The new semester begins next week. I spent a chunk of time this winter break updating the syllabus, making changes to the reading list, and what I hope will be successful adaptations to the new challenges teaching in the Post-Covid era presents. I am posting this in hopes that someone out there will find it of value or interest.

History 262 Indigenous Law and Public Policy Spring 2024

Professor: Michael Oberg

Meetings: MW, 8:30-10:10, Welles 225

Office Hours: MW, 12:30-1:30 Doty 208.

Contact: oberg@geneseo.edu

245-5730

Website: MichaelLeroyOberg.com

Required Readings:

Taiaiake Alfred, It’s All About the Land: Collected Talks and Interviews on Indigenous Resurgence, (2023).

Stuart Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, (2005)

Daniel Cobb, Say We Are Nations: Documents of Politics and Protest in Indigenous America since 1887, (2015).

Sarah Deer, The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America, (2015)

Luke Lassiter, Clyde Ellis, and Ralph Kotay, The Jesus Road: Kiowas, Christianity, and Indian Hymns, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002)

Readings online.

News Articles in online sources like indianz.com.

Court cases and documents as per syllabus.

Recommended Podcasts:

This Land, Seasons 1 and 2.

Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo.

Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s

Stolen: The Search for Jermaine

5-4: Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta

5-4: Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl

Recommended Movies and Television Shows

“Reservation Dogs,” 3 Seasons, HULU

“Little Bird,” 6 episodes, Amazon Prime

“Wind River,” Movie

“Killers of the Flower Moon.” (Movie)

“Frybread Face and Me” (Movie)

Course Description: This course will provide you with an overview of the concept of American Indian tribal sovereignty, nationhood, and the many ways in which discussions of sovereignty and right influence the status of American Indian nations. We will look at the historical development and evolution of the concept of sovereignty, the understandings of sovereignty held by native peoples, and how non-Indians have confronted assertions of sovereignty from native peoples. We will also examine current conditions in Native America, and look at the historical development of the challenges facing native peoples and native nations in the 21st century.

A Note on Grading: Your work this semester will consist of Participation, Journals, Quizzes, and a Final Paper.

1). Participation is much more than attendance. I view my courses fundamentally as extended conversations and these conversations can only succeed when each person pulls his or her share of the load. You should plan to show up for class with the reading not just “done” but understood; you should plan not just to “talk” but to engage critically and constructively with your classmates. Our conversations will depend on your thoughtful inquiry and respectful exchange. We are all here to learn, and I encourage you to join in the discussion with this in mind. Obviously, you must be present to participate. Please have all assigned readings available when we meet. The reading load in this course is quite heavy. It will challenge you to keep up. If you have trouble with the reading, please let me know. You obviously will be able to participate in classes with the most success when you complete the reading.

2). Journals: On seven occasions during the semester I will read your journals. I want you to think about what you are reading, and I want you to write about that experience. You will submit your journals on Brightspace. You should plan on writing a minimum of 300 words a week. DO NOT SUMMARIZE OUR CLASS DISCUSSIONS. DO NOT SUMMARIZE THE READINGS. I hope you will take this assignment as an opportunity to reflect upon what you are reading in class and in terms of current events, to discuss the things you wish that we had a chance to discuss in class, or to say what you wanted to say during one of our class meetings. Show me that you are thinking about the material we cover in our readings and in the classroom. Show me that you are keeping up with current events in Indian Country. Use the journals as an opportunity to educate yourself on issues in Native America that matter to you. Write each entry in the spirit of an essay, with a thesis and evidence to support your reasoning. For inspiration, you might read the news on INDIANZ.COM, National Native News, Native News Online, Indian Country Today, and CBC Indigenous for Canada, and the National Indigenous Times for Australia. In addition, I would like you to follow news on one Native Nation. You can set up a news alert on Google News, and stories will appear in your inbox whenever they occur. You can find a list of federally recognized Indian Nations here. Some Indigenous nations receive more coverage than others.

3). Quizzes: To assess the extent to which you all are keeping up with the readings, I will administer a brief quiz most class periods consisting of five questions.

4). Final Paper: Your paper should be approximately 15 pages in length. You will take the role of an adviser to a new President. Your assignment is to advise this President on Indian policy. In your paper you will do the following:

1). Identify what you see as a major problem or problems in Native America today that you believe the President should tackle during her or his administration.

2). Explain briefly the historical origins of this problem and how and why previous solutions have either failed to address it or ignored it entirely.

