I remember many years ago at the American Historical Association Annual Meeting that the historian James Muldoon described Richard Hakluyt the Younger, who died four hundred years ago this past November, as the “Gene Roddenberry” of the Elizabethan age. It is an image I have used many times in my classes, even though few of my students know who I am talking about. Roddenberry wrote his teleplays for the “Star Trek” television series at the beginning of America’s space age. What would happen, so many of those scripts seemed to ask, when human beings began to encounter others? For Roddenberry, humans always prevailed despite their many idiosyncrasies, and demonstrated time and again their superiority over Vulcans, Romulans, Klingons, and a host of others the crew of the Enterprise encountered as it boldly ventured where no man had gone before. But the contact changed them. A little bit. Sometimes. But not always.

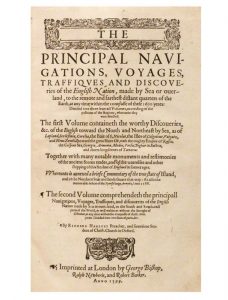

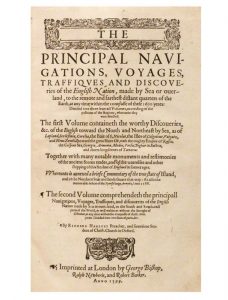

Hakluyt, too, seemed to wonder what would happen when English people left the confines of their island to go boldly in search of new worlds. For his Principall Navigations, a collection of English travel accounts totaling more than 1.7 million words in all, Hakluyt selected many stories of English adventurers encountering native peoples in South and North America, in Africa, Muscovy, Persia, and elsewhere. Oxford University Press will begin publishing next year a 14-volume edition of Hakluyt’s epic work. I am co-editing one of those volumes, with my particular focus being those documents that tell the story of Sir Walter Ralegh’s efforts to plant a settlement on American shores between 1584 and 1590. I have a small piece of the larger work, but the list of documents I an editing includes so real big-ticket items.

I am just back from a conference in Oxford commemorating Hakluyt’s life and casting a critical eye on his life’s work. Many of the presenters at this “Hakluyt@400” conference are editors of one or another of the projected fourteen volumes. From the papers presented, it was stunningly clear how much there is yet to learn from the Principall Navigations, and the enormous range of topics Hakluyt’s work illuminates. I have been thinking a great deal about the papers I listened to in Oxford, and I wish I had spent more time there. I learned a lot.

Many of the presenters at this “Hakluyt@400” conference are editors of one or another of the projected fourteen volumes. From the papers presented, it was stunningly clear how much there is yet to learn from the Principall Navigations, and the enormous range of topics Hakluyt’s work illuminates. I have been thinking a great deal about the papers I listened to in Oxford, and I wish I had spent more time there. I learned a lot.

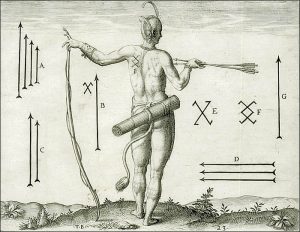

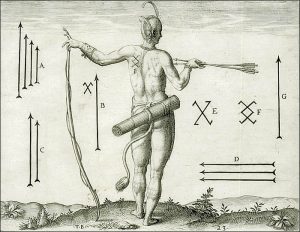

I was one of the few presenters who chose to talk less about Hakluyt than about some of the works included within the Principall Navigations, and some of the work Hakluyt helped publish elsewhere. I was most hung up by an engraving I have looked at so many times over the years. In the 1590 edition of Harriot’s Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, at the end of De Bry’s engravings depicting “the true pictures and fashions of the people of that part of America now called Virginia,” there appears this image, showing the “Markes of sundrye of the Chief mene of Virginia.”  From it, we learn that “the inhabitants of all that cuntrie for the most parte have marks rased on ther backs wherby yt may be knowen what Princes subjects they bee.” The mark of Wingina, “the cheefe lorde of Roanoke,” consisted of four vertical arrows, larger to smaller, left to right. Wingina’s sister’s husband’s followers, we are told, carried on their bodies a different mark. Two different marks belonged “unto diverse chefe lords in Secotam.” And Harriot associated three more marks with “certaine cheefe men of Pomeiooc, and Aquascogoc.” Clearly there were a lot of chief men on the Carolina Coast.

