The anniversary of the “Treaty of Big Tree,” signed on the 15th of September in 1797, is approaching. According to a New York State historical marker, the agreement was negotiated on land that now provides parking for students who attend the college where I teach. It is a big deal in Geneseo. It is the one, big, historical event that occurred within the town’s bounds.

One thing that I think a lot of non-historians do not realize is the amount of research we do that never sees the light of day. Although we require our students quite often to come up with some meaningful sort of research project during the short fifteen weeks of a semester, we spend plenty of time following interesting questions that lead to dead ends. It happens all the time. We are curious. We ask questions and, sometimes, despite our best efforts, we cannot find an answer.

A couple of years back I was asked to do some research for the Seneca Nation of Indians about the history of the annuities that often were attached to the agreements they entered into with New York State and the United States. In exchange for their lands, Senecas would receive an annual payment.

I often see this bumper sticker in and around Indian Country. The Indian Country Today Media Network, now apparently on hiatus, spoke frequently of broken treaties. But some treaties, it must be remembered, were little more than real estate transactions in which white people obtained a title to Indian lands in return for very little at all.

I have always done research on Big Tree, but I had never bothered to look at whether the United States had fulfilled its part of the bargain. Certainly it acquired a lot of land. But did it pay to the Senecas what they were owed? I travel with footnotes.

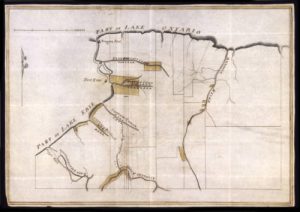

I tell the story of the treaty at Big Tree in Native America. It is an important moment in the history of the Senecas. Robert Morris had acquired from earlier land speculators a right of preemption, or first purchase, to all the Seneca lands in New York state. He sold this right to the Holland Land Company in December of 1792.[1] A well-financed syndicate of Dutch merchants and bankers, the Holland Land Company was much better equipped than Morris to oversee the actual opening up of the Seneca homeland to white invasion and settlement—a massive undertaking that involved administering an enormous territory, and absorbing the costs associated with surveying, building roads, and laying out towns.[2] Before they would pay, however, the Holland investors insisted that Morris extinguish the Senecas’ title to the lands in question.

What did that mean? It meant holding a treaty, and negotiating with the Senecas. In 1797 Morris began laying plans for a council. Because Morris was ill and because he feared prosecution for debt should he leave his home in Philadelphia, his son Thomas traveled to Big Tree on the Genesee River to conduct the treaty. (The treaty was held, according to a New York State historical marker, near one of the parking lots on my campus). The story of this sordid council, involving the use of alcohol at the treaty ground and the bribing of important Seneca leaders, has been told many times before. My treatment in Native America is inspired by the great books written by Anthony F. C. Wallace and Laurence Hauptman, which are required reading for those who wish to understand the Iroquois.[3]

Morris obeyed the letter, if not the spirit, of the federal Indian Trade and Intercourse Law, the statute which governed relations between natives and non-natives. The law required that for a purchase of Indian lands to be legally valid, the purchase must be overseen by the United States, and the resulting agreement must be approved by the United States Senate. Morris requested and obtained the appointment of a federal agent, and the Senate did ratify the agreement. And at Big Tree, on the campus where I offer my courses in Iroquois history, the Senecas parted with all of their land, that huge region from the Genesee River westward to the Great Lakes and the Niagara River, save for 200,000 acres distributed across eleven reservations. In exchange for this massive cession, Morris agreed to pay “the sum of one hundred thousand dollars, to be by the said Robert Morris vested in the stock of the bank of the United States, and held in the name of the President of the United States, for the use and behoof of the said nation of Indians.” The Senecas would receive as a payment, each year, the interest earned on this investment.[4]

So let’s follow that money, as far as the sources allow. That was easier said than done. I am no accountant.

In March of 1798 the United States used the $100,000 it had received from Robert Morris to purchase 205 shares in stock of the Bank of the United States “to be held in trust” for the Senecas “by the President of the United States.” The dividends on this investment averaged slightly more than seven thousand dollars a year, though some of the revenues that would otherwise have been delivered to the Senecas were withheld to purchase additional stock: 9 shares in 1804 at a cost of $5328.00, an additional share in 1806 for $522.00, and five more shares in 1807 for a sum of $2580.00. With the exception of this combined amount of 8430 dollars, the increase produced by the Big Tree investment was delivered to the Senecas by federal agents. The dividend, paid twice a year, amounted to a minimum of sixteen dollars per share between 1798 and 1802, or $3280 every six months.[5]

The Bank of the United States, part of Alexander Hamilton’s (Stop singing, please) ambitious but controversial program for developing the new nation’s economy, had received a twenty-year charter from Congress in 1791. When the Bank ceased its operations in 1811, the stock was liquidated, producing a sum of $95,040. (This sum was less than the $100,000 initially invested owing to shifts in the value of the stock). The War Department credited $1980.00 of this sum to fund its Indian appropriations account, while investing the remaining $93,060.00 in 6% stocks in the name of the President of the United States, to be held in trust for the Seneca Indians.