3. Offer a thoughtful, plausible, and realistic path towards solving this problem, and justify it legally and constitutionally.

4. Have at least 30 sources in a thorough bibliography that includes each of the following: news articles, government documents, reports from agencies working with indigenous peoples, and works by scholars who study these issues published in academic journals and books.

5. Format the paper according to the guidelines spelled out in the Turabian Manual. Write the paper with careful attention to grammar, style and substance.

With any of these assignments, I encourage you to visit with me during office hours if you have any questions. You should be clear on what I expect from you before you complete an assignment. The door is open. If you cannot make it to my office hours, please feel free to contact me by email and we will find another time. Many questions can be answered, and problems addressed more effectively in person during office hours than by email.

I will write extensive comments on your written work. I will ask you challenging questions, offer what I hope you will view as constructive criticism, and encourage you to push yourself as a writer and a thinker. But I will not give you grades, in the traditional sense, on this work. I want you to benefit from this course. On the date of our first class meeting, we will discuss the standards for the class. You and I will work together to arrive at a set of expectations for the sort of work that will earn a specific grade. In your final journal, and in individual meetings scheduled during Finals Week, we will discuss how well you think you did in meeting the agreed upon standards, and what your grade for the course ought to be. A proposed grading framework can be found, below.

A Note on Phones: I ask that all cellphones be stored during the entirety of our class meeting. If you expect an important call that just cannot wait, please inform me before class. Otherwise, I expect you to refrain from using your cellphone and I expect you to keep it out of sight. Please be present in mind and body. Much of the reading for this course will be online or available on Brightspace. You will need to bring your laptop to class, but I expect you to use it for class-related work only. Students who violate these policies will be asked to leave the class.

Discussion and Reading Schedule

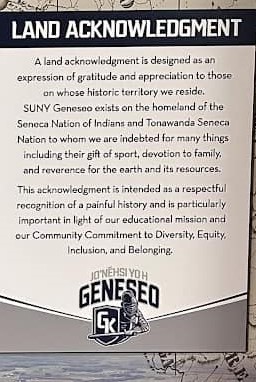

22 January Introduction to the Course: The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Reading: Banner, How, Introduction, Chapter 1; The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

24 January Native Nations in the United States

How to Read a Supreme Court Case

Reading: Articles of Confederation, Article IX; United States Constitution; Northwest Ordinance (1787); Federal Trade and Intercourse Act (1790); Treaty of Canandaigua (1794); Rights of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada; Banner, How, Chapters 1-3

29 January The Marshall Court and the Definition of Native Nations

Reading: Johnson v. McIntosh (1823); Banner, How, Chapters 4 and 5. If you are interested in a comparative perspective, I encourage you to look at Stuart Banner’s article, “Why Terra Nullius? Anthropology and Property Law in Early Australia,” Law and History Review, 23 (Spring 2005), 95-131, available on Brightspace.

