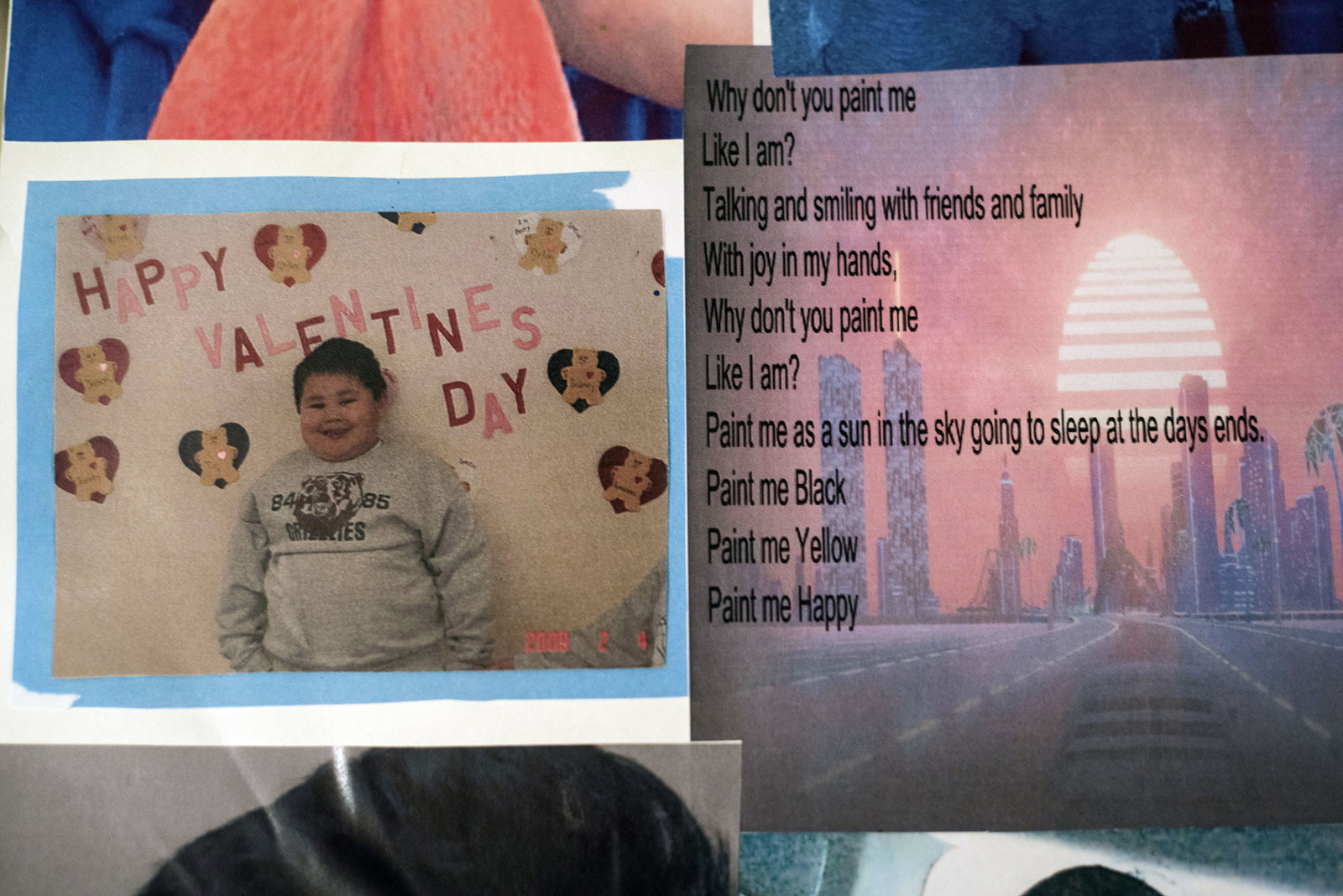

A deeply disheartening story appeared in Buzzfeed looking at relations between native peoples and local law enforcement on Wisconsin’s Bad River Reservation. It was here, last year, where a sheriff’s deputy shot to death 14-year old Jason Pero. And it is here, according to members of the Bad River community who spoke to Buzzfeed’s John Stanton, where rape, harassment, and racism are all experienced by members of the community at the hands of white law enforcement.

Stanton presents to his readers figures that you are familiar with if you have been reading my blog. According to the CDC, Stanton writes, “Native Americans are more likely to be killed during an interaction with law enforcement than any other racial group. In 2017, at least 31 indigenous people died as a result of an encounter with law enforcement. In 2016, the number was 29.”

And, he continues,

On a per-capita basis, Native Americans are 12% more likely to be killed by law enforcement officers than black Americans — and three times more likely than white Americans.

If you live on one of the dozens of reservations across the country in which local, white police forces from nearby border towns have jurisdiction, the chances that you’ll end up in jail are high. In Ashland County, for instance, Native Americans make up 11% of the population but account for 44% of the inmates in the county jail, according to data collected by the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit criminal justice research and reform group.

It is an impressive piece, and Stanton has done much more work than most journalists writing about Indian country. He looked at census data, showing the relative poverty of Bad River, and relatively high rates of unemployment. He looks at the community’s history. “You don’t have to look far back for examples of racial tensions boiling over here,” he writes.

During the Wisconsin Walleye War between 1988 and 1991, white protesters hurled racial epithets and sometimes eggs and rocks at Ojibwe tribal members spear fishing for walleye, a tradition protected under treaties between the US government and the tribe. Although the violence eventually ended after a federal judge upheld the Ojibwe right to spear fish, distrust and bitterness between the two communities remained.

According to one member of the community, things at Bad River are not as bad as they were back in the 1970s and 1980s. Whites and Indians are “inextricably linked” in Ashland County, with native peoples and their white neighbors coexisting “in an uneasy truce of convenience and routine.” The tribe’s casino is a major engine in the local economy, especially during the summer months. The system seems to work for w hite people as long as the members of the Bad River community stay quiet. But with evidence of rape, and the murder of Jason Pero by a deputy sheriff, people are speaking out. Sandra Gokee, a family relation of Jason’s and a teacher at the Ashland Middle School, was suspended for an angry Facebook post in which she lamented the murder of Jason by a deputy sheriff. According to her superintendent, Gokee created racial tensions in the school and made the children of white police officers feel unsafe.

hite people as long as the members of the Bad River community stay quiet. But with evidence of rape, and the murder of Jason Pero by a deputy sheriff, people are speaking out. Sandra Gokee, a family relation of Jason’s and a teacher at the Ashland Middle School, was suspended for an angry Facebook post in which she lamented the murder of Jason by a deputy sheriff. According to her superintendent, Gokee created racial tensions in the school and made the children of white police officers feel unsafe.

We are no longer in the 1970s and 1980s, but in the short time Our New Nero has been in office, racial tensions have increased. The small progress made over decades has been threatened.

Stanton’s fantastic article will give students a sense of the amount of racism existing in communities where native people and white people live in close contact, the ability of law enforcement to prey upon Indians with few consequences, and the complexities of law enforcement created by Public Law 280 back in the 1950s. But more than any of that, he highlights the pain caused by the murder of yet another child, by yet another law enforcement officer, in yet another incident where deadly force was hardly necessary.