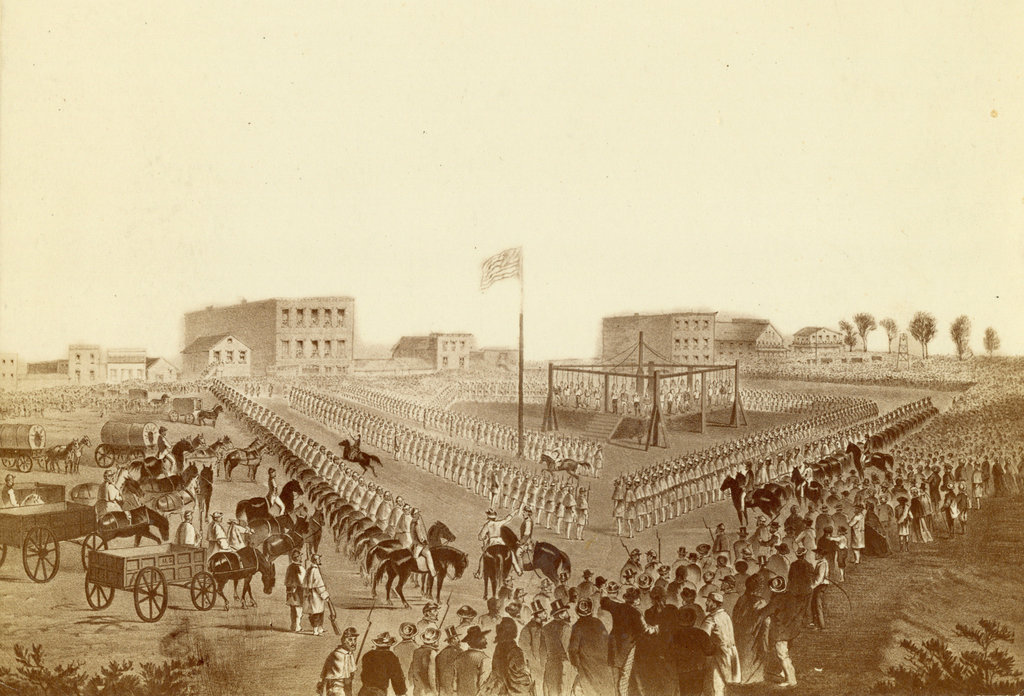

The last week in December forces those of us who study history to remember two particularly gloomy, and revealing, episodes in the Native American past. On December 29th, 1890, American soldiers massacred Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee, an atrocity for which the United States government awarded a number of medals of honor. Congress is considering legislation to revoke those awards. And on the 26th of December, 1862, American military officials executed at Mankato, Minnesota, thirty-eight Dakotas identified as “ring-leaders” in their war against the forces of American colonialism. I have been thinking about both of them over the course of the past two weeks.

There was a fair amount of commentary on these horrific events on and around their anniversaries. In reading about the execution of the Dakotas, I learned that after the execution, William W. Mayo, who later founded the world-famous Mayo Clinic, dug up at least one of the recently buried bodies of the condemned, dissected it in front of his physician colleagues, and kept the bones around his house as a child’s play thing.

I had never heard this before. I read about it in a tweet. I asked the person who posted it about the evidence. This was a stunning story, revealing in what it says about Minnesotans’ attitudes toward their native neighbors. But I could not share it with my students until I knew for sure that it was true. The person who posted suggested I visit Google; he was merely repeating something he had heard. I poked around, on Google and elsewhere, and found some news stories that demonstrated that this tale of grave-robbing and desecration was indeed true.