The Senecas watched closely these funds, and saw the annual dividend as essential to their survival. They said this, in writing, time and again. A large group of “Seneca chiefs” told Secretary of War William Eustis in 1811, after the expiration of the Bank’s charter, that “we are told the field where our Money was planted is become barren.” What they hell, they seemed to be saying. This concerned the Senecas, the chiefs said, because “our money has heretofore been of great service to us. It has helpt us to support our old People, and our Women and Children.” The Senecas sought assurance that the Big Tree fund—the result of their leaders’ difficult decision to transform their lands in western New York into an annual payment—would continue to be paid. “Brother,” the chiefs wrote to Eustis, “we do not understand your ways of doing business,” and “this think is heavy on our minds.” The Senecas wanted to continue “to hold our White Brethren of the United States by the hand, but this weight is heavy. We hope,” they concluded, that “you will remove it.”[6]

I am fairly certain that these Seneca chiefs understood more than they let on. Signed by a large number of prominent Seneca leaders, the “Talk of the Seneca Chiefs” must have occasioned some alarm in the War Department. With war with Great Britain looming, the chiefs suggested that if the United States did not uphold its part of the bargain and see to the continued payment of the dividends, they might then cease “to hold our White Brethren of the United States by the hand,” and instead embrace those other white brethren, who stood poised on the opposite side of the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, with whom they had aligned during American Revolution. Don’t mess with us. You need us to help secure the Niagara frontier.

The interest earned on the investment after 1811 produced only $5618 per year, but owing to the importance of the Senecas as allies while the United States muddled through its conflict with England, the sum of $6000 was paid to them from the general funds of the Indian department. This fund, in turn, was credited with the dividend produced by the stock. This arrangement continued until 1826 when the 6% stock was liquidated, producing $93,602.67, which the War Department invested in 3% stock. The dividends, falling well short of the $6000 to which the Senecas had grown accustomed, posed a problem for the administration of John Quincy Adams. To pay the usual $6000 would draw down the fund and perhaps force the sale of the stock from which the dividends derived. In any case, the government would be expending more than the interest on the investment. President Adams determined nonetheless “that the government would continue to pay” the Senecas six thousand dollars annually, “taking upon itself the protection of the fund.” The United States, Adams believed, “was bound in good faith to do so.”[7]

Adams was willing to spend federal funds to uphold the honor of the United States. His successor, Andrew Jackson, clearly did not share this view. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Thomas McKenney disliked the idea of paying the $6000.00 when “the sum remitted” was “greater than the interest received on the Stock.” Anticipating the new president’s views, McKenney decided to offer to the Senecas in 1829 nothing more than the divided, a sum of less than three thousand dollars by 1829.[8]

This unilateral decision angered the Senecas. An elderly Cornplanter, writing from Kinzua, appealed to President Jackson. The Senecas, Cornplanter wrote, had been well satisfied with the annual dividend of $6000, but now the news from Washington “fills our minds with concern that we cannot get our Money nor be informed why we should not receive [it] as in former years.”[9] Writing less than three weeks after Congress enacted the Indian Removal Bill, surely Cornplanter recognized that he had directed his appeal to an ardent expansionist who coveted Indian land and wanted all eastern Indians relocated to new lands in the west. The Big Tree payment, Cornplanter continued, “was but a little but it enabled us to purchase Salt & some Blanketts and that would be a great help to those who are active & till their land.” The Senecas could not accept anything less than the 6% to which they were accustomed.[10]

The President did not believe that any law existed which authorized him to pay to the Senecas a sum greater than the value produced by the stock. Sticking to his rigid and self-serving code of constitutional interpretation, Jackson punted the question to Congress, which in the 1830s did things. The resulting bill, introduced in the House of Representatives, would provide the Senecas with a permanent annuity of $6000, while whatever proceeds emerged from the stock would be credited to the United States.

Senator John Forsyth of Georgia, a determined advocate of the ethnic cleansing his state carried out against the Cherokees and the Creeks, opposed any measure that went beyond the strict language of the Big Tree treaty. Nothing in that agreement, he believed, obligated the United States to pay to the Senecas 6% forever. Paying the $6000 he said,

had already cost the Government a very considerable amount over and above the product of the stock, and now the question arises, are we bound to do more, after doing all we have already gratuitously performed? But it is said the Indians have been given to understand that the full amount of six thousand dollars should be paid to them. Who gave them to understand this? Who had a right to do so? And yet it was on such loose declarations that the whole merits of this claim seemed to rest. It is contended that the Government is bound to realize to these Indians any expectations they may have been induced to entertain. It is true, it is said that the late President of the United States [Adams], when the subject was before him, had given them these assurances. This, however, did not establish the justice of the demand. He could see no sort of obligation on the part of the Government to pay them more than the amount produced by their stock.[11]

Forsyth’s argument failed to persuade a critical number of his colleagues, which is surprising given how they felt about Indians, and the bill became law in February of 1831. Thereafter, the law read,

the proceeds of the sum of one hundred thousand dollars, being the amount placed in the hands of the President of the United States, in trust, for the Seneca tribe of Indians, situated in the State of New York, be hereafter passed to the credit of the Indian appropriation fund; and that the Secretary of War be authorized to receive, and pay over to the Seneca tribe of Indians, the sum of six thousand dollars annually, in the way and manner as heretofore practiced.

