My college does a territorial acknowledgment before many public events on campus. We are not alone in doing this. We acknowledge that SUNY-Geneseo stands in the historic homeland of the Seneca Nation of Indians and the Tonawanda Seneca Nation. It is an important first step, but one for which my feelings are ambivalent. We do this acknowledgment in rooms where no Native American students are present. We do it for ourselves.

During our commencement ceremony, a Haudenosaunee flag stands on stage and another flies in our student union, beside the flags of all our foreign students’ nations. Only a tiny number of Native American students have walked the stage at commencement, or ambled through the Union. We consulted with no Indigenous peoples when we began acknowledging our location at the Western Door of the Iroquois Longhouse.

A just-announced diversity initiative will lead to a more public celebration of Indigenous Peoples’ Day, something we so quietly recognized several years back that it is as if we do not want anyone to know. And we will not raise the Haudenosaunee flag on the college flagpole, unlike some of our sister institutions in SUNY.

So let’s get serious for a second. During a troubling year when the college has dedicated itself to exploring the difficult question of how we might become an anti-racist campus, what we have done with and for Indigenous peoples is simply not enough. We are quiet crusaders on the cheap. Our gestures, and that is all they are—have been tiny and few and they cost us nothing. We talk a good game, but that’s it. To say that we acknowledge that our college stands on what was once Indigenous land at a college that makes little effort to recruit, support, and retain Indigenous students is about as hollow a thing as I can imagine. And believe me, there are many schools—in SUNY and beyond– that do even less than us

