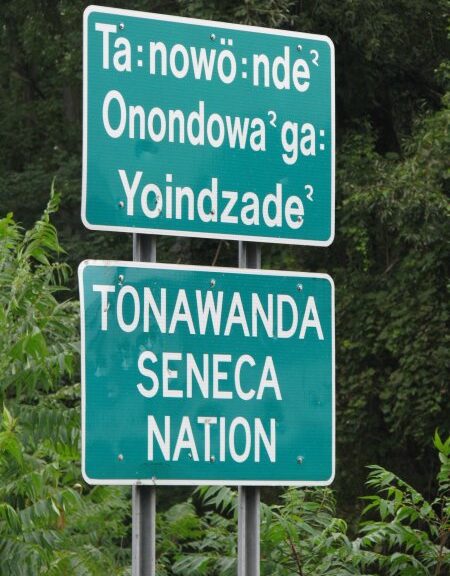

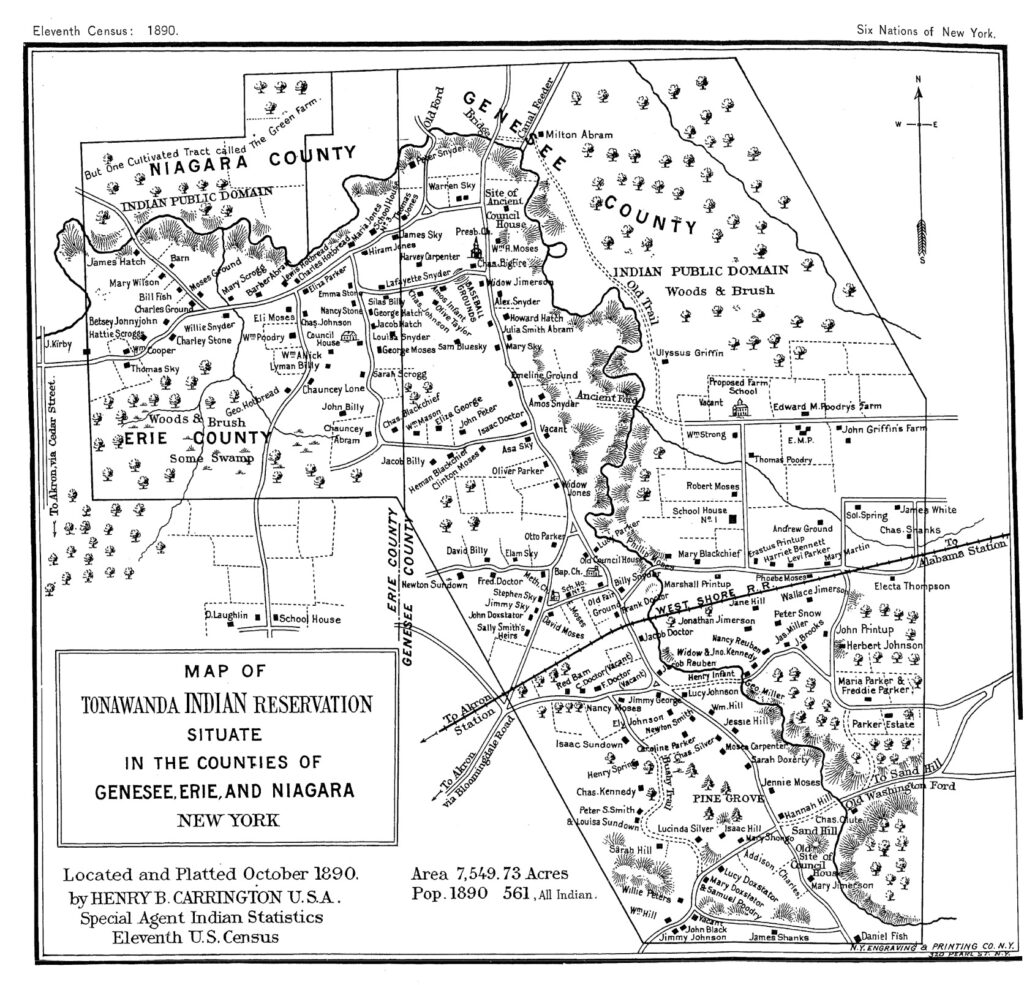

I am deeply disturbed, as a historian, by the proposed STAMP development project bordering the Tonawanda Seneca Nation territory. STAMP stands for the Science and Technology Advanced Manufacturing Park which will be built on the margins of the Tonawanda Seneca Nation. It’s another “Buffalo Billion boondoggle,” one journalist pointed out, a manufacturing facility boosted by the Genesee County Center for Economic Development that will, when built, damage wildlife habitat and the ways of living of the Tonawanda Seneca Nation. Millions have been spent, but not much has been accomplished yet. A hearing will be held tonight, Thursday, May 11th, at the Fire Hall in the Town of Alabama, New York.

I will leave it to those with expertise in the field to describe the significant ecological and environmental consequences of the project, though they seem quite significant and have not been persuasively addressed by the developer. What I would like to describe to you is the history of this state, and its long history of interactions with Native American Nations. New York could not have taken its current shape without a systematic program of Indigenous dispossession that at times explicitly violated the laws of the United States, and always basic standards of justice, honesty, and equity.

It is history in which the State of New York has consistently attempted to skim the cream off of whatever prosperity develops on Indigenous land; has aided and abetted in the environmental devastation of Indigenous homelands, and pursued on or around Native American communities projects that their NIMBY white constituents refuse to countenance in their own neck of the woods. It is a history of despoliation, devastation, and avarice, that is appalling even without reference to state boarding schools, military campaigns, and dishonesty in its dealing with the Indigenous Nations. Will the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation participate, once again, in this long and, frankly racist history? I hope that they will turn the page, write a new chapter, and look to a better future.

I am not optimistic. Governor Hochul has been no friend to the State’s Indigenous peoples. She presides over a state built on stolen land. One thing that Democrats and Republicans can agree on is that there shall never be a meaningful accounting. New York became the Empire State through a systematic program of Iroquois dispossession. That’s a fact. Though the Supreme Court declined to do anything about the process, arguing disingenuously that the injuries occurred too long ago to offer a workable remedy, most of the so-called treaties the state negotiated clearly violated federal law.