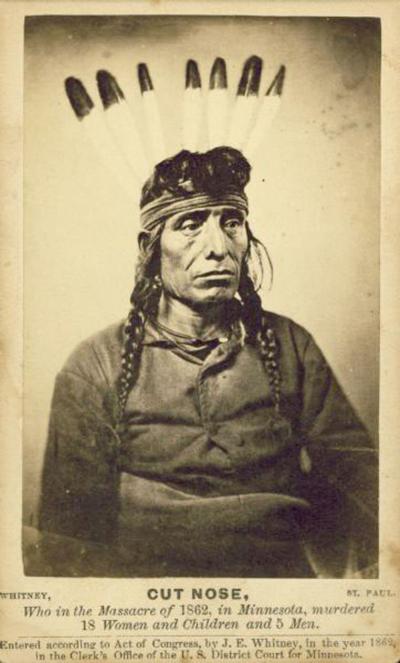

In September of 2018, the Mayo Clinic apologized for desecrating the grave and body of Marpiya Okinajin, known to the Americans as Cut Nose. His remains stayed at the Mayo Clinic until 2000, when they were repatriated and reburied. Jeffrey Bolton, a Mayo Clinic administrator, flew from Rochester, Minnesota, to the Santee reservation in Nebraska. The Mayo Clinic was establishing an endowed scholarship for Native Americans who aspired to work in medicine, and Bolton wanted to apologize formally for the Mayo Clinic’s hurtful act in person on the reservation.

Bolton’s apology was widely covered in Nebraska and Minnesota news media, but I missed the story when it came out. The coverage was kind to the Mayo Clinic, generally pointing out that after the passage of a century and a half, it was trying to set things right. Stories of white apologies for the past are sometimes covered like this, it seems. Reporters and columnists celebrate the courage of those who apologize, recognize their bravery and their contrition, but they too often do so without delving into the violence and dispossession that provided the vital context for the particular act in question. That really bothers me.

We’re all apologies, but only for the fouls we commit in a game that you must know was rigged from the very beginning.

The execution of the Dakota 38 was an atrocity, no question. But it was not the only one committed before, during, and immediately after the Dakota “Uprising.”

By the end of the 1840s, most Dakota Sioux were destitute. The number of white settlers in Minnesota, which became a territory in 1849, continued to increase. Hard-pressed and impoverished, the Dakotas, under the leadership of Little Crow, signed treaties in 1851 at Mendota and Traverse des Sioux in which they gave up their claims to all their lands in Minnesota save for reservations along both sides of the Minnesota River north of New Ulm, and extending upriver for 140 miles.

The Dakotas signed the treaty in 1851 after accepting federal assurances that the cession would benefit them. They trusted their white father. The sale would provide them with the annuities they needed to purchase the necessities for survival in a tightening circle. But Federal officials viewed the treaty differently. They hoped to civilize and Christianize the Santees, to teach them the value of private property, and transform them into farmers on the white model. By reducing the amount of land they owned, and opening the ceded lands to white settlement, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea noted that the Dakotas would now “be surrounded by a cordon of auspicious influences to render labor respectable, to enlighten their ignorance, to conquer their prejudices.” Reservation life would bring preservation to the Dakotas.

The government established two federal agencies to oversee the civilization program, the Lower Sioux Agency at Redwood, and the Upper Sioux or Yellow River Agency. Some Dakotas accepted the changes proposed by their agents. Leaders like Wabasha, Wakute, and Mankato cut their hair. Others encouraged their followers to begin farming and living and dressing like their growing numbers of white neighbors. Yet these changes generated divisions. According to Big Eagle, those who “took a sensible course and began to live like white men” received special treatment from the agents. “The government built them houses, furnished them tools … and taught them to farm.” The “Blanket Indians,” or the “Long-Hairs” who rejected the benefits of American civilization, resented this special treatment. They objected to the pushiness and cultural arrogance of the agents and missionaries. As Big Eagle observed, “the whites were always trying to make the Indians give up their life and live like white men … and the Indians did not know how to do that, and did not want to anyway.” Too much change, Big Eagle said, called for in too short a period of time. Big Eagle and many other Dakotas resented the racism of white men who “always seemed to say by their manner when they saw an Indian, ‘I am much better than you,’” and he did not like that “some of the white men abused the Indian women in a certain way and disgraced them.”