From it, we learn that “the inhabitants of all that cuntrie for the most parte have marks rased on ther backs wherby yt may be knowen what Princes subjects they bee.” The mark of Wingina, “the cheefe lorde of Roanoke,” consisted of four vertical arrows, larger to smaller, left to right. Wingina’s sister’s husband’s followers, we are told, carried on their bodies a different mark. Two different marks belonged “unto diverse chefe lords in Secotam.” And Harriot associated three more marks with “certaine cheefe men of Pomeiooc, and Aquascogoc.” Clearly there were a lot of chief men on the Carolina Coast.

You can see these tattoos, these raised marks, as well in John White’s painting of the dancing Indians.  It is hard to see in the version I inserted here, but go to the British Museum website, and you will see them. They are there, wearing the four arrows of Wingina. These tattoos, I would argue, as depicted by Harriot and White and DeBry, reflect an Algonquian political world, for lack of better terms, or social organization, at odds with what many historians of the region have described.

It is hard to see in the version I inserted here, but go to the British Museum website, and you will see them. They are there, wearing the four arrows of Wingina. These tattoos, I would argue, as depicted by Harriot and White and DeBry, reflect an Algonquian political world, for lack of better terms, or social organization, at odds with what many historians of the region have described.

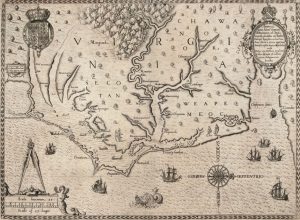

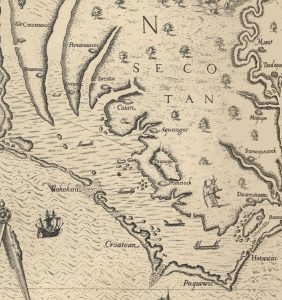

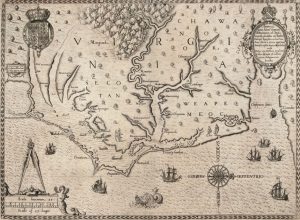

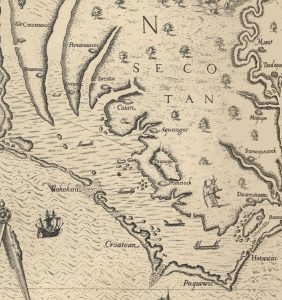

Another point: If you read much about early American history, you likely have stumbled across this map, also engraved by De Bry.  You are likely familiar with this image, too, one of the many hand-colored versions of the De Bry map.

You are likely familiar with this image, too, one of the many hand-colored versions of the De Bry map. We know little about the provenance of these maps, when they were colored, and by whom, but they are revealing to me nonetheless.

We know little about the provenance of these maps, when they were colored, and by whom, but they are revealing to me nonetheless.

Maps like these, quite simply, served purposes larger than the transmittal of geographic knowledge. Claims were made, arguments asserted, about possession and control of the new world. Maps like these expressed sovereignty, and English aspirations toward dominion and civility. Cartographic knowledge, in this sense, was subordinated to larger strategic and geopolitical concerns: control, incorporation, and the assimilation of lands, peoples, and resources into an Anglo-American, new world empire.

But more than that, DeBry inscribed a political geography that would have made sense to his audience. He acted upon European assumptions about how native peoples ordered their lives, how their communities functioned, and how they governed themselves. If Algonquian weroances, or town leaders, could be likened to European kings, then the lands upon which their communities stood could be understood as kingdoms, political entities with boundaries that could be measured, allegiance that could be acquired, and territory that could be controlled. DeBry, and of course the colorists who took his effort a giant step further, depicted the territories of Indian kingdoms because that is what they expected to see.

But the De Bry map, despite its considerable value, it seems to me has distorted the view of historians and anthropologists who have attempted to make sense of how the Algonquian communities of “Virginia” lived their lives and the nature of their relationships with the first English settlers on North American shores. David Beers Quinn, perhaps the greatest historian of early English maritime expansion and a scholar to whom anyone interested in Roanoke owes an enormous debt, and whose work in so many ways was ahead of its time, described the towns standing along the waterways of this region as belonging to one of several tribes, like the “Roanoke Tribe” or the “Secotan Tribe.” Lee Miller, in a quirky volume addressed to a popular audience, saw the weroance Wingina, so central to the story of Roanoke, as “the king of the entire Secotan country,” and a close ally with both “the Weapemeoc and Choanoac” tribes that together controlled the coastal plain. James Horn, who helpfully pointed out that these native communities were made up of “loose groupings of semi-autonomous peoples rather than centralized political entities controlled by powerful rulers,” nonetheless argued that Wingina was “Chief” of the Secotans, whose territory stretched from the Albemarle Sound to the Pamlico River, a tract that included many towns and villages. Wingina spent his time at his capital town, Secotan, but according to Horn also at the fortified town of Pomeiooc, and at the unfortified town of Dasemunkepeuc. Karen Kupperman and Seth Mallios, on the other hand, more plausibly saw Roanoke and Secotan as separate polities with a history of enmity between them. These are all very good scholars. But there is little consensus, and not all them can be right. So when we talk about these entities—Secotan, Choanoac, Weapemeoc—what, really, are we saying?