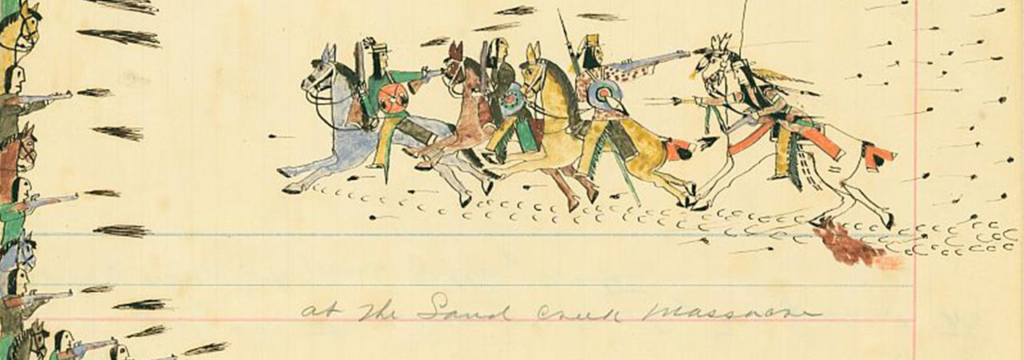

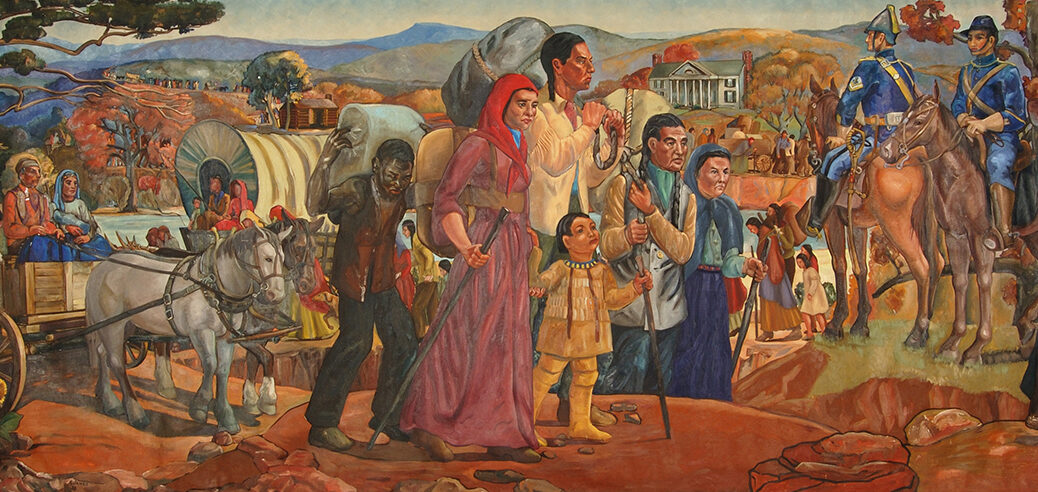

31 January The Expulsion Era

Reading: Documents on Jacksonian Indian policy (Brightspace); Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831); Samuel A. Worcester v. State of Georgia, (1832); Banner, How, Chapter 6.

Journal 1 Due.

5 February The Reservation System

Reading: Ex Parte Crow Dog; Major Crimes Act (1885) and US v. Kagama (1886); Banner, How, Chapter 7.

7 February The Policy of Allotment

Reading: Cobb, Nations, pp. 19-49; Banner, How, Chapter 8;Talton v. Mayes (1896); Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1903); United States v. Celestine (1909)

12 February The Indian New Deal

Reading: Reading: Cobb, Nations, pp. 54-93; Banner, How, (finish book) and the Indian Reorganization Act, 1934.

14 February The Termination Era

Reading: Cobb, Nations, pp. 97-106, 115-123; HCR 108; Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955).

Journal 2 Due

19 February Williams v. Lee and the Modern Era of American Indian Tribal Sovereignty

Reading: Williams v. Lee (1959); Native American Church v. Navajo Tribal Council (1959).

21 February The Era of Self-Determination

Reading: McClanahan v. Arizona Tax Commission, (1973); Morton v. Mancari (1974); Alfred, “Constitutional Recognition and Colonial Doublespeak;” “The Psychic Landscape of Contemporary Colonialism.”

26 February Red Power

Reading: Cobb, Nations, 124-188; Alfred, “On Being and Becoming Indigenous.”

28 February The Supreme Court’s 1978 Term, Congress and Tribal Sovereignty

Reading: US. v. Wheeler (1978); Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez (1978); Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978); Legislative Packet (Brightspace)

Journal 3 Due.

4 March The Power of Tribal Governments

Reading: Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe (1982); Duro v. Reina, (1990Atkinson Trading Company v. Shirley (2001); US v. Lara (2004)

6 March The War on Native American Children and Families

Reading: Margaret Jacobs, “Remembering the ‘Forgotten Child’: The American Indian Child Welfare Crisis of the 1960s and 1970s,” American Indian Quarterly 37 (Winter/Spring 2013), 136-159 (Brightspace); Brackeen v. Haaland (2023).

This would be a good time to listen to Season 2 of the “This Land” podcast hosted by Rebecca Nagel

Journal 4 Due

18 March Jurisdiction and Sovereignty in the 21st Century

Reading: McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020); Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, (2022). Listen to 5-4 Podcast episode on the Castro-Huerta decision.

20 March #MMIW #MMIWG

Reading: Watch this advertisement from the Native Women’s Wilderness, and this one from the United States Office of Justice Programs/Office for Victims of Crimes; Absorb as much of the following as you can: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls, (Seattle: Urban Indian Health Institute, 2017); a PBS NewsHour report featuring Abigail HenHawk, who oversaw the Urban Indian Health Institute report; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (Explore the website, read the summary of the 2019 Final Report); the report from the Trump Administration’s “Operation Lady Justice”; and President Biden’s Executive Order 14053 from November of 2021.