Not only were many of these transactions unambiguously illegal, but they were, as the kids say, as shady as hell. The Onondagas and Oneidas, for instance, entered into agreements in 1788 in which they were led to believe they would lease their lands to the State of New York. Turns out that when the treaty was written by New York officials, those leases had magically been transformed into sales. Dispossession through literacy in English. Other transactions took place with small number of Indians present, few of whom were the proper people to sign treaties. And the United States, especially with regard to the Senecas, hardly kept its hands clean. The 1838 treaty of Buffalo Creek, a transaction designed to expel the Six Nations from New York State, is the most crooked treaty in the history of this country. That is saying something. Signatories were coerced or threatened, signatures were forged, and alcohol flowed freely. Meanwhile, both federal and state authorities in New York have ignored the treaty provisions that protect Indigenous rights. For example, clauses guaranteeing the Senecas and their Iroquois neighbors the right to the “free use and enjoyment of their lands” in the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua have been consistently ignored. They have ignored provisions in treaties guaranteeing Indigenous peoples the right to hunt and fish on the land they ceded to the state. The state has even tried to tax the “per capita” payments the Seneca Nation made to its members from the Nation’s gaming proceeds. It is just one assault after another.

It is worth keeping in mind that the Seneca Nation has never asked for special privileges. It asked merely that the state of New York follow the rules to which it had agreed. Contracts are sacred, Governor Hochul suggested when she extorted the funding she needed to secure a new stadium for the Buffalo Bills, unless they somehow limit her ability to funnel many millions of public dollars to private hands.There is a principle that is very important to Iroquois people. The People who made up the Iroquois League conducted their lives in accordance with this principle over the centuries. It is called “Guswenta,” and today it is represented by a very specific wampum belt known as the Two-Row, which depicts two parallel lines on a field of white. The lines represent the Iroquois and their non-native neighbors. They shared the same land, they occupy the same country, but they remain independent and autonomous. The lines do not cross, and neither natives nor newcomers should interfere in the affairs of the other. Indigenous peoples in this state have kept their part of the bargain. They have had little choice. The state, and its colonial predecessors, have not.