Here is what I think. We have been too careless in applying foreign, anachronistic, and inappropriate concepts to the study of indigenous peoples whose lived experience might be gleaned from the pages of Hakluyt’s Principall Navigations. The word “tribe,” after all, never appears in the Roanoke documents curated for us by Hakluyt, the word “chief” only as an adjective. The word “tribe,” indeed, was seldom used to describe native communities until the second quarter of the eighteenth century. The tribes etched by De Bry, in other words, seldom appear as meaningful entities in the surviving documentary record. By tracing the imagined course of these polities, by adding to and elaborating upon a map that reflected the biases and preconceptions of European observers, we risk imposing upon the region’s native peoples frameworks of social organization that I believe would have struck them as utterly foreign and wrong.

I am not alone, nor am I the first by any means to wrestle with these concepts. Anthropologists and archaeologists have long studied “tribes” and “tribalism,” and the formation and functions of “chiefdoms” of different levels of complexity and consolidation. Some have asked if the concept of a chiefdom is, indeed, a “sophisticated delusion” that keeps us from understanding what happened in early Native America.

Perhaps. Clearly some hierarchy and control and consolidation existed among Carolina Algonquians who greeted the colonists sent by Sir Walter Ralegh in the 1580s. Carolina Algonquian weroances may have occupied special houses. When Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe arrived at Roanoke Island in the summer of 1584 as the leaders of a reconnaissance voyage charged with scouting out the location for a future settlement, the women of the village carried the English voyagers into a house consisting of five rooms for bathing and a sumptuous feast. Weroances wore special attire, and signaled their status not only through body ornamentation and clothing, but also with posture and mannerisms. “In token of their authoritye, and honor,” Thomas Harriot wrote in one of the captions that accompanied De Bry’s engravings, weroances  “wear a chain of great pearles, or copper beades, or smoothe bones abowt their necks, and a plate of copper hinge upon a string.” Weroances married multiple wives, we know, because John White completed a portrait of “one of the wyves of Wyngyno.” And if English accounts are correct, the preferred treatment they received extended into the afterlife. Harriot described in detail the treatment of the bodies of dead weroances and the elaborate ceremonialism accompanying their storage in “the Tombe of their Werowans or Cheiff Lordes.”

“wear a chain of great pearles, or copper beades, or smoothe bones abowt their necks, and a plate of copper hinge upon a string.” Weroances married multiple wives, we know, because John White completed a portrait of “one of the wyves of Wyngyno.” And if English accounts are correct, the preferred treatment they received extended into the afterlife. Harriot described in detail the treatment of the bodies of dead weroances and the elaborate ceremonialism accompanying their storage in “the Tombe of their Werowans or Cheiff Lordes.”

Carolina Algonquian weroances conducted diplomacy. It was the weroance Granganimeo who traveled from Roanoke Island to greet the small reconnaissance party Ralegh sent to “Virginia” in the summer of 1584. Weroances oversaw the conduct of trade in their communities as well, activities that could cover an extensive geographic range. And within their communities, weroances oversaw the distribution of goods acquired through trade. When Arthur Barlowe, one of the two leaders of that reconnaissance voyage, attempted to trade directly with Granganimeo’s followers, he received a sharp rebuke from the weroance, who explained “that all things ought to be delivered unto him, and the rest were but his servants and followers.”

Weroances, as well, on occasion asserted their authority over neighboring villages. Archaeologist David Sutton Phelps asserted that eight chiefdoms (he called them “localities”) existed in the coastal Carolina region. Each locality he defined as “a geographic space within which there is a single political system . . . with a capital site and other sites ruled by sub-chiefs, in which material and other culture is closely shared.” What did this mean on the ground? It was a bit nebulous still, but Phelps’ formulation led the archaeologist Clay Swindell, for instance, to conjecture that “within the Secotan polity,” there “existed the small sub-chief towns of Pomeiooc, Aquascogoc, and Roanoke, each possessing small farmstead sites, temporary or seasonal sites in their catchment domain.” While Swindell is undoubtedly correct that advisers and religious specialists—priests and shamans—upheld a leader’s authority in each locality, much of what he writes is supposition, and we are not by these means any closer to understanding how Algonquian peoples organized their lives.