Search on Twitter using the hashtags #MMIW and #MMIWG. The podcast on the disappearance of Jermain Charlo would fit well here. Give it a listen, if you are able to find the time.

25 March Sexual Violence in Indian Country

Reading: Deer, Rape. We will discuss the book in its entirety. You will want to begin reading well in advance.

27 March Issues in American Indian Religion

Reading: Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990); Lyng v. Northwest Cemetery Protective Association (1988). Please watch on your own “The Silence,” a PBS documentary on one small Catholic Church in Alaska.

1 April Issues in American Indian Religion: Christianity in Indian Country

Reading: Lassiter, Ellis and Kotay, The Jesus Road, (entire book).

Journal 5 Due

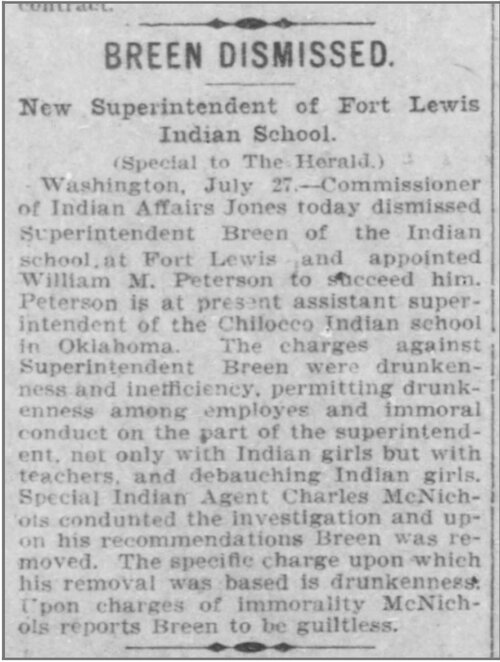

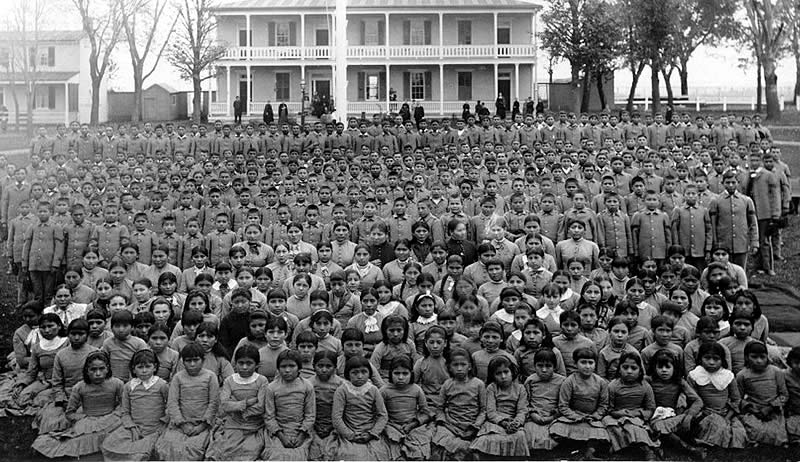

3 April Issues in American Indian Education: Boarding Schools and their Legacy

Reading: Gord Downie, “The Secret Path.” I would also like you to go to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School online project. You can find the website here. Your assignment is, first, to read Louise NoHeart’s student file (Brightspace) and then to read a minimum of at least 5 additional student files from the Indigenous Nation you have been following this semester (or a related Nation)(Ask for help if you are not clear on how to do this!) In general, for each student there is an information card and a student file. Read both of those and search for the student’s name in the newspapers and other documents. What do you learn about those students’ experiences at Carlisle? Be prepared to discuss what you found.

Please spend some time as well with the ArcGIS project from the University of Windsor looking at Canadian Residential Schools and this nine-minute report by Amy Goodman of Democracy Now!

8 April No Class—View the Eclipse.

Reading: “Come to Geneseo, Give Us Money, Look at the Sky.”

10 April Mascots and Other Forms of Appropriation

Audra Simpson, “Indigenous Identity Theft Must Stop,” Boston Globe, November 17, 2022; Darryl Leroux, “State Recognition and the Dangers of Race Shifting,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 46 (no. 2, 2023) (Brightspace).

15 April Economic Development and Poverty in Indian Country

Reading: California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (1987); National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC) website.

Journal 6 Due

17 April The Land and its Loss: The Consequences of Dispossession and Environmental Degradation

Reading: City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation (2005); Stephanie H. Barclay and Michalyn Steele, “Rethinking Protections for Indigenous Sacred Sites,” Harvard Law Review, (forthcoming, on Brightspace).