A subsequent act, signed into law in December of 1831, paid to the Senecas $2914.40, “that being the balance due on the annuity payable to said Indians for the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty-nine.”[12]

Congress did on a number of subsequent occasions revisit the Big Tree annuity. An act passed in June of 1846 provided that “certain stocks, etc. held in trust for the Senecas should be cancelled and the funds deposited in the Treasury at 5 percent interest and the interest paid to the Senecas annually.”[13] Fifty-three years later, in March of 1909, Congress directed the Secretary of the Treasury to place on the books of the  Treasury Department “to the credit of the Seneca Indians of New York, the sum of $118,050, such sum to bear interest at 5 percent until withdrawn for the Indians, being the value of stocks held in trust for the Indians and taken by the United States and cancelled under the authority of the act of June 27, 1846.” Congress authorized the Treasury Secretary in 1909 to place on the books of the treasury department $118,050, “such sum to bear interest at 5 percent until withdrawn for the Indians, being the value of stocks held in trust for the Indians and taken by the United States and cancelled under the authority” of the 1846 act. This sum, Congress decided, the Treasury secretary would pay “per capita to the members of the tribe entitled thereto.”[14]

Treasury Department “to the credit of the Seneca Indians of New York, the sum of $118,050, such sum to bear interest at 5 percent until withdrawn for the Indians, being the value of stocks held in trust for the Indians and taken by the United States and cancelled under the authority of the act of June 27, 1846.” Congress authorized the Treasury Secretary in 1909 to place on the books of the treasury department $118,050, “such sum to bear interest at 5 percent until withdrawn for the Indians, being the value of stocks held in trust for the Indians and taken by the United States and cancelled under the authority” of the 1846 act. This sum, Congress decided, the Treasury secretary would pay “per capita to the members of the tribe entitled thereto.”[14]

I am not sure what happened as we carry the story through the rest of the nineteenth century and into and through the twentieth. The records of congressional appropriations show that the Congress continued to appropriate the $6000 dollars each year to pay its obligations under the Big Tree treaty. Seneca Nation records, however, suggest that these payments were not received until relatively recently. I still have work to do to be able to sort this out.

But here is the thing. Honor Indian Treaties. But a lot of them were not honorable at all, and the terms of many of them were never written with Indians’ interests in mind. Students in my Native American Survey course has just finished reading Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian, which says so much in such a breezy manner. “Treaties,” King wrote, “were not vehicles for protecting land or even sharing land.” Rather, “they were vehicles for acquiring land. Almost without fail, throughout the history of North America, every time Indians signed at reaty with Whites, Indians lost land.”

So let’s think about what we mean when we call upon the United States to honor its treaties. Certainly the government should keep its word. Certainly in the realm of Indian affairs it has behaved despicably and irresponsibly. Certainly treaties have been broken many times, with often devastating consequences. But, in many instances, native communities would have been better off if these treaties had never been negotiated, never signed, never ratified, and never proclaimed by the president. So many of them were coerced, or fraudulent, or exploitative. The colonization of this continent, and the dispossession of native peoples, to a great extent was achieved through the instrument of treaties.

[1] Charles E. Brooks, Frontier Settlement and the Market Revolution: The Holland Land Purchase, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 13-14.

[2] Wallace, Death and Rebirth of the Seneca, 179-180. The Holland Land Company Papers are located at the State University of New York, College at Fredonia.

[3] Wallace, Death and Rebirth of the Seneca, 179-183; Taylor, Divided Ground, 313-316; Laurence M. Hauptman, Conspiracy of Interests: Iroquois Dispossession and the Rise of New York State, (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997), 91-92; Norman B. Wilkinson, “Robert Morris and the Treaty of Big Tree,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 40 (September 1953), 257-278.

[4] Kappler, comp., Treaties, 1028.

[5] LR OSW IA, 1: 0188.

[6] Talk of the Seneca Chiefs, 9 October 1811, LR OSW IA, 1: 714.

[7] Nourse Report, 18 March 1829, LR OIA-Seneca, Roll 808.

[8] McKenney to Secretary of War John H. Eaton, 17 March 1829, Ibid.

[9] John O’Bail (Cornplanter) to Andrew Jackson, 2 August 1830, Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Gales and Seaton’s Register of Debates in Congress, 3 February 1831, p. 79.

[12] Available at the Library of Congress “Century of Lawmaking” website.

[13] “Compilation of Material Relating to the Indians of the United States, etc., by Subcommittee on Indian Affairs of the Committee of Public Lands, House of Representatives, Pursuant to H. Res. 66, 81st Congress, 2d. Sess., 13 June 1950, Serial No. 30,” in Paul G. Reilly Collection, Buffalo State College, Box 37, p. 12.

[14] Ibid., 13.