So, a first example: Carolina Algonquians first encountered English colonists in the summer of 1584, when the English reconnaissance voyage under the command of Amadas and Barlowe arrived at the Wococon Inlet. After several days spent exploring lands along the Outer Banks, Barlowe wrote, “there came unto us divers boats, and in one of them the kings brother, Granganimeo, accompanied with fortie or fiftie men.”

Granganimeo served as a surrogate for his brother, he claimed, because Wingina, the king to whom Barlowe had referred, had been “sore wounded, in a Fight which he had with the King of the next Countrey.” Barlowe famously described the New World in Edenic terms, with native peoples living in the manner of a “golden age,” and much has been made of this quote, but what most caught his eye was a world that had been ravaged by “very cruell, and bloodie” wars and “civill dessentions, which have happened of late yeeres amongst them,” conflicts that left the people he encountered “marvelously wasted” and in places “the Countrey left desolate,” and Granganimeo’s people clamoring to trade for English swords and steel.

Barlowe learned of a “King” called Piemacum, who ruled “a country called Ponuike.” Piemacum had allied with two other kings, one whose lands lay to his west, the other to his south, “uppon the side of a goodly River, called Neus.” Two years before the English arrived, Barlowe learned, “there was a peace made between the King Piemacum and the Lorde of Sequotan.” Despite this peace, “there remaineth a mortall malice in the Sequotanes, for many injuries done uppon them by this Piemacum.” Piemacum, for instance, invited “divers men, and thirtie women, . . .to their towne to a feaste, and when they were altogether merrie, and praying before their idol . . . the captaine or Lorde of the Town came suddenly upon them and slewe them every one, reserving the women, and children: and these two have often times since perswaded us to surprise Piemacum his Towne.”

They, Their, Them. The unclear references in this passage are maddening. The “Captaine or Lorde of the Towne” is not clearly identified, and who, precisely, were the “these two” who attempted to persuade the English to attack Piemacum? Granganimeo and Wingina? It is not completely clear. Were “Wingina, King of Wingandacoa” and the “Lorde of Sequotan” the same person? Some people think so. What does seem clear is that the world into which the English intruded in the summer of 1584 was fragmented and rife with tensions. We cannot be certain who we are talking about when we use accounts like this, but what we do see is that “tribal” names, like Secotan, do little to bring any clarity to a convoluted situation where towns engage in conflict with one another, and alliance with the well-armed and equipped newcomers seemed to offer an antidote to the ills they experienced.

A Second Example: The English returned to Roanoke in the summer of 1585, led at sea by Richard Grenville. They arrived at Wococon, and sent word “to Wingina at Roanocke”. That’s where he was. Grenville, however, almost immediately decided to explore the coast of the Carolina mainland in search of a more suitable site for settlement. The expedition’s flagship, after all, had run aground trying to enter the sound. His forty men, traveling in two boats, arrived at “the Town of Pomeioke” on the 12th of July. The weroance (perhaps Piemacum) welcomed the English. But why Pomeiooc? Was it part of a larger polity that included Wingina? Was it a “Secotan” town? An autonomous village? Grenville clearly sought a site for settlement superior to Roanoke Island. That the Algonquians at Pomeiooc welcomed his party suggests that they believed a close relationship with the newcomers could benefit them.

We know nothing more than that they visited the town, that John White had the means to do the work necessary to prepare for his paintings of the town and some of its people. The next day, the English party moved on. They arrived at a village called “Aquascococke” on the 13th. Two days later they arrived at Secotan, where they “were well intertayned there of the Savages.” They stayed one night. Most of the party then began the return trip to Wococon where they arrived on 18 July. One boat, however, returned “to Aquascococke to demaund of a silver cup which one of the Savages had stolen from us.” The English made their demand, and not receiving the cup, “we burnt, and spoyled their corne, and Towne, all the people being fledde.”

