The authorities in Yellowstone County quickly determined Reynold High Pine’s case of death. They found his body in the Burlington Northern Freight Yard on Billings’ south side early in the morning on May 14, 1972. County Coroner Leonard A. Larson concluded that the sixty-year-old man from Pine Ridge had stumbled into the path of a coming train around 6:30pm the evening before. Larson chose that time because it was then that the last train passed through the yard on those tracks before workers spotted the body at 4:30am. So certain was he that Larson felt no need for either an autopsy or an inquest. He did not even bother to draw a blood sample.

Native Americans in Billings did not think that Larson had things right. They suspected a cover-up, and they had good reason. Larson’s conclusions about High Pine’s time of death could not have been correct. Several witnesses saw High Pine at the Standard Bar on Minnesota Avenue, hours after the coroner said he died. These witnesses saw High Pine around midnight, in an altercation with Orville “Buzz” Jones, a 23-year old police officer who had just finished his shift at 11:00pm and was working, in uniform, as a bouncer at the bar. It just did not add up. High Pine was 5’3″, and 130 pounds. Jones had a full foot on him, seventy pounds, and a night stick which witnesses said he used.

T.R. Glenn, a Crow and the chairman of the Montana chapter of American Indian Movement (AIM) based at Eastern Montana College, said that “There is a conflict between the police version of what happened and the stories of the southside people who were witnesses.” Glenn and his associates–Ray Spang, a Northern Cheyenne, and a Winnebago named Frank LeMere–decided to visit Billings police chief Gerald T. Dunbar.

Glenn, Spang, and LeMere were upset. AIM as an organization was founded in the Twin Cities of Minnesota to monitor police brutality against the cities’ Native American population. HIgh Pine’s case looked and smelled like police brutality at a minimum, and the cover up of a murder at worst, especially because Dunbar denied that there had been any incident involving one of his officers.

They didn’t get far. Dunbar said that he would meet with “any group to hear a complaint if they acted rationally and didn’t shout.” The AIM activists did not meet Dunbar’s standard. He refused to meet with the “Long-Haired–until they acted decently and didn’t have a chip on their shoulder.” LeMere, who was in no mood to be told what sort of protest was proper and suitable for the chief of police, afterward said that “we simply exercised our right to protest inadequacies in police dealing regarding Indians. An Indian dies in Billings and everyone forgets–not even an autopsy was performed and this has got to change.” LeMere wondered how many more Indians would die.

Other Native Americans in Billings, not involved with AIM, were watching the conduct of the police. The 92 members of the moderate Billings American Indian Council joined the AIM activist in raising questions about High Pine’s death. Protests were scheduled and organized, with word of a march bringing in indigenous peoples from throughout North America.

This pressure forced Yellowstone County Attorney Harold Hanser to organize an inquest. He said his decision “was not prompted by Indian protest.” One of the jurors on the panel was a Crow, but the other four were white men, all familiar to the coroner. They concluded that the “probable cause” of High Pine’s death was being struck by a train, but they clearly had their doubts. They underlined the word “probable” in their report. None of the protesters were satisfied.

I do not know how Reynold High Pine died. But I question the coroner’s conclusions, and I bet you do, too. It is folly to pretend that historians do not live in the world of events. Though our craft emphasizes the importance of objectivity, it is never quite that simple. We read the work of scholars who preceded us. We work our way through the primary sources. We must do so honestly and fairly. We should not allow our biases and prejudices to color our interpretation of the sources we read. Few historians would disagree with these simple propositions.

Think about this story. I learned of Reynold High Pine because I saw an article in the important Native American newspaper Akwesasne Notes, which I had been reading because of its relevance to my research on the history of the Onondaga Nation. It was something that I stumbled across. Something about this story caught my eye. The reasons for this are not hard to imagine. I lived in Billings for four years, and I taught at Montana State University at Billings, formerly Eastern Montana College. I heard from more than a few Crow and Northern Cheyenne students I came to know about the rough treatment they received from the police and the county sheriff in Billings. But there is more to it than that. I read that story about High Pine in Akwesasne Notes the same day that the district attorney in Louisville, Kentucky, announced that the grand jury would indict none of the officers who gunned own Breonna Taylor in her own apartment. I read the article amidst the grief and frustration in Rochester, where I live now, that has surfaced since police videos became public showing officers strangling a troubled and naked African-American man on a winter night back in March. I attended some of the protests in downtown Rochester, just a couple of miles from where I live.

