In conversations with colleagues across the country at the American Society for Ethnohistory meeting in Tallahassee, one thing we all agreed on was that our students seem to be reading less, and reading less closely. Participation in class discussions had declined, as had attendance. I was disappointed in myself in that I had not succeeded in breaking through, in getting students to engage with the material and do the reading, but I was reassured, I guess, that I as not alone. Still, I had to try something new.

It went really, really well.

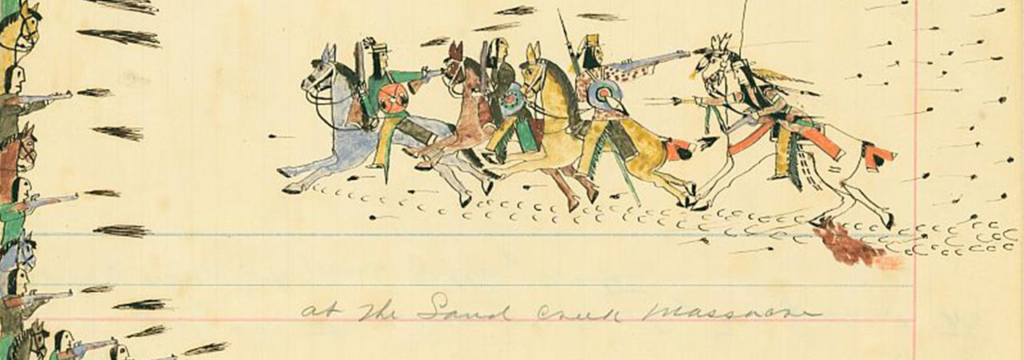

We were discussing some particularly brutal stories from the Plains Wars during the Civil War Years, beginning with the Dakota Uprising in Minnesota and closing with the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. They could read about both events in Native America, but I wanted them to go deeper into the material. I recently read a fantastic article by historian and artist Taylor Spence called “Rethinking the Colonial Encounter in the Age of Trauma.” He is a great historian. His essay appeared in a really useful volume entitled The Routledge Companion to Global Indigenous History. Both the article and the book are well-worth your time. Spence suggested to me a new way to teach this subject, a trauma-informed approach that could lead students to feel deeply the impact of the events they were reading about. Following Spence’s lead, I assigned them Waziyatawin’s “Grandmother to Granddaughter: Generations of Oral History in a Dakota Family,” which appeared in the American Indian Quarterly back in 1996. Waziyatawin (Angela Cavender Wilson) wrote a searing piece of family history. I suggest you try it in your courses.

Waziyatawin’s grandmother, Elsie Cavender, had received a story from her grandmother that she shared late in life. She told Waziyatawin of the family’s forced march after the Dakota Uprising, and how soldiers, in an act of irrational and senseless violence, murdered Elsie’s great-great-grandmother. It’s a brief essay, and Elsie Cavender’s account is roughly a page and a half. I asked my students to tell me what happened. They gave me a competent summary of the story. The Dakotas were marching towards imprisonment at Fort Snelling. They confronted white people in towns “where the people were real hostile to them.” They white people threw rocks, and poured scalding water on them. They camped at night, living on rotten provisions provided by the army. They marched onward. They moved too slowly. The soldiers grew angry, and stabbed Elsie’s Grandmother’s grandmother with a saber. She bled to death on a bridge. When her family returned later, the body was gone, but they saw dried blood on the wooden planks.

I told the students I wanted more. Go deeper. Summarizing what you read, after all, is no great achievement. Spence suggested that the students attempt to imagine deeply what it would have been like to be present when those soldiers murdered an elderly woman for no reason at all. So I told them to think of their senses. If they were on the bridge where the killing took place that day, what would they have seen, heard, smelled, tasted or felt?

My students jumped into the assignment. You would smell the rotten provisions the soldiers distributed, one student observed. The relentlessly irritating sound of the squeaky wagon wheel, another pointed out. They would have heard that. The dust, the sight and smell and sound of the cattle would have been difficult to miss. They were rolling now, but they were staying away from the violence. It took them a bit, but they got there. The soldiers’ profanities, their angry, barking orders in a language the Lakotas did not understand; the screams in response to unbelievable and senseless violence; the blood pouring from a mortal wound.

We had spoken early that day about the reliability of oral testimony as evidence. One student predictably and appropriately suggested that it might be like the old game of Telephone, as a story changes as it is passed from one hearer to another. But think of each of the sensory events you just identified, I told the students. I asked them to think of their earliest memories. What made those memories particularly powerful? Each of them, individually, affected the senses in a memorable fashion. Each was easily capable of etching itself into the minds of successive generations of storytellers. The events that Waziyatawin recalled for us, I suggested, were of the sort that would not be easily forgotten.

We are not supposed to teach history in a way that makes our students feel bad about who or what they are. We should not make them feel guilty or uncomfortable about the past. That is what lawmakers in a growing number of red states have demanded. They have proscribed the teaching of certain topics. They have singled out the 1619 Project, and the histories of slavery, and racism, as topics that should not be taught in ways that make white people feel uncomfortable. These right-wing politicians have said much less about Native American history, but clearly they would be bothered by things I teach in my classes: the Paxton Boys, for instance, or the massacre at Gnadenhutten. These politicians are calling for an education fit for sociopaths. They want students to feel nothing but love of country.

My students felt badly about the history they read that day. Again, some of them had tears in their eyes. When they read Silas Soule’s account of Sand Creek, in which he describes the mutilation of dead Cheyenne and Arapaho women and children, well, they felt this as well.

But here’s the thing. They felt badly, to be sure, but they did not feel ashamed of their race. They did not feel guilty or responsible for the crimes of the past. This is what the Republican dingbats miss. My students felt connected to people very different from them who lived a century and a half ago. They understood the meaning a past event at a much deeper level than they may have done previously, and the emotions were heavy indeed. They grieved. They had, I would argue, learned a lot. I sent a message to Dr. Spence to tell him how well his class exercise went, how much my students learned, and how thankful I was for his good work.

Let’s say you are walking down a crowded city street. Your foot catches a person walking in front of you, and they trip and almost fall. Without thinking, if you are a decent person, you apologize. You are not debasing yourself when you do this. You worried that you might have hurt somebody, that they could have fallen and been injured. It’s not about you. You apologize because you are not a dick, because you care about other people, because you worry that your actions could have caused for someone pain or sorrow. You say you are sorry because you felt sorrow.

I have thought about this a lot when I teach. Why do we say sorry? I want my students to appreciate the past on its own terms, to feel a connection to the people they read about. The students in my class obviously could not undo the past. They could not apologize or express their sorrow to the Dakota woman murdered on that bridge. But they did understand something at a deeper level than they might otherwise have done, and that made them wiser and more capable of understanding other people. They felt empathy. And they cared about this particular piece of the past more deeply that they would have done if I had merely told them about the Dakota Uprising and Sand Creek. They may not remember much of my class a couple of years from now but I am confident that they will remember this.