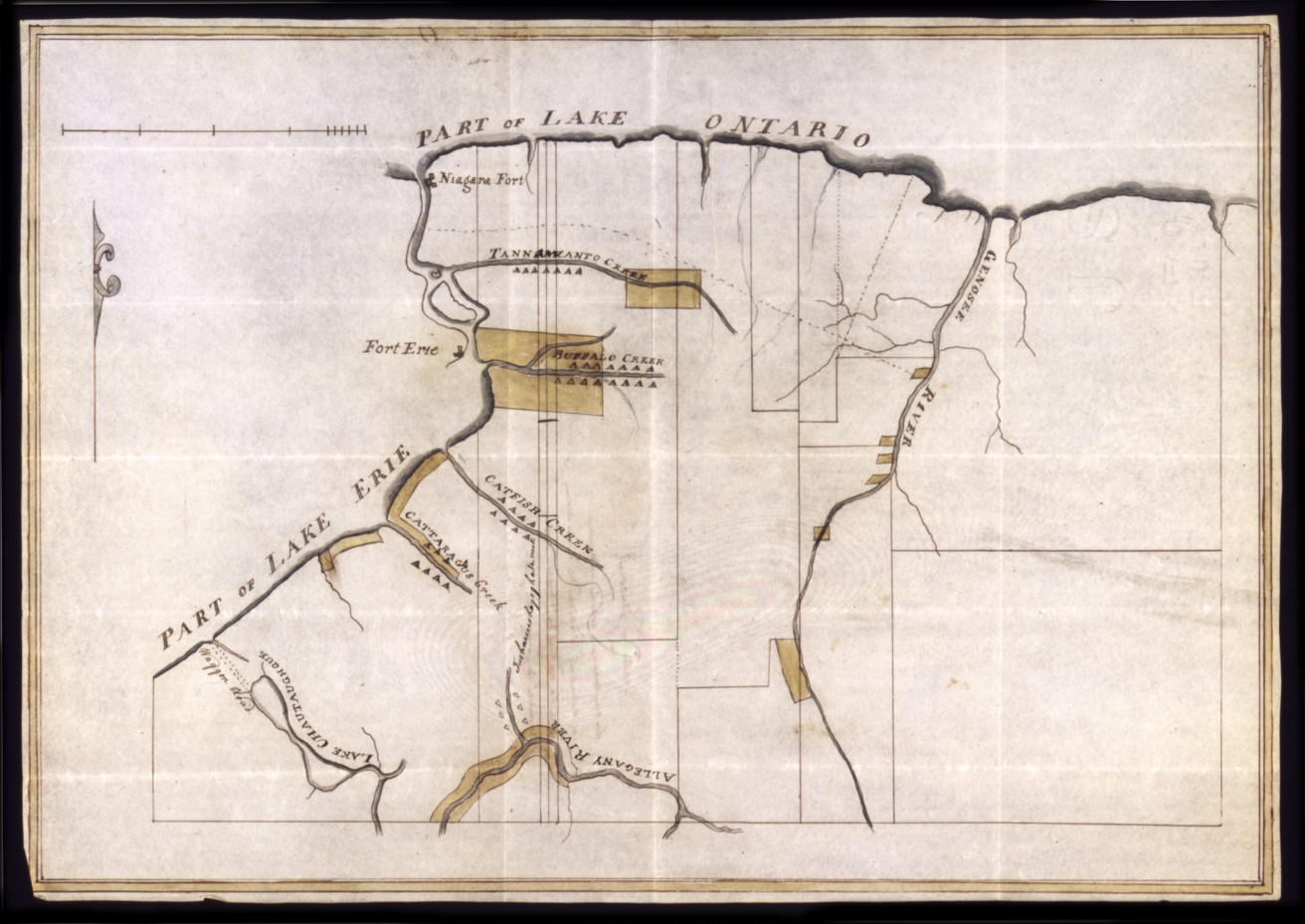

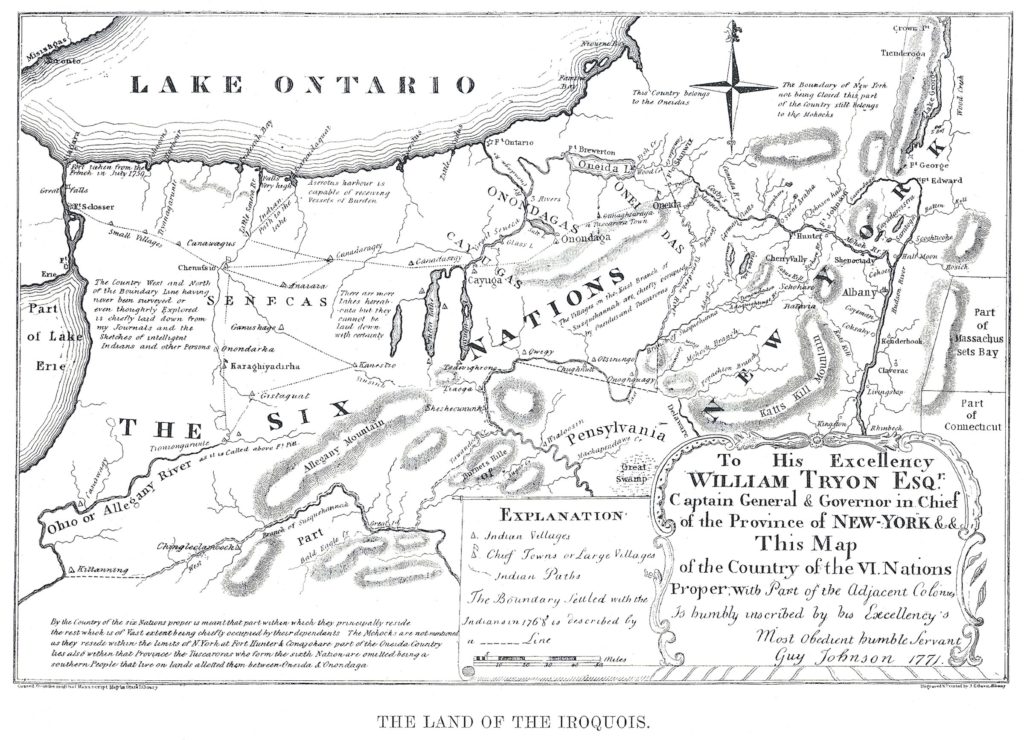

GENESEO, more than many colleges across North America, stands directly on Native American land. “Chenussio” appears in New York’s colonial records and in the writings of French Jesuit missionaries in the middle of the seventeenth century. The Genesee Valley, the beauty of which we sing in our college’s song, was a hub of indigenous activity for many centuries. Geneseo stands directly at the Western Door of the Haudenosaunee longhouse and critical events in Seneca history took place near and on the very ground the campus occupies. The Big Tree Treaty of 1797, for instance, was negotiated in one of our parking lots. The Senecas there signed away all their lands in western New York, from that gorgeous Genesee river valley to Lake Erie, eleven small reservations excepted. The town’s white founding fathers all were involved in dispossessing the Senecas. We occupy what was a major Seneca town site in a state that could not have taken the shape it now holds without a systematic program of Iroquois dispossession. It can be argued that no SUNY school stands on ground so closely linked to that history of dispossession.