The point is that we historians, at the end of the day, seek answers to questions, and we set out to answer these questions in a systematic, thorough, and disciplined manner. These questions can come from many sources. It might be our sense that something is wrong in the prevailing interpretation of a historical event, and we want to know what really happened and why. But sometimes the events happening around us cause us to see something new in the sources–a connection, a parallel, or a line of inquiry–we might never have dreamed of otherwise.

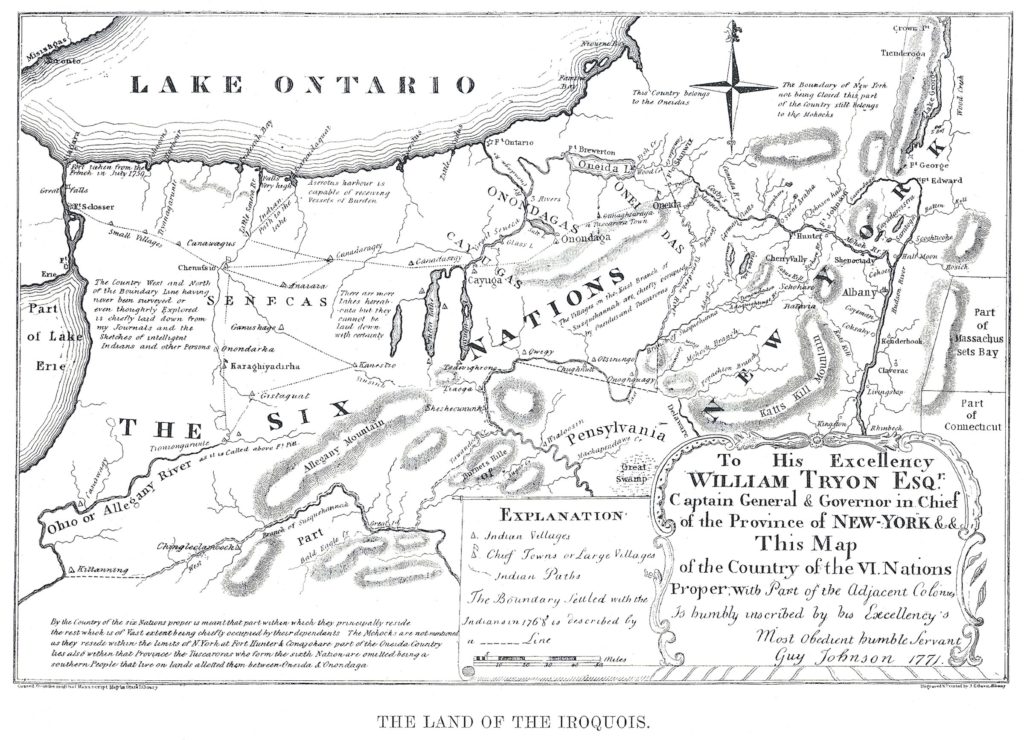

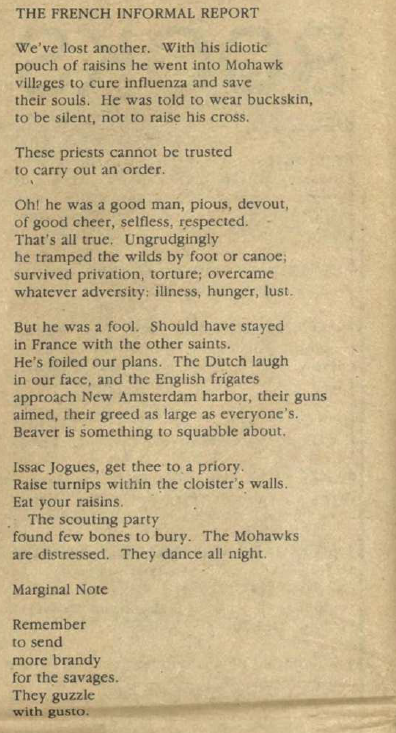

Black Lives Matter. We’ve been saying this since Ferguson, Missouri. Indigenous peoples, too, are killed in disproportionate numbers by law enforcement. This reality has bothered me for years, and I have written about it in a number of posts that have appeared on this blog. Reynold High Pine’s story shows us that the lives of Native peoples don’t mean much in cities and towns where they live on the margins, struggling to get by, coming and going, fucking up, falling apart, and too often getting beaten down. What is, always has been. White people have taken Native peoples’ lands and they’ve taken Native peoples’ lives. And in this country, historians will provide the only accounting of a problem that is as old as the encounter between natives and newcomers on these shores. and that may not be much of an accounting at all when so many Americans are so determined to hear nothing bad about their nation at all.