Think about this. The English had sailed through “Secotan” territory, according to this map, and attacked and burned an Algonquian town. No one from Dasemunkepeuc or Roanoac, the two towns we can unambiguously connect to Wingina, lifted a finger to help the people of Aquascogoc or avenge this act of violence. Nor did anyone from Secotan, or Pomeiooc, so far as we can tell. No retaliation. No complaint. Whatever ties of kinship or subordination or alliance, if they existed at all (and there is no evidence that they did) were not sufficient to precipitate a response to the English attack. We cannot be certain whether, or to what extent, Aquascogoc was part of a larger whole. Once again, autonomous towns. After this act of violence the English, with few other options, settled on Roanoke Island because that is where Wingina and Granganimeo wanted them to settle.

A Third Example. Weapemeoc. The 1585 colony was placed under the command of Ralph Lane after the departure of Grenville, and a good part of his confused and confusing account of his year at Roanoke, published in Hakluyt, was devoted to “the conspiracie of Pemisapan,” the former Wingina, “with the Savages of the mayne to have cut us off.” Harriot, of course, spoke of the “natural inhabitants” of the region in his account, but for the most part he spoke in generalities. “Their townes are but small,” he wrote. Some had a dozen houses, some a score, and “the greatest that we have seene have been but of 30 houses.” Some of these towns had palisades; others did not. In places, Harriot continued, “one onely towne belongeth to the government of a Wiroans or chiefe Lorde; in other some two or three, in some sixe, eight, & more.” The greatest weroance the English encountered—most likely the Choanoac weroance Menatonon—“had but eighteen townes in his government, and able to make not above seven or eight hundred fighting men at most.” Harriot said nothing more about how they organized their lives, nor about the relationships between these towns. So we are stuck with Lane, who went into such great detail at least in part to justify his decision to abandon Roanoke Island, his post, in June of 1586.

The 1585 colony was placed under the command of Ralph Lane after the departure of Grenville, and a good part of his confused and confusing account of his year at Roanoke, published in Hakluyt, was devoted to “the conspiracie of Pemisapan,” the former Wingina, “with the Savages of the mayne to have cut us off.” Harriot, of course, spoke of the “natural inhabitants” of the region in his account, but for the most part he spoke in generalities. “Their townes are but small,” he wrote. Some had a dozen houses, some a score, and “the greatest that we have seene have been but of 30 houses.” Some of these towns had palisades; others did not. In places, Harriot continued, “one onely towne belongeth to the government of a Wiroans or chiefe Lorde; in other some two or three, in some sixe, eight, & more.” The greatest weroance the English encountered—most likely the Choanoac weroance Menatonon—“had but eighteen townes in his government, and able to make not above seven or eight hundred fighting men at most.” Harriot said nothing more about how they organized their lives, nor about the relationships between these towns. So we are stuck with Lane, who went into such great detail at least in part to justify his decision to abandon Roanoke Island, his post, in June of 1586.

I’ve told this story in great detail in my book about the Roanoke colonies. Here I want to focus on one small part of the story. In the spring of 1586, Lane and his men began a journey into the interior, ascending the Albemarle Sound in search of an Algonquian conspiracy against the colonists. Only later, according to Lane, would the English learn that it was Pemisapan—Wingina—who was plotting against them, and not Menatonon, the weroance at Choanoac. Lane mentioned that the six towns he saw on the north shore of the sound—Pyshokonnok, “the womens Towne,” Chipanum, Weopomiok, Mucamunge, and Mattaque, all were “under the jurisdiction of the king of Weopomiok, called Okisco.” Six towns, one king. (White, too, depicted a cluster of towns on the northern shore of the sound which together he identified as Weapemeoc—four towns, one king).

Later, after tensions between Algonquians and colonists, natives and newcomers, had reached a critical point, and as Lane became convinced that Wingina was conspiring with Indians throughout the region to attack and kill all the English, this very same Okisco traveled to Roanoke and submitted himself to the English crown. So said Lane. But Okisco at this point apparently represented only his town. “Weopomiok,” Lane reported, “was divided into two parts”– at least–which raises significant questions about what we mean when we say “Weapemeoc.” The Weapemeocs, ruled by “King” Okisco, appear in the records as little more than an assortment of villages over which the weroance may have wielded some amount practical authority at some point in time. Indeed, Okisco entered into Lane’s story only at the urging of Menatonon, the leader of Choanoac, to whom he apparently owed some sort of allegiance. Towns may have come together in assemblages, collections of villages which may to our eyes have resembled tribes, but these alignments were so fluid, contingent and episodic, that it is difficult to use them as meaningful units of historical analysis.