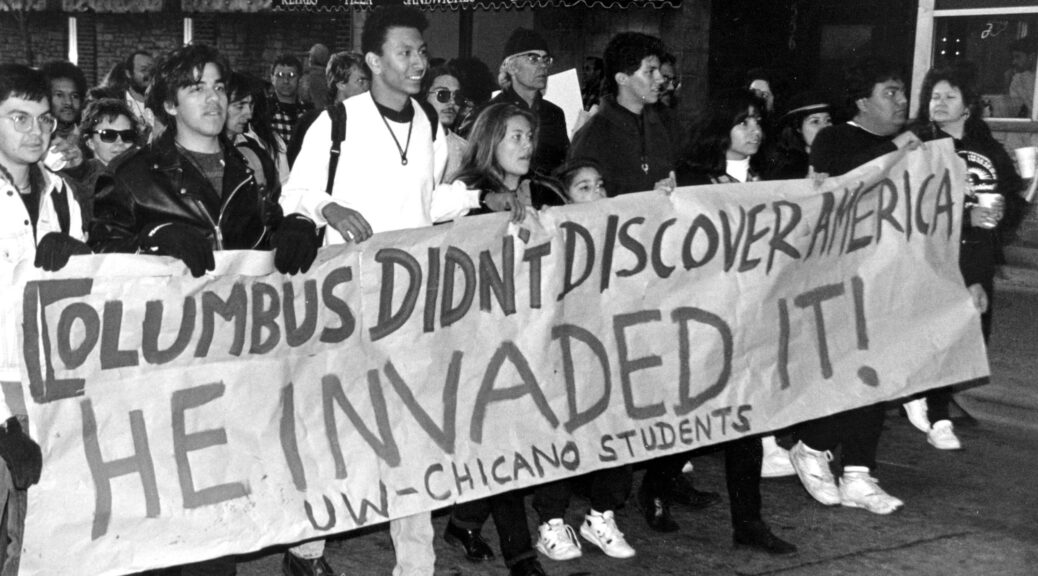

22 April Resistance: IDLA to Red Lives Matter, Idle No More

Reading: Watch Film: “You Are On Indian Land;” Cobb, Nations, 203-250; Lakota Law Project, Native Lives Matter; Jonah Raskin, “Red Lives Matter,” Tablet Magazine, October 10, 2021. You can also read my report about the death or Reynold High Pine in 1972; Jason Pero in Wisconsin and Colten Boushie in 2018; Please also look at the Idle No More website and read about this Canadian movement.

24 April GREAT DAY—NO CLASSES

29 April Health and Well-Being in Native America

Reading: Indian Health Service, “Disparities,” Updated October 2019; Linda Poon, “How ‘Indian Relocation’ Created a Public Health Crisis,” Citylab, 2 December 2019; Mohan B. Kumar and Michael Tjepkema, “Suicide Among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, 2011-2016),” Statistics Canada, 28 June 2019; Rural Tribal Health Overview, May 2022; Prabir Mandal and Jarett E. Raade, “Major Health Issues of American Indians,” 28 June 2018

1 May What Is To Be Done?

Reading: Alfred, “Reconciliation as Recolonization;” “From Red Power to Resurgence;” “You Can’t Decolonize Colonization”

Final Paper Due

6 May What is to be Done? (Continued)

Reading: Harold Napoleon, Yuuyarq: The Way of the Human Being, (Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Knowledge Network, 1996); Alfred, “Rooted Responsibility.”

Journal 7 Due

8 May Final Class Meeting

16 May Final Exam Period, 8:00-11:20: Individual Discussions to consider your final grade.

Learning Outcomes. This course fulfills the requirements for Diversity, Pluralism, and Power: Students understand (i) the diversity of identities that characterizes the United States; (ii) the ways in which systems of power lead to different outcomes for members of diverse groups; (iii) the reasoning and impact of one’s personal beliefs and actions; and (iv) how to participate effectively in pluralistic contexts (e.g., by communicating and collaborating across difference). It also fulfills the requirements for World Cultures and Values: Thus Students will strive to (i) understand systems of value and meaning as embodied in one or more cultures from different regions of the world; and (ii) assess interconnections among/across local and global systems and cultures. Courses in this category engage extensively with the past and/or present in cultures outside Europe and the United States (though they may also engage with content from cultures located within those regions, e.g., Native/Indigenous cultures).