I am completely familiar with the arguments that will be thrown back at me. I have heard them many times. Indigenous peoples comprise approximately 1% of New York’s population. It is not worth the trouble to devote our scarce resources to trying to attract these students to campus and make them feel welcome once they arrive. Our dedication to diversity is highly qualified, indeed. We cannot fly the Haudenosaunee flag on the campus flag pole and we certainly cannot invite our Haudenosaunee neighbors to campus, because that will anger anti-Indian politicians in Albany and thus jeopardize the funding needed to fix a college that has significant construction and maintenance needs. We will not look down at the ground upon which we stand. We can’t. Because. We can’t. Because. We just can’t. We won’t.

Several years ago I organized a meeting on campus. I invited a number of Haudenosaunee scholars from other SUNY campuses in the western part of the state. They came to Geneseo to talk about bringing Indigenous students to SUNY. The four of us agreed that it was simply a choice. If our colleges wanted to do it, they could. If SUNY as a system wants to do it, it can. And despite invitations sent to the entire administration and admissions staff, we spoke to an empty room. It was difficult to escape the conclusion that our leaders at that time had voted with their feet.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my colleagues and I love my students. I have good friends across the campus. But I’ve been at Geneseo for a while now, and I think I see many things clearly. We do not do enough. We choose not to do enough. We are not interested in doing enough. It pains me to write these words.

What would I have the college do? I have been asked that. I am a professor. I am a very good teacher. I have been successful as a scholar and I continue to try to produce. I write more than most historians in SUNY. And I do a lot of service, both on and off the campus. This service work is time consuming and tiring, as it forces me to be on the road at least every other week. At one level, then, my response to questions like this—to those in admissions, student services, in recruitment and retention who pose it— is to tell them to figure it out for yourselves. You get paid more than I do. You are the experts. Do the work. I am already too busy. Hire someone with some expertise in recruiting Native American students.

But that isn’t how it works, is it.

If you are a BIPOC professor, of course you know this. Even if you are a white guy like me who stumbled into this work long ago and was lucky enough to be welcomed into the communities about which I teach and write, you are asked to do nothing less than come up with solutions to the problems you clearly see, and to do so without any additional compensation. It is demoralizing. So we are asked for solutions. We propose solutions. And those solutions are shot down. We can’t. Because. We can’t. Because. We just can’t.

We won’t.

It is a choice. It is really that simple. But the least we can do is try. We can redirect funds. It is the moral and ethical thing to do. Hire Haudenosaunee faculty and staff. Create a safe and welcoming environment on campus with student services staff experienced in the needs and concerns of Indigenous students. Grant free tuition, room, and board to Haudenosaunee students. That might be a start. We could do this easily for the cost of SUNY’s football programs. We send no one to meet with Native Nations. We have no one in student services to help support those students should they arrive. We could divert resources towards this goal if we wanted to. We could acknowledge our college’s historic location with something more than a few lines tossed out at the beginning of college functions. We are well-intentioned but ineffective.

OUR ENROLLMENT is down significantly this year, which has made an already desperate financial situation even worse. The pandemic and widespread economic dislocation is responsible, but some of our administrators fear that those students are not coming back. Meanwhile, we continue to promote the image, with some small justification, that we are the poor person’s Swarthmore, an elite liberal arts college at a public school price. Sadly, I do not see us casting our net in new waters to try to bring students to Geneseo who we have not brought before. I see no evidence that we are interested in recruiting kids from the inner-city and I see no effort to reach out systematically to the state’s indigenous population. Indeed, we had a recent alum from the Tuscarora Reservation who wanted nothing more than to recruit and mentor Haudenosaunee students for Geneseo, and he would have been good at it. Nobody in Admissions at that time was interested. (Most of those people have since moved on to other colleges). Geneseo is well known as a demanding school that offers difficult courses. Yet our retention rate—the number of students who come to Geneseo and return—is low. Clearly many of us need to change the way that we teach. But we also need to think about who our students are, and where we are going to look for new ones. This is difficult work that will not yield results immediately. It will take resources that are in short supply. But how we expend our resources is a choice and we really ought to choose differently, as a college and as a massive University system. As employees of the State of New York, we ought to recognize how complicated the State’s relations have been with Native Nations, and how complicit our employer has been in the historic dispossession and marginalization of the state’s Indigenous population. With regard to our native neighbors, the state’s hands are dirty, and that dirt will not be washed away by a few lines thrown out at the beginning of campus functions.