The “Secotan,” meanwhile, as a group factored in Lane’s story hardly at all. He mentioned the name “Secotan” only once, Pomeiooc and Aquascogoc appear not at all. Autonomous towns. When John White, the artist and governor, returned to Roanoke in 1587, the year after Lane’s men attacked Dasemunkepeuc and murdered Wingina, and after Wingina’s remaining followers avenged their leader by wiping out a small holding party left on the island by Grenville in 1586 shortly after Lane’s departure, he sent messengers to “the weroances of Pomeioke, Aquascogoc, Secota, and Dasamunguepunke,” all separate polities in his view, to accept the friendship of the English.

It did not work out for White, and it worked out even less well for the colonists he left behind. He left Roanoke Island later in the summer of 1587, sent home by the colonists he ostensibly led to obtain additional supplies. By the time he returned three years later, the colonists had vanished. Whether they relocated to Croatoan, or moved fifty miles into the interior; whether they settled in the vicinity of Choanoac, Weapemeoc, or Chesepioc, their fate was almost certainly decided by one or more of the region’s many native communities.

So what? Well, we can look at these maps, and we can talk about “kingdoms” or “nations,” or tribes, but in doing so, we are speaking of constructs that are difficult to find in the documents selected for us and published by Richard Hakluyt the Younger.

The point I am trying to make—and, again, other historians have made this point looking at other locations where native peoples and newcomers encountered one another, is that we can best understand early America if we look past the tribes and nations inscribed on American shores by De Bry and look instead to the towns, to the most immediate local level: not at Secotan, Weapemeoc, and Choanoac as polities that asserted control over territories and peoples, as nations, tribes, and kingdoms, but as towns. White’s map, in this sense, might be more appropriate, a map that defined towns but not kingdoms, which emphasized the built environment of Carolina Algonquians more than the imagined chiefdoms of De Bry.

If we cast aside the concept of “tribes,” we certainly can arrive at a more nuanced understanding of the Algonquian world into which the English intruded beginning in 1584. But are there other implications? Have we too readily seen tribes, or imposed other European constructs, upon indigenous communities for whom they might not be appropriate or applicable?

Whether the fiercely autonomous communities of the Southwest upon whom Spanish authorities sought to impose new identities and definitions by congregating and collapsing them into more easily comprehensible “tribes”; or the Great Lakes Anishinaabe communities that French observers described as “nations” but that were, “in fact, extended family groups,” as Heidi Bohaker has argued, collections of kin, sharing “nindoodem” identity that transcended specific geographic spaces; or the towns of the Southeast that “might move or reconfigure themselves,” as Joseph Hall has pointed out, but that remained as the most meaningful center of Southeastern Indian life, historians have shown an increasing willingness to look to the local level to understand how native peoples organized their lives. Or think of the coast of southern New England, about which I have written. There we see towns that at one point are identified as belonging to the Pequot tribe, later to the Mohegans, or the Narragansetts, and later still the Niantics.

There is a large literature that examines the treatment of native peoples in Hakluyt and the pitfalls that come with an uncritical acceptance of his work as source material. Of course. But these remain texts of immense value, and by freeing ourselves from anachronistic concepts, we can come closer to a vision of England’s very early New World Empire that is not far from how Hakluyt himself saw it, one in which if English enterprises were to succeed, they would require the assistance of native peoples: to find wealth, to distill into the purged minds of the people the “swete and lively liquor of the Gospell,” and to “cut the combe” of the Spanish Antichrist, and in which these varied and autonomous towns possessed the power to determine the fate of these early colonizing ventures.

If we follow, then, the logic that informs the caption Harriot provided to De Bry’s engraving of the “Marckes of sundry of the Chief mene of Virginia,” then “Wingino, the cheefe lord of Roanoac,” and “Wingina his sisters husbande” and the “diverse chefe lords in Secotam,” and the “certaine chiefe men of Pomeiooc and Aquascogoc” were all distinct, all autonomous. The “tribes” are hard to find; towns remain at the center of things. Algonquian warriors, according to Harriot, and White, etched their loyalty to these village leaders into their bodies.

At the Hakluyt@400 Conference in Oxford, Mary Fuller of MIT noted with appreciation that a well-organized conference with well-selected presentations is a thing of beauty. The Principall Navigations is an immensely rich text, and as the papers presented at this conference showed, there is so much more that we can learn from the encounter between Europeans and others during this age of global encounters through a careful reading of Hakluyt’s gorgeous collection. I am still wrestling with these issues. If you are interested in what I have written here, and would like citations to back up what I have said, feel free to drop me a line.