Some warriors assaulted the farming Indians. Some may have shot at and poisoned Christian converts. Those who accepted the government program seemed to ignore many of their obligations to their neighbors. The houses built for farmer Indians had their own cellars that encouraged the hoarding, rather than the sharing, of food. The acceptance of Christianity signaled in part the abandonment of the teaching of Dakota shamans. The refusal to join warriors at the agent’s request signaled the declining authority of traditional leaders. The civilization program threatened in fundamental ways Dakota culture and community, and their world was out of balance.

Other sources of tension gripped the Dakotas. The white population of Minnesota continued to grow as large numbers of Germans and Scandinavians settled near the two agencies. Many Dakotas learned to hate the emigrants, who not only took their land and ran off their game, but refused to share what they had with hungry Indians. The Dakotas viewed them as intruders.

The settlers did not want Dakota hunters trooping across land that they felt was theirs, but the conduct of federal authorities at the agencies left them with little choice. Agents and other employees used their positions all too often for personal enrichment. They overcharged the government for goods and services that they provided to the Dakotas, and they claimed for themselves a share of the Dakotas’ annuities. They held much of the rest of the annuity money for payment of debts to traders. What’s more, in an effort to encourage Dakotas to embrace the civilization program, the agents withheld annuity payments to traditional Dakotas. Without food and money, the discontented left to search for game. They viewed the farmers and traders and agents as fundamental threats to their existence. They were very hungry. When Little Crow complained about the behavior of the traders, Andrew Myrick, one of their number, announced that “so far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung.” Astute observers recognized how dangerous the situation had become. The Episcopal Bishop for Minnesota, Henry B. Whipple, solemnly warned that “a nation which sowed robbery would reap a harvest of blood.” Nobody paid him much heed.

By the summer of 1862, the annuities still had not been paid. Four Dakotas rummaging for food killed several white settlers who confronted them near Acton, Minnesota. Rather than surrender the four warriors, the traditional Indians at the Redwood Agency resolved upon war. Before they struck, however, they sought the advice of Little Crow. He had participated in the government’s civilization program. He told the warriors that “the white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm. You may kill one—two—ten,” he said, “as many as the leaves in the forest yonder, and their brothers will not miss them.” However many you kill, ten times more will come to kill you. “Count your fingers all day long and white men with guns in their hands will come faster than you can count.”

He doubted that the Dakotas could prevail, but he reluctantly joined in the assaults. He feared the consequences of the earlier attack on the settlers, and he knew the demands for vengeance would be great. Best to take a stand now. On August 18, 1862, the Dakotas fell upon the Redwood Agency, killing two dozen agents and traders. The attacks thereafter became more general. Nearly 400 settlers died in the first few days of fighting. The Dakotas then attacked Fort Ridgely and New Ulm. The settlers drove back both attacks and from late August the Dakotas went on defense. Some called for opening negotiations with the federal authorities for peace. Light Face, a Sisseton, said that “he lived only by the white man and, for that reason, did not want to be an enemy of the white man; that he did not want the treaties that had been made to be destroyed.” Meanwhile, the federal forces converged on the Dakotas. Led by Colonel Henry Sibley, the American troops defeated a Dakota attack at Wood Lake in September.

Many of the Dakotas fled. Sibley convened a military tribunal to collect evidence against those who participated in the uprising. By November, he had condemned over 300 to death. As the condemned marched downriver, they faced the insults and anger of the frontier population. White settlers pelted the prisoners as they moved toward the place of execution. A white woman, one observer noted, rushed “up to one of the wagons and snatched a nursing babe from its mother’s breast and dashed it violently upon the ground.” The child died several hours later.

President Lincoln pardoned most of the condemned, many of whom, along with their families, had converted to Christianity while imprisoned. They had found some hope in the new religion. The President ordered them incarcerated at Davenport, Iowa. Thirty-eight others, Lincoln concluded, did deserve to die. His decision was unpopular in Minnesota. An editorial in the Winona Daily Republican thought that all 300 should die.