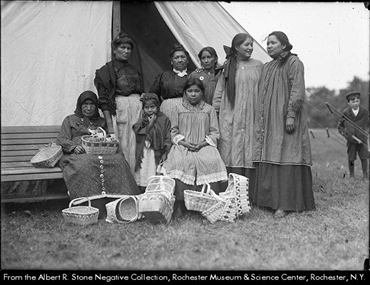

The Indigenous people of this state have faced epidemic diseases, military invasions, the carrying away of their children to boarding schools, and systematic and deliberate attempts to wipe out their culture and take their land. Yet here they remain, developing their communities, looking forward, in a state that has been a steady and relentless adversary. They hoped the state would play by its own rules. Governor Hochul always has said no. She will support the elimination of Native American mascots–that costs her nothing–but when the rubber hits the road she is as Anti-Indian as they get.

So when a developer hopes to gain state support for an exchange of 665 acres of habitat linked by forests and wetlands to the Tonawanda Seneca Nation for fifty-eight acres of non-contiguous land and claims that it is an equivalent property and that the exchange will actually benefit the ecosystem, and when the developer ignores completely impacts on the Nation and its people, it is hard not to be skeptical. What is easy to see is yet another chapter in the State’s long, brutal, and exploitative history towards Indigenous peoples. The proposed swap is about so much more than economics. It makes a mockery of “consultation,” endangers endangered species, and is so patently inequitable that it is impossible to take seriously.

But all of this is very serious. Industrial development at STAMP will disrupt the Tonawanda Seneca Nation’s ability to engage in the free exercise of their traditional beliefs. By damaging the Big Woods, where medicines are harvested and subsistence hunting and fishing takes place, it threatens directly the health and welfare of the Tonawanda Seneca Nation and the Haudenosaunee, who with Tonawanda’s permission hunt, fish, and gather there too. A long time ago, New York Indians were told to give up their lands in New York for a sliver of desiccated earth in Kansas. The land out there in the west, American officials, New York businessmen, and white racists argued, is just as good as what you have in New York. It’s the same, these promoters of ethnic cleansing optimistically point out. Except that it was not alike at all, just like 58 non-contiguous acres is not at all the same as 665 acres of culturally significant and environmentally and ecologically sensitive land.

The Tonawanda Seneca Nation always has resisted the calls of wealthy New York developers, from Robert Morris in the 1790s to today, that they leave their homelands. In the 1838 Treaty of Buffalo Creek, the Tonawandas were surprised to learn their reservation had been given up, even though they were not parties to the treaty. Two decades later they were able to purchase back a portion of the reservation they never had consented to sell. They were ripped off, but they hung on, preserving their culture and their political system within a state that has historically respected that culture not at all. If any number of white people had their way, the Tonawanda Seneca Nation would no longer exist—their language, their religion, the land, their people—all would have been absorbed by the ceaseless State of New York.

The DEC will support the state’s long-standing racism towards Indigenous peoples if it supports this habitat destruction. Tonawanda Senecas, you see, want nothing more than for the State of New York to keep its word and leave them alone. This is the case for other Haudenosaunee peoples. But here we go again, the relentless drumbeat of exploitation, avarice, and racism. Tonawanda claims to the significance of the land and the species that live there are dismissed and shown no real respect.

I have been to hearings like the one that will be held this evening in the Alabama Fire Hall in the town of Alabama, New York. There is no meaningful “consultation” at meetings like this: the DEC officials sit at a table, fidget with their phones, as they listen uncomfortably to Indigenous peoples describe yet another assault on who they are and what they hope to become. I hope that this time, the members of the DEC in attendance will listen to what the Tonawandas say, and try to hear the sentiment beside it. I hope that they will put a stop to this ill-conceived and poorly thought-out industrial manufacturing development. I hope that they will break with a horrible history and, in the spirit of trust and reconciliation, seek pardon for the unresolved crimes of New York’s past.