“It would be amusing, were the circumstances too solemn to be turned into a subject for ridicule, to point out the subtle distinctions which are thus made in the cases of these murderous barbarians—how one Indian is to be hanged by the neck until dead, because he fired the fatal shot which sent a defenceless white settler suddenly into eternity—how another is to be pardoned because he stood by approvingly until the shot had been sent on its mission of death, and then indulged his savage instincts by scalping the victim and horribly mutilating his dead body. The barbarian ravishers of women and the butcherers of infants are to be divided into two classes, guilty and innocent, upon the principle of nice metaphysical distinctions which turns over to execution one assassin where it directly applauds the conduct of ten others by pronouncing them worthy of again entering into society and running at large as the independent lords of a land laid desolate by their devilish deeds of outrage and blood.”

On the day after Christmas, they went to the gallows. As they waited for the trap to open, they sang their war songs and said their farewells to their families. It was the largest mass execution in American history. And it clearly wasn’t enough for many Minnesotans. The St. Cloud Democrat resented the in depth coverage of the executions, and the treatment received by the condemned. “The soldiers, reporters, officers and preachers, who shook hands with those demons, should each and every one wear his paw in a sling during the term of his natural life, or dip it into boiling lye and skin it.” The paper’s editorial writer continued:

“It makes one sick to think of the cunning, cowardly brutes thus lionized in sight and hearing of many of their surviving victims and in close neighborhood to the unburied bones of others, as they bleach in the wintry winds. Uncle Samuel’s soldiers are so busy feeding Indians, guarding Indians and shaking hands with Indians, that they have not had time to bury the neglected remains of their victims.”

White settlers killed by “miscreants,” “pigs,” and “wild beasts.” They were animals, and should be disposed of like the menace they were. If Minnesotans “do not shoot, or hang, or drown, or poison with wolf-bait, these erring misguided, unfortunate, wronged injured Siox [sic] hyenas they will deserve and receive the contempt of the civilized world.” White people in Minnesota “should kill them as they would crocodiles.” They were not worthy of the sympathy reporters showed them. “The sights and sounds of horror, the tales of death partings and hideous tortures brought into St. Paul by hundreds of survivors of the massacre of fifteen hundred whites has not occupied half the space in the St. Paul dailies which is consumed in the farewell grunts, dying hypocracies, and obscenities of thirty-eight of these demon-brute murderers.”

Little Crow escaped, but only for a time. He fled west, but returned later to the Minnesota valley. On July 3, 1863, a settler gunned him down as he picked berries near Hutchinson, Minnesota. His scalp was placed on display. The Dakota Sioux were driven out of Minnesota. Any Indian presence was too much for white Minnesotans in the aftermath of race war.

The New York Times 1619 Project has been in the news a good bit lately. Older historians, some of whom have not done much work at all in the history of slavery and the enslaved, have dismissed the enterprise. That older historians dismiss the work of their younger colleagues is nothing new, of course. It is the way that hey dismissed this important work that is troubling. They question the centrality of slavery in the formation of the American state and society. They see the institution of slavery as standing in contradiction to the nation’s founding principles.

As a scholar who studies Native American history, the opposition of these old-timers at elite institutions to their younger colleagues is baffling. They may still have power and influence, but no longer much by way of respect. Not any more. I look at the past and see a continent taken from native peoples, built on stolen lands, with labor seized from enslaved Africans and African-Americans. Dispossession and slavery, colonialism and racism: they rest at the black heart of the American story, from the arrival of Columbus to its Trumpian apocalypse. The founders, who too many people still revere as demi-gods, knew what they were doing and were open about it. True, they spoke occasionally of civilizing and assimilating native peoples, but that effort cannot be separated from the larger effort o acquire Indian lands and erase their culture. The Mayo Clinic has taken significant steps to address this repugnant part of its past, of its own history. This country has barely even started.

One thought on “Thoughts on the